Armed with an astute sense of what constituted “soul” and built on a sturdy foundation of blues, country, and jazz, Booker T. & The MGs presented gutbucket dance music that brought teenagers to their feet. But more unlikely pop-music saviors could hardly be imagined.

They were an integrated band from the Deep South at a time when such relationships could prove fatal, providing the gritty Soulsville backdrop for smash singles from both Stax and Atlantic Records. They eschewed the sophisticated sounds emanating from Detroit’s Motown label for fatback party numbers typified by finger-poppin’ instrumentals such as “Green Onions” and “Hip-Hug-Her.” And they conquered America and Europe without singing a single note.

When asked what it was like to be part of the core unit at Stax Records, organist Booker T. Jones pauses for a long beat, then admits, “I didn’t pay a lot of attention to it at the time.”

It shouldn’t sound too surprising. After all, the Memphis native wandered into Stax when he was just 14 years old. He couldn’t have imagined the immensity of his musical future: joining forces with drummer Al Jackson Jr., guitarist Steve Cropper, and first bassist Lewis Steinberg, followed by Donald “Duck” Dunn, to back dozens of soul acts, ranging from Rufus Thomas and Otis Redding to Wilson Pickett and Sam & Dave, appearing with Redding at the ’67 Monterey Pop Festival, and touring Europe as part of the astonishing Stax-Volt Revue. And Jones didn’t slow down much when Stax dissolved in the mid-’70s — producing Willie Nelson’s finest Atlantic-era work, reuniting with the MGs to back Bob Dylan and Neil Young, winning a shelf-full of Grammys, and getting inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

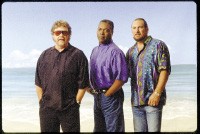

“I was there at the beginning, so I kind of took it for granted,” Jones says. “It was a place to belong, a place I wanted to belong to before I got in, when I was hanging out and listening to records at the Satellite Record Store.” Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Duck Dunn, Booker T. Jones, and Steve Cropper

“I’ve always described working at Stax like going to church every day,” says Cropper. “It was safe, and my energy level went up the minute I walked through the door. It was magic, although we didn’t know it at the time. We were just having fun.”

Fast-forward four decades to March 2007, when the MGs experienced that same thrill backing an all-star roster of Stax artists at Austin’s South By Southwest Music Festival (SXSW).

“When I was working with Willie Nelson, I used to come to Austin when there were just four clubs on Sixth Street,” says Jones. “Playing at Antone’s, where I used to hang out, was wonderful. My life is just getting full of moments like that.”

“We were back with Eddie [Floyd] and William [Bell]. I hadn’t been onstage with Isaac [Hayes] in years,” Cropper says. “I’d never done SXSW, but playing to a packed house, to people who knew our songs, was great. A lot of write-ups I saw later were overwhelmed by our performance, saying how good Eddie sounded and that William sounded like ‘a step back in time.’ It’s good to know we’re still capable!

“We’re able to adapt,” Cropper claims of the MGs’ ability to shift gears from a headlining instrumental group to agile backing musicians. “The way you have to address it is that Booker T. and the MGs are extremely highly trained session musicians. We could cover all the bases: If you wanted it to be jazz, it was jazz. If you wanted church, it was church. Even at Stax, there was a difference between the songs we did as the MGs and songs we did backing William Bell and Rufus Thomas.”

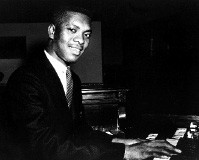

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Booker T. Jones

This adaptability has served the group well in the years since Stax disintegrated.

“Neil Young is incredible, just like Otis was incredible,” Dunn says. “They just play different styles. Neil’s a poet and he loves to rock, but he grew up on the same people I grew up on, singers like Jimmy Reed.

“It’s second nature,” Dunn says of the group’s onstage chemistry. “We’ve just been together for so long that what we really do is listen to each other. It’s spontaneous every time we play. We’ve got a certain tempo or a groove goin’ where anyone can venture off and go into something different. It’s fresh to us every night, and we never play it the same way twice.”

“I call it ad-libbing,” Cropper adds. “Duck and I have a little bit of a road map about where the changes are gonna go. In the old days, we just worked a song out then rolled the tape.”

The MGs have ad-libbed much of their career, after enduring numerous tragedies — including Redding’s death, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Jackson’s murder, and the bankruptcy of Stax — that would have felled other, lesser groups.

“We had a contract that wasn’t so great, but we were still a family — our routine was still the same,” Jones remembers of the beginning of the end, when Stax dissolved its distribution relationship with Atlantic Records (the deal cost Stax its back catalog of records that had been distributed by Atlantic) and briefly foundered before being purchased by Gulf & Western for $4.3 million in ’68. (Four years later, Stax would sign another deal, with CBS Records, that would ultimately sink the label in ’76.)

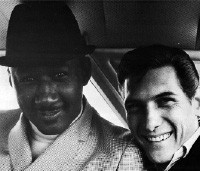

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Al Jackson and Steve Cropper

“The thing that happened at Stax was about the people and partly the place,” Jones says. “We all grew up within the history of blues and gospel down on Linden Avenue and Beale Street. We had the rockabilly and country roots of Cropper and Duck, and those combinations made the Memphis sound. You couldn’t re-create it anywhere else.

“But almost immediately, the studio was remodeled,” he recalls. “Offices were upgraded, and new people started coming in from New York and California. They built a new office right where Slim Jenkins’ joint used to be. It was a corporate environment, and they said we had to have three shifts, with the MGs working from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., the Bar-Kays working from 6 ’til 2 a.m., and another band coming in for that third shift. It reminded me of the steel mills.”

Even so, Dunn says, “Backing those guys and playing with Al made my life. I really didn’t have the answers ’til later on about exactly why it didn’t work out. Fortunately, we put it back together. I’m so glad we did.”

Invigorated by the SXSW experience, Jones says that he’s open to a discussion with the powers-that-be at Concord Music Group, which acquired the Stax name and the non-Atlantic portion of the catalog as part of its purchase of Fantasy Records two years ago.

“I see [the relaunch] as a positive thing, because the focus is on the music,” Jones says. “It could be a give-and-take thing that benefits both sides. Our music is getting played, and more people are becoming aware of it, like a revival or a resurgence of the Stax sound. The music always was our little gift to the world, and in return, we might get something else back from it. It’s a new life — 50 years is a long time.” Courtesy of Stax Museum

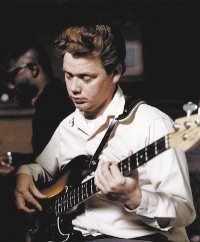

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Duck Dunn

For Dunn, however, the jury is still out. “I don’t know yet. I got a little bit bigger check this month,” he says of the royalties he receives for playing on countless hit singles — rates that haven’t been reconfigured in decades. “They’re still paying us on a rate for an album that cost $3.98 retail. It’s not fair. I haven’t been happy with it, but what can I do?”

“It’s water under the bridge to me,” Jones says. “I’ve had my troubles, and I still have to work, but I’d be working no matter how much money I have anyways. But [Dunn] has every right to feel that way. This country has dropped the ball on royalty laws.”

Musing over this year’s 50th anniversary of Stax Records, a celebration co-sponsored by Concord, Soulsville, and the Memphis Convention and Visitor’s Bureau, Jones says, “When I was there, Memphis was pretty much unaware of Stax and what it was doing. A lot of the city enjoyed the music and appreciated it, but we didn’t get wholehearted city support. The city has a rich, rich heritage that people are just now seeing.

“I am impressed with the [Stax] Museum, and I’m sort of flattered by it. I’m proud that there’s a music school there, because that was one of my main obstacles as a kid. It’s a great opportunity for local children and a really good use of the land.”

“Any time the Stax Museum, the label, and its artists can get extra publicity, it’s a good thing,” Cropper says of the anniversary celebration, which will bring the MGs and other Stax veterans to the Orpheum Theatre in June and to the Hollywood Bowl and the Sweet Soul Music Festival in Porretta Terme, Italy, later this summer.

Asked whether or not he’d work with Concord, Dunn concedes, “I’d be willing to sit down and talk about it. Us doing a record of Stax music with other artists like, say, Carlos Santana, is something to think about.

“I love to play live. That’s the reason most musicians play,” he says. “It’s just fun seeing people liking what you do. The first thing you want to hear is yourself on the radio — then you know you’ve made it. The second big thing for me was the Stax-Volt European tour we did in ’67. Getting inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the first ballot was great. So was the [2007] Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.”

“It’s pretty special,” Cropper agrees. “You can win a Grammy for a song, but this kinda thing is gonna be around for a long time. This is proof that you can digitize the MGs, run our music through a meat grinder, but that energy’s gonna stay in there.”