In 2007, Tom Shadyac fell off his bike. “I thought everything was fine, but within a few hours, everything wasn’t fine,” he recalls. “I couldn’t see in a room full of light because the light was too sharp. I couldn’t be in a room with sounds because sounds were torturous, whether it was a clanking plate or a car going by. I quickly knew something was wrong, and it wasn’t getting any better, it was getting worse. I looked it up online, and I checked every box of post-concussion syndrome.”

Shadyac spent the next three years recovering from his injury. “I’m a pretty athletic guy. I’ve had a number of concussions before. You only get so many concussion chips, then when your chips are out, you develop traumatic brain injury (TBI). And that’s what happened. I fell off my bike, and I’d had too many concussions. It wasn’t a terrible concussion, but it just never went away. I was sensitive to light and sound, I had to sleep in a closet. I had mood swings. I couldn’t engage in any kind of social life. It took a long, long time to heal. It’s one degree a day of a thousand degrees that have to be recalibrated.”

In 2007, Brian Banks got out of prison. Five years earlier, he had been an outstanding high school linebacker with scholarships on offer from the University of Southern California (USC) and a possible future in the NFL. When he got out, he was facing life as a felon and a registered sex offender.

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Brian Banks in the new film by Tom Shadyac. Sherri Shepherd plays his mother, Leomia.

Banks had proclaimed his innocence of the charge of rape a high school classmate brought against him. But he never got a chance to present a jury with his exculpatory DNA evidence or to challenge his accuser’s shifting story in court. The DA and his lawyer cooked up a plea bargain where Banks, who was facing more than 40 years in prison, pleaded no contest to a single charge in exchange for probation. The 16-year-old was given 10 minutes to decide his fate — and then, after he accepted the deal, the judge sent him to jail anyway. Faced with a bleak future of ankle monitors and menial jobs, he had little choice but to set out on an improbable quest to clear his name.

“I Couldn’t Picture Myself In A Suit And Tie”

Tom Shadyac’s first exposure to show business was from comedian Danny Thomas. “My dad [attorney Richard C. Shadyac Sr.] and he were good friends, and my father, of course, helped to found St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital,” he says. “But I saw what entertainment could do, especially for people like my mom. My mom was handicapped, and she had some issues with pain and spasms. She was paralyzed — a semi-paraplegic. We used to watch the Johnny Carson show together, and I saw how that lifted her up. I think that was sort of my rooting in the power of what entertainment, humor, and storytelling can do in a life.”

While in high school, in the mid-1970s, Shadyac started a joke-of-the-day series with a friend, and started writing short comedy skits for talent shows. He went to the University of Virginia with the stated intention of being a lawyer like his father, but says, “I couldn’t picture myself in a suit and tie for the rest of my life. So I took a shot at writing some humor.”

His first break came in the early 1980s, when his uncle introduced him to comedian Bob Hope. “While he wasn’t exactly my style — I was from a different generation — it was an opportunity to work with someone at the top of their field and to learn the building blocks of how to write a joke.”

Writing for the workaholic Hope was a comedic trial by fire. “It was kind of like being a doctor on call,” Shadyac says. “He would reach out at all hours of the day, any day of the week. He would say, ‘I’m at Walter Annenberg’s estate tonight, and the Queen of England is going to be there. Can you write me some jokes?’ Once, I was skiing with my friends on the weekend. I came off the mountain, and I wrote jokes.”

After writing for Hope for three years, Shadyac bounced around Hollywood until 1989. “I had tried nearly everything in show business,” he says. “I had written jokes, I had written sitcoms, I had written scripts. I had done some acting, I had done stand-up comedy, I had taught acting and improvisation. I decided to go back to film school to make a short film. I went to UCLA film school, and the first day of making my student film, I was squatting under a sink in the bathroom, doing the first shot of someone looking in a mirror. And it hit me — this is what I’m going to be doing the rest of my life.”

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

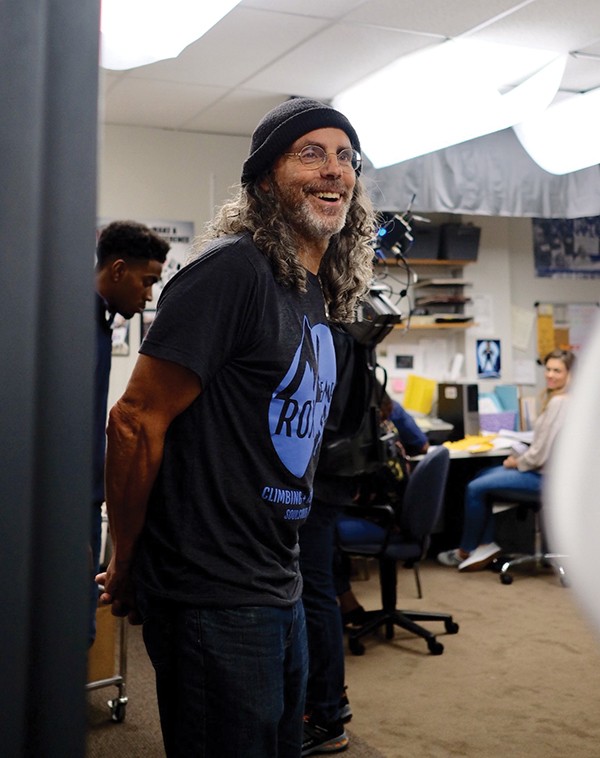

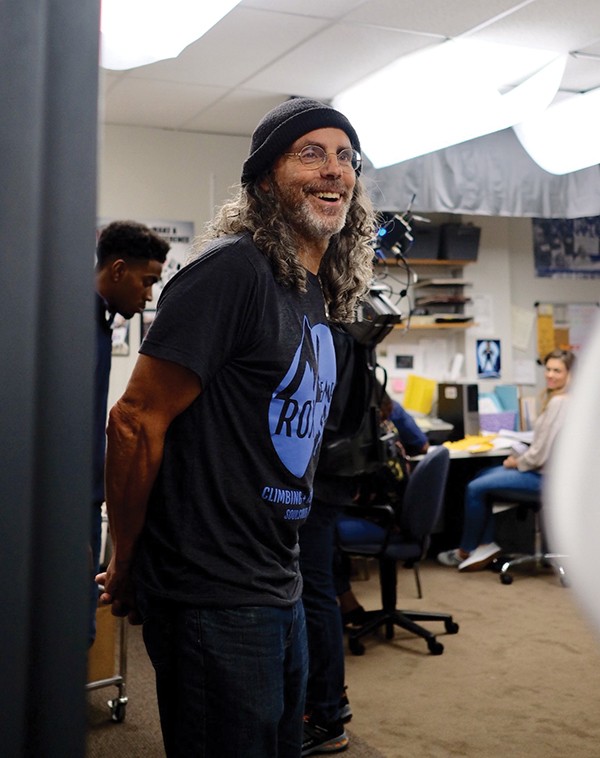

Director Tom Shadyac

Innocence Project

Brian Banks spent the first years of his post-prison life just trying to survive. His mother had sold their house and her car trying to finance his legal defense. He tried to get back into football, with limited success. His accuser had sued the Long Beach School District for creating an unsafe situation and won a $1.5 million settlement. Banks pursued rumors that his accuser had told her friends that he hadn’t raped her, but to no avail. He had made repeated appeals for help to the California Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization based in San Diego dedicated to overturning wrongful convictions, but since he had already served his sentence, they denied him assistance.

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Actor Aldis Hodge had to possess both the physicality and emotional depth to portray Brian Banks. “Aldis was that combination in one person,” says director Tom Shadyac.

A “Childlike” Filmmaker

In 1993, “I had gotten out of film school, and I was taking some meetings,” Shadyac says. “There was a script for Ace Ventura, but it was more of just an idea. It had some storytelling challenges, so I came up with a way to rewrite it.”

Shadyac had first seen a young comedian named Jim Carrey at The Comedy Store on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. He was a breakout star of the sketch comedy show In Living Color. “He was literally just this genius, bright light chewing up every scene he was in.”

Shadyac’s decision to cast Carrey would be a watershed moment in both of their lives — and in the annals of American film comedy. “Jim acted the movie out at the Hamburger Hamlet, a restaurant on the Sunset Strip,” Shadyac recalls. “I was there, and we put on a little show for the Morgan Creek executives, and they financed the movie.”

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective became a sleeper hit, earning $107 million at the box office on a $15 million budget. It made a superstar out of Carrey and put Shadyac on the Hollywood map. Shadyac would go on to work with Carrey again in 1997’s Liar Liar and 2003’s Bruce Almighty. “He’s got gifts and skills that I am in awe of — his intelligence, his specificity, his work ethic,” Shadyac says.

Shadyac’s skills with comedy talent didn’t go unnoticed by other actors. He made Patch Adams with Robin Williams and Evan Almighty with Steve Carell. In 1996, he directed Eddie Murphy in a remake of The Nutty Professor. “I think Eddie’s probably the most brilliant actor in the history of our business when it comes to becoming another character — creating a life, a specificity, a rhythm, an emotional history,” Shadyac says. “And he can do it on the spot.”

The director could have gone on making goofy (“I use the word ‘childlike,'” Shadyac says.) comedies indefinitely. But he was on the lookout for something different. “I always want to grow as an artist, so growth is its own challenge. I’ve tried not to repeat myself. Yes, there is a certain pressure that comes with success. Your last movie made this much money, so your next one needs to make more,” he says. “Success can breed stagnation. You stop listening. You feel your own power. You get less collaborative. For me, the challenge has always been, how do you keep those negative ideas at bay and try to grow as an artist?”

In 2002, he wrote and directed a drama called Dragonfly. “If you knew me, you would know that I’m not walking around yukking it up all the time,” he says. “I’ve got a spiritual side. I’m interested in what we call fate and God. What is this universal energy that puts the space and time drama in motion? Dragonfly was a way to express something different.”

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Exonerated

Brian Banks had been on probation for four years when something unexpected happened. He was contacted on Facebook by the woman who, almost a decade earlier, had accused him of rape. She wanted to meet up and talk to him. Banks was wary at first — meeting his accuser face to face would be a violation of his parole. But it turned out to be worth it. The accuser admitted to Banks that, fearing she would get into trouble after being discovered out of class, she had lied about the rape. Banks, with the assistance of a private detective, recorded the confession. Armed with new proof, he finally got the California Innocence Project to take his case. In May 2012, the DA who had convicted Banks moved to dismiss all charges against him and expunge his record. The next year, Banks signed with the Atlanta Falcons, becoming one of the oldest rookies in the history of the league.

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

The Road To Memphis

“The bike accident made me want to express other parts of myself,” says Shadyac. “I realized my time was limited. I was staring death in the face, and death is the great clarifier.”

After years of recovery, he directed the documentary I Am, which he calls “the most personal picture I have done.” He started a homeless shelter in Charlottesville, Virginia, sold his house, and moved into a trailer park in Malibu. He started teaching film at Pepperdine University until his brother, Richard Shadyac Jr., CEO of ALSAC, asked him to come to the University of Memphis.

“So I did, and it’s turned into seven years. I never left,” he says. “There’s a soul to this place. There’s a reason that soul came out of here, and rock-and-roll. There’s a soul to this place that’s deep and dark, bright and rich. It can get ahold of you … I came here to teach, and I ended up being the one who was taught. I learned about my students’ stories and what they face with such courage and perseverance. It inspired me and changed me.”

Shadyac bought property in Soulsville and opened Memphis Rox, which was the first climbing gym in Memphis. “It’s a safe space for kids from all over Memphis to recreate,” he says.

As he taught, he was still trying to get back in the director’s chair. “There’s this misconception that I took 10 years off,” he says. “But the past 10 or 11 years, I’ve faced more than my share of rejection. … It was all part of me needing to be reinvented as an artist.”

In 2016, while he was teaching at LeMoyne-Owen College, Shadyac was contacted by producer Amy Baer. “She met Brian Banks and thought his film had to be made,” he says. “It felt very much like the stories of my students, who had faced challenges with courage and positivity. Because of my experience in Memphis, I felt that I might have the credibility to tell this story. I certainly was passionate about social justice issues, and young people that I cared about had been facing so many injustices and doing it with positivity. I started to explore it and think about the possibilities.

“When I met Brian, it sealed the deal. Brian is such a unique, brilliant soul, who has faced the darkest possibilities that a society can impose on a person. He remained positive and came out of it shining like the sun. That light that Brian is changed me, and we hope that it will change others. They’ll see a part of America that they didn’t know existed, and they’ll also see the power of an individual who can meet a challenge with such persistence that it can change everything around them.”

In the film, Aldis Hodge plays Banks. “I didn’t pick him. He seized the role,” says Shadyac.”It’s a really difficult role. There’s a physicality to it, so that automatically eliminates about 90 percent of the actors. Brian was a linebacker and destined for the pros. You have to have that strength and physicality. You have to have that depth of experience and soul. Aldis was that impossible combination in one person.”

Brian Banks was shot here at Shadyac’s Memphis Mountaintop Media, a film campus he developed in Soulsville. “In L.A., the gates are closed,” he says. “Here, we’re keeping the gates open. We want to serve the community with our art, and we want the community to be part of that art. … I believe accessibility is important. The misunderstanding about the movie industry is that everyone is a writer/actor/producer. No. Cooking is an art form. You have to feed a crew of 150-200 people. Makeup is an art form. Hair is an art form. Construction is an art form. There’s this myriad of jobs available, and communities like South Memphis need jobs.”

LeMoyne-Owen College graduate Jeffrey Garrison was one of 30 young Memphians who interned on the Brian Banks set. “I shadowed the different departments and ended up staying with the camera department. I even took off work to be up there almost every day,” Garrison says. “That was the first time I was around people shooting films. Everything was new to me, everything was just breathtaking. … That was 2017. Ever since then, I have been working in the film industry. Right now, I’m an office production assistant for the TV show Bluff City Law. So I’m still in it, and I have aspirations of becoming a producer. There’s no turning back for me. I made my mind up.”

Justice For All

When Brian Banks premieres this weekend in Memphis and all over the country, it will be the culmination of a long journey. Banks and California Innocence Project attorney Justin Brooks (played in the film by Greg Kinnear) are co-executive producers of the film.

“I’ve screened a lot of movies in my day and have had a lot of strong reactions. This movie is about the strongest reaction I have ever had from a film,” says Shadyac. “I think it’s an important picture, especially for people who want to see a part of America that they’re not familiar with. There’s not yet a system of justice for all. I think it’s important to see the African-American experience, where the scales of justice are not weighted in their favor. They’re forced to take pleas and serve sentences that are not just. We all have to look at it and take responsibility for it.

“The reason I did this picture was that Brian reflected such positivity in the face of such darkness. It’s a metaphor for whatever we’re going through. Brian was put into prison physically, but we’re all dealing with some kind of prison in our own lives. Brian provides a role model to meet those challenges with light and courage and positivity. If he could get through what he got through, most of us could certainly get through what we’re going through.”

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street  Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street  Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street  Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street  Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street

Katherine Bomboy / Bleecker Street