The Midtown Memphis music scene has long been an incestuous network. It’s almost hard to find prominent musicians who haven’t worked together at one point or another. But one of the more interesting pairings in this world might be Robby Grant and Alicja Trout, who co-front the underrecognized indie-rock quintet Mouserocket.

Grant made his name on the local scene as the frontman for ’90s notables Big Ass Truck but has lately recorded most of his music via the somewhat-solo project Vending Machine, a home-recording-oriented “band” in which Grant tends to write quirky, dreamy songs about subjects such as his wife, kids, and home life.

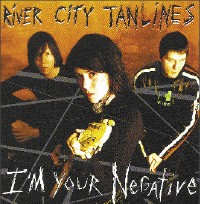

Trout became a major player on the local indie/punk scene via the synth-rockers the Clears and, later, as a co-conspirator (alongside Jay Reatard) in the ferocious Lost Sounds. More recently, Trout’s signal band has the blistering power trio River City Tanlines. In Mouserocket, Grant and Trout meet halfway: Trout tones it down, and Grant amps it up.

“The whole pretext for me was that I wanted to make a lot of noise and play guitar and not write songs,” Grant says. “I think Alicja turned to me one time at band practice and asked, ‘What song are you going to do?’ So it’s kind of morphed into that. But what I like to do in this band is play really loud guitar and sing really loud.”

Mouserocket started out, a decade ago, as a Trout side project of sorts — an outlet for lighter, poppier, more playful songs that didn’t fit her other projects. But it’s developed over the years into a classic, collaborative band.

“Here you can bring a skeleton of a song, or less, and make something,” Trout says. “Everyone can come up with a part. It takes a lot to get to that point, but it’s a true band. The sound isn’t determined by the songwriters.”

The band members who have coalesced around Trout and Grant include former Big Ass Truck drummer Robert Barnett, cellist Jonathan Kirkscey, and bassist Hermant Gupta. Barnett also plays with Grant in Vending Machine, and, in a Midtown landscape where there seems to be a handful of talented drummers who serve an entire scene, he stays busy, playing with Rob Jungklas, Hi Electric, and a jazz trio with guitarist Jim Duckworth and Jim Spake.

“He probably plays in more bands than any of us,” Grant says.

Kirkscey plays in the Memphis Symphony Orchestra but lately has been bringing his classical chops to the rock world. Gupta, alone among his fellow Mouserocketeers, is a one-band man.

With its members involved in so many projects, Mouserocket is not the type of band that practices regularly or lives together in a tour band. But everyone agrees that, with a familiarity born out of a decade together, the band thrives on its looser framework.

“We’ve gotten to the point where we don’t play a lot together, but we’ve played together for a long time,” says Grant. “We’re not a band that practices once a week and that practices our old songs. We can play shows and come together without that.”

“Our shows are boring if we practice too much,” Trout says.

This fruitfully ramshackle quality is reflected in the band’s new album, Pretty Loud, only its second official full-length release and one that was recorded over several years. It features new versions of several previously recorded songs — two from Mouserocket’s past (“Missing Teeth” and “Set on You,” previously poppy rock songs here gone electro and country, respectively), one from Vending Machine (“44 Times”), and one from Trout’s solo project Black Sunday (the epic “On the Way Downtown,” which richly deserves a second life).

Along the way, the album presents a sonic variety — especially in guitar sounds — perhaps unique among Grant’s and Trout’s myriad projects.

“That’s probably a result of it being recorded over such a long time in so many different places,” Grant says of the variety. “But I love that about it.”

“What are you supposed to do when you’re a songwriter and you record a song on a seven-inch that sells 300 copies or whatever and then you record a better version with a band that’s playing live?” Trout asks about reusing old songs, particularly “On the Way Downtown.” “Black Sunday is my solo thing, but if I’m playing [that song] live and the version is totally different, I think you have the license to record it again.”

If Mouserocket has, at times, been secondary to Grant’s and Trout’s other musical outlets, now the band seems to be moving to the forefront. As the father of two, Grant isn’t as free to tour (or as interested in touring) as he was in his Big Ass Truck days. Trout, the mother of a six-month-old girl, is in a similar place.

“For me, when I was in Lost Sounds, it was very stressful, and I needed this band to remind me that music was fun,” Trout says. “I’ve put it on the backburner because touring was taking up so much time. Now that I’m not touring … You know, having a kid has given me less time in some ways, but it’s given me more time to think about [my music].”