With Into the Woods, Stephen Sondheim takes audiences on a musical, psycho-sexual romp through the pages of Grimms’ Fairy Tales. The Sweeney Todd composer’s take on bedtime stories like Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella is less like an animated Disney musical than Hitchcock shocker. The irony is that when Into the Woods became a film, Disney made it. While Theatre Memphis’ lush, color-saturated production is not a copy of the film, it has a post-Disney feel.

Theater Memphis’ Into the Woods is nothing short of lovely, with lush storybook designs by Jack Yates complemented by Jeremy Allen Fisher’s even lusher lighting. Voices are strong, the orchestra sounds fantastic, and the acting is solid.

Renee Davis Brame may be the best wicked witch Memphis has seen to date, which is no small compliment considering how frequently the show is produced. Imagine Bette Davis eating Bernadette Peters to absorb her superpowers. She shares the stage with a strong ensemble that includes Lee Gilliland and Lynden Lewis as the Baker and his wife, and Cody Rutledge as a dimwitted giant-killer named Jack.

Jack Yates

Jack Yates

Old fairy tales get a little freaky in Into the Woods.

Into the Woods is relentlessly modern, putting it at odds with Theatre Memphis’ production,which is only intermittently so. The things that make the show so sumptuous dull the musical’s sharpest edges and un-sex it. What’s left remains gorgeous and exuberantly performed.

Into the Woods at Theatre Memphis through April 3rd

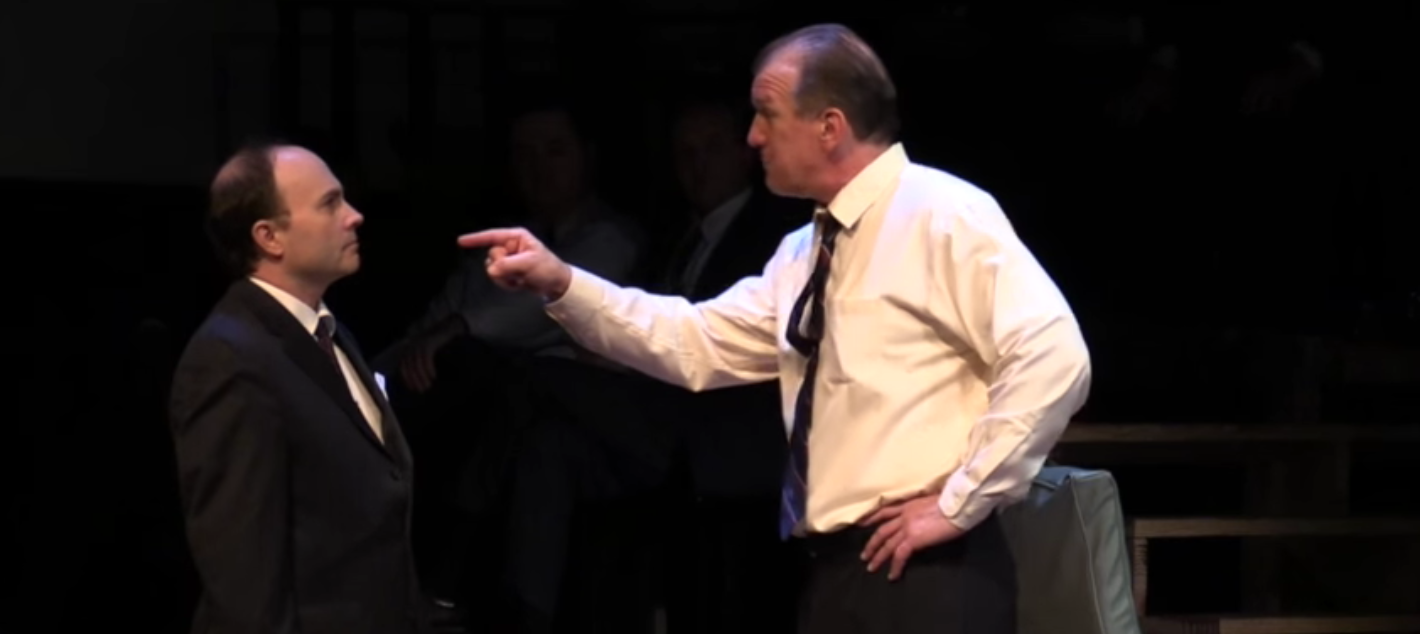

All the Way is an overstuffed sausage-grinding play about President Lyndon Johnson’s first 11 months in the White House. It begins with Kennedy’s assassination and ends with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill and LBJ’s election.

George Dudley is always a pleasure to watch on stage, and his LBJ is no exception. Curtis C. Jackson and John Maness stand out as NAACP leader Roy Wilkins and FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover. Greg Boller relishes his time inside the skin of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, and Michael Detroit makes a sympathetic, if never entirely convincing, Hubert Humphrey. The women of the ’60s are finely represented by Claire Kolheim, Irene Crist, and Kim Sanders. Unfortunately, this enormously scaled show requires more than acting.

All the Way should make us see that soldiers are blown up in boardrooms not on battlefields, and how even progressive politics can play out like a slow-motion lynching. It should make us flinch and look away often. It never does, but it’s an election year, which may put audiences in the mood for a three-hour reminder of the days when even an oil-funded politician as crude and bullying as Donald Trump could dream of a “more perfect union” and get elected.

All the Way at Playhouse on the Square through March 26th

Charles Smith’s Free Man of Color is a melodrama more relevant than well-told. It’s the story of a slave with uncommonly kind masters who, as a newly freed man, is given a chance to attend college. It’s also a story of 19th-century liberalism, and a man of learning who staked his reputation on the progressive belief that, with the proper education and rigorous training, exceptional Christian males of African descent might one day go back to Africa, conquer other brown people, and rule over them as God intended.

Although Free Man of Color is inspired by the true story of John Newton Templeton, who attended university in Ohio, Smith’s play is essentially a work of historical fiction. That doesn’t mean it’s not true.

Templeton, played with boundless decency by Bertram Williams, is invited to live with university president Robert Wilson, who treats his precocious student like a son when he’s not treating him like the Elephant Man. Wilson’s wife, played with chest-thumping authority by Kilby Yarbrough, Jane is a period-perfect hysteric, forever on the verge of going all “Yellow Wallpaper” in the absence of agency and purpose. She creates more context by voicing her concerns for Native Americans who are hunted like coyotes.

Michael Ewing is ramrod straight as Wilson, a self-enamored political animal with a gift for otherizing.

Free Man of Color wants more dynamic treatment but still succeeds in leaving audiences with plenty of food for thought.

Free Man of Color at the Hattiloo Theatre through April 3rd