I poke my head into my wife’s office and ask if she’s still interested in going to Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again with me. No, sorry. She would, but she’s not as far along with her work as she thought she would be at this point. But it’s okay. I can go on without her.

It’s just an ABBA movie. 114 minutes of ABBA. I can do this.

I arrive at the theater and the pleasant girl behind the counter waves me in. They know me here. I arrive at my seat after the Chevy commercial, but before the trailers are done. Things are looking up! What do I remember about the first one? Meryl Streep’s got a daughter who wants to know who her dad is. Turns out it could be Pierce Brosnan, the handsome rich architect; Colin Firth, the handsome rich banker; or Stellan Skarsgård, the handsome rich sailor. Everybody sings a bunch of ABBA songs and decides nobody cares who the father is because the real father was the friends we made along the way.

The film begins, and I’m reminded that Meryl Streep’s daughter Sophie is played by Amanda Seyfried, whom I believe is secretly a Mark II Emma Stone android. She immediately starts singing ABBA a capella. I take a deep breath and remind myself I’m only here because I couldn’t stomach The Equalizer 2.

Here we go again — more ABBA, more Greece, and more singing in the sequel to Mamma Mia.

Sophie is sending out invites to a grand re-opening of Hotel Bella Donna, and also her mom Donna is dead. Apparently we couldn’t afford Meryl for the 10-years-after sequel.

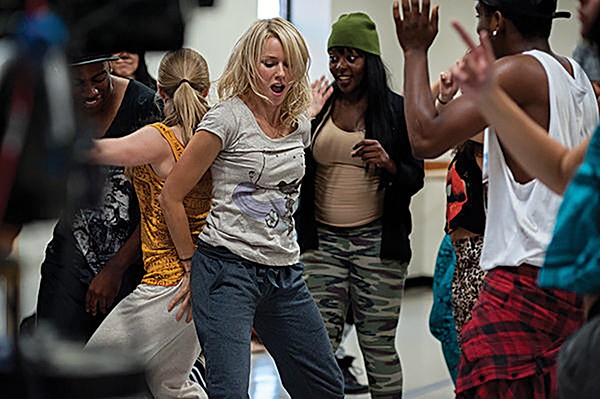

But what’s this? A flashback to 1979! Donna’s a Dancing Disco queen and also valedictorian. It takes me a minute to figure out the connection, because young Donna is played by Lily James, who doesn’t in any way resemble Meryl. In lieu of a valedictorian speech, Donna sings “When I Kissed the Teacher,” which I have to admit is thematically appropriate. Just so happens that I stumbled across a marathon of Leonard Bernstein’s Omnibus on Turner Classic Movies last night, and watched an episode where the great composer takes a deep dive into the history of American musical comedy. The form originated in the late 1860s when a theater troupe and a minstrel group were both stranded in a town with one theater, so they took turns performing scenes and songs. People ate it up.

The guy who wrote West Side Story would have despised this movie. Bernstein said the key to a good musical is that the songs must advance the plot and illuminate emotions, creating artistic unity. In Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, things just kind of happen to provide excuses to sing listlessly. These renditions are so flat and lifeless, they make the original versions sound raw and edgy. Even the subtitle, “Here We Go Again,” sounds drained of energy.

Everyone is very sad that Meryl is dead. I haven’t seen a production scramble to maintain its dignity after a losing its star since Charlton Heston played hardball with the producers of Beneath the Planet of the Apes. But they got the last laugh. He showed up at the end.

Did I mention the Hotel Bella Donna is on an island “at the far end of Greece”? That’s how Young Donna describes it as she sets out from Paris on her postgraduate transcontinental insemination spree. The first guy she meets is Young Colin Firth (Hugh Skinner). You can tell he’s a punk because he shops at Hot Topic in 1979. The Busby Berkeley-inspired production number of “Waterloo” he and Allen perform with a horde of French waiters dressed as Napoleon is pretty much the high point of the picture. Then it’s on to the ocean, where Donna ends up with Young Stellan Skarsgård, (Josh Dylan), on board his yacht The Panty Dropper. At least I think that’s what it’s called. I dozed off for a while. Finally, she meets Young Pierce Brosnan (Jeremy Irvine), and they cohabitate in a rustic farmhouse. In the barn is a powerful black stallion—which is in no way a sexual symbol—that Donna must tame.

The blonde guy’s obviously the father, by the way.

What’s weird is, in the ABBA Universe, the Greek economic crisis of 2009 still happened. And Cher is there, but she looks like Lady Gaga, and is absolutely murdering “Fernando.” Then, just as the film goes full Beneath the Planet of the Apes, it hits me: Donald Trump is not president in the ABBA universe. That’s why everything seems so aggressively pleasant.

This Greek island seems nice. I want to go there.