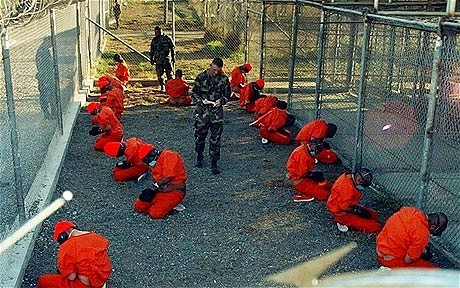

As President Obama works to secure his legacy, the Guantanamo quagmire all but guarantees that greatness and Obama will never be synonymous. As president, Obama has the ability to close down our Caribbean prison camp, — where currently 149 individuals reside — but he has refused to do so. Leaving Guantanamo open demonstrates the limits of President Obama’s political savvy, but more significantly, Guantanamo irreparably damages our democracy and dramatically shrinks our ability to lead internationally.

In 1903, the United States leased the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base as a way to protect U.S. economic interests on the island of Cuba and refuel naval ships. The U.S. essentially “took” Cuba in a brief 1898 war with Spain. We continue to lease this territory from Cuba, and the arrangement can only be terminated if both parties agree. Since the 1959 Cuban revolution, Cuba and the U.S. have agreed on virtually nothing, so Guantanamo remains contested. But like all U.S. military bases on foreign territory, no one disputes that the United States holds “complete jurisdiction” within the perimeters of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

According to the logic of the G.W. Bush administration — which opened the camp in early 2002 — “enemy combatants” (the term used by the Bush administration to classify detainees, which was dropped by President Obama in 2009) had no rights under international law. The U.S. Supreme Court challenged that view, and in a 2006 decision, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, declared that Article 3 of the Geneva Convention applies to all people, everywhere, at all times, including enemy combatants. Article 3

prohibits indefinite detention and torture and calls for access to fair trials.

The previous administration hoped to use on-site “military tribunals” to dispatch “justice” in Guantanamo, but, once again, they were stymied by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 2004 [Rasul v. Bush] that detainees had the right to challenge their detention in U.S. (civilian) courts.

President Obama, in early 2009, promised to shut down Guantanamo in a year, but politics intervened. Congress essentially defunded all efforts to transfer the detainees to the U.S. mainland, and many of the individuals held at the base have been renounced by their own nations. Thus, these detainees float in legal limbo, stuck on a contested U.S. naval base in the Caribbean while tenacious attorneys and frightened politicians determine their fates. Seven detainees have died in captivity, many have gone on hunger strikes, hoping to die as the world watches this national horror show with bitter derision.

So the United States has found a way to imprison people indefinitely, on U.S. territory, while suspending the most important notions of habeas corpus. This happened because we allowed it to happen. We don’t like to compare our nation to Argentina, but our practices at Guantanamo are very much analogous to the worst behaviors of the military junta in Argentina during the dark days of that nation’s Dirty War (1976-1983). Of course, when the Argentine generals were elected out of office in 1983 and relinquished power, the most egregious abuses ended. With the current “War on Terror” mentality firmly ingrained in American society, we’re dug in for permanent war, and evidently we’re comfortable as a nation with infinite detention of certain individuals.

Since 2002, Guantanamo has cost U.S. taxpayers roughly $4.7 billion. The real cost, though, is to our reputation abroad. We wonder about U.S. power eroding internationally; part of the uncomfortable answer is found in Guantanamo.

Keeping that prison camp open keeps us less free and less safe. It also threatens our democracy. We try to ignore our contradictions and legal sins while living in a dangerous, collective amnesia, but the rest of the world remembers.