Photographer Jamie Harmon beats the empty streets of a quarantined Memphis — keeping, of course, a good ten feet between himself and anyone he does happen to come across. On March 23rd, Mayor Jim Strickland announced the Safer at Home Initiative in response to the exponential spread of the novel coronavirus COVID-19, making official the soft quarantine many Memphians had already adopted.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Phil Darius Wallace and family

In the Bluff City, where gatherings are a way of life, taken for granted, Harmon, camera in hand, sets out to document the new normal. With his “Quarantine Portrait” series, he’s — with permission — peeking through windows, into Memphians’ lives, and capturing a slice of what life looks like under lockdown. The series is understandably somber at times, but the images resonate with an undeniable sense of hope. Perhaps paradoxically, there is something inherently community-minded in these photographs of isolated individuals. Many of these photos were taken before Mayor Strickland’s Safer at Home order went into effect, and long before Tennessee Governor Bill Lee or President Donald Trump even suggested that the current health crisis might, indeed, be more serious than originally forecasted. As such, the “Quarantine Portrait” showcases Memphians self-isolating in an act of solidarity — stepping up to fill the void of leadership with individual sacrifice.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

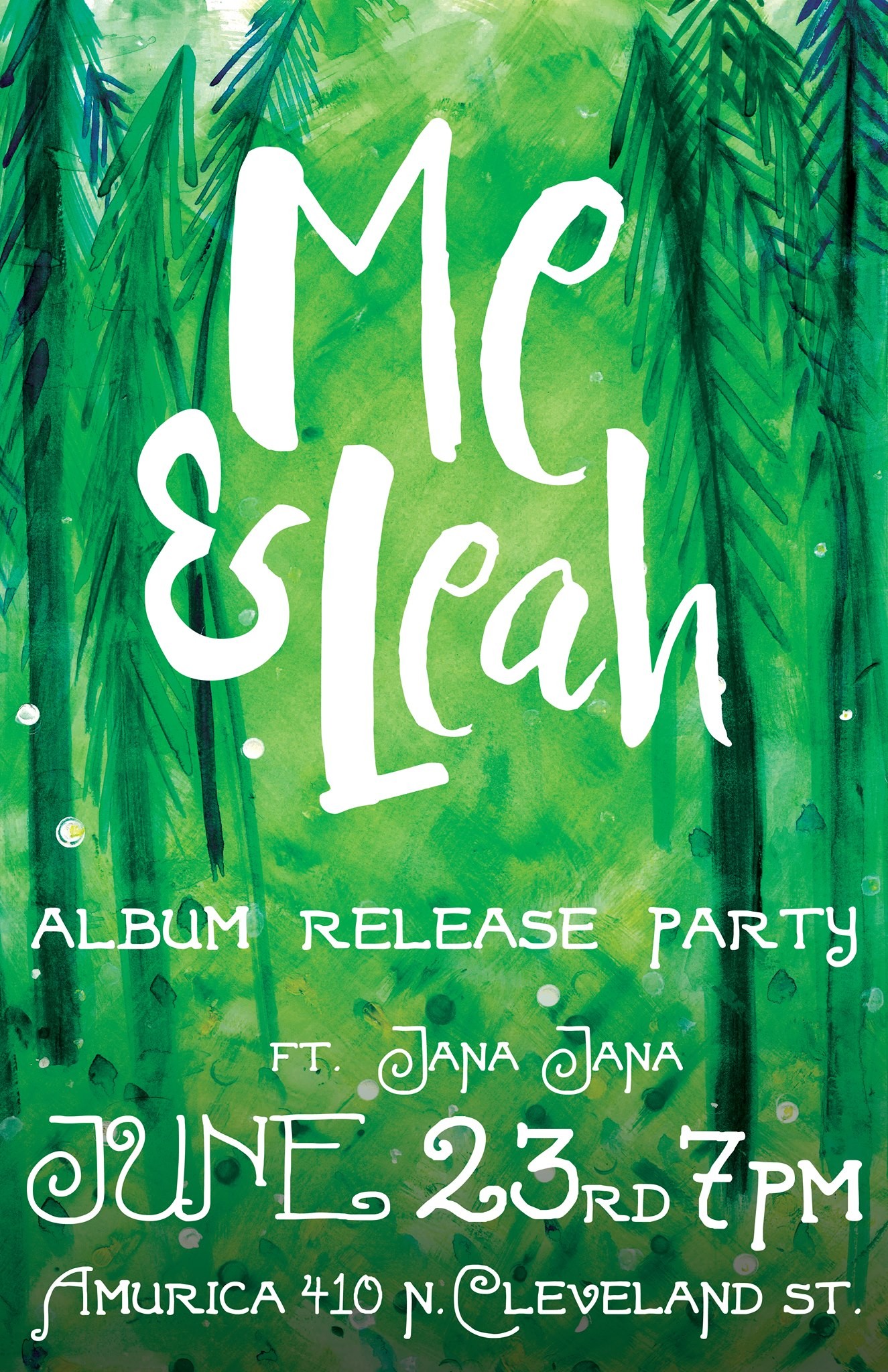

By day, Harmon is the owner/operator of Amurica Photo and the shared art manager at Crosstown Arts in Crosstown Concourse, the newly repurposed and remodeled Sears building.

“Because I was working 40 hours a week inside of a building, I was not as mobile as I wanted to be. I adapted something I could do where I was,” Harmon says of his “Complementary Objects” series, in which he juxtaposes, 1980s-style, a seemingly incongruous object floating ghost-like next to the smiling face of some Memphis personage. The series is lighthearted, goofy even, and Harmon’s 180-degree pivot to his series of self-isolated individuals speaks to his wide range as an artist.

“Luckily my kids are older. One thing I’m seeing is there are so many people stuck at home with younger kids or people with disabilities that had a routine. Now their routines are broken, and routines are pretty important to a lot of people. My routines have always been pretty adaptable or chaotic or whatever you want to call it. The routine of chaos is fine with me,” Harmon says.

The photographer hopes his brief visits to people’s homes can help break the oppressive monotony of a seemingly endless day, stretching on without distractions from the outside world. “The people who are sitting at home wondering what to do and maybe have little kids, this breaks that day up,” Harmon adds.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Karen Mulford, Oz, Alex da Ponte

“It’s hard to explain to a two-year-old ‘why’ and the concept of ‘temporary,’” says notable Memphis singer/songwriter Alex da Ponte, admitting that her son Oz’s struggles to comprehend the quarantine can be challenging. “He doesn’t understand why we suddenly can’t go to the zoo or go see his grandparents or play at the park,” da Ponte says. “It’s a big part of his world that is suddenly off limits. We bought a couple bags of sand and made him a sandbox with his kiddie pool in the backyard. Little things like that have helped.”

Doubtless, Harmon’s visit was a welcome distraction; Oz, who will turn three in June, can be seen hamming it up with a big smile in some photos in the series. In others, he is either dutifully ignoring the thin, bearded stranger with a mobile light setup and a telephoto lens, or is digging into the role of studious toddler, coached by his mothers, staring at an open coloring book.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Michael Weinberg, Robbie Johnson Weinberg, and kids

“We were empty nesters. We had two college kids come home and we’re living in a way we never thought we would again,” says Robbie Johnson Weinberg, the owner, creator, and longtime manager of Eclectic Eye. “We’re just living in this weird, unknown space.”

Weinberg says that, with uncertainties mounting — about her business and their employees, about her kids’ education and careers — the family has had to adapt. They’ve been creative, though, and have introduced a safe word into the family lexicon. Now, when talk of the nebulous future gets too dire, anyone can, with a shout of “cactus,” compel the family to change the subject and find a way out of prickly territory.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Georgene Boksich-Cachola, Sal Cachola

For Harmon, one of the most exciting aspects of the series has been the ideas his quarantined subjects bring to the venture. “In the past it’s like ‘No, you can’t get on the roof,’ and now, ‘If we’re ever going to get on the roof, this is the perfect time for it.’”

Indeed, the series documents people posing with their pets, clambering onto the roof, thrusting their arms through screen doors like zombies in a Romero movie.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Tamera and Ty Boyland

“It allows people to get out of that shell,” Harmon says. “It’s kind of nice that everybody feels like they gave something to it.”

“I think it’s truly just a gift in these weird times,” Weinberg says. “To have someone like Jamie come and remind us that we’re a family first is beyond lovely. There’s good stuff here, just in being together. The fear of isolation is almost paralyzing until you realize there’s some gift in the middle of it.”

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Catrina Guttery, Patrick Francis

“My mom was worried from the get go about being quarantined and not able to work, and I really thought she was just being paranoid. And now here we are,” says Alex da Ponte. “As of yesterday, I haven’t left the house for two weeks.” Da Ponte is hardly an outlier; to many, the new self-isolation precautions did seem like paranoia. Even as news from Italy and China drove home the severity of the problem, as the World Health Organization classified the coronavirus as a bona fide pandemic, America’s national, state, and local governments adopted different, often contradictory stances. For many, the uncertainty alone is enough to spark a spiral of worry and fear. No one seems sure when this will end — or what the world will look like when we emerge from our homes.

[pullquote-1]

“The rules have changed. You can’t go to restaurants. You can’t go to clubs or big parties, even outdoor festivals. All that’s off the table. So everyone’s walking around their neighborhoods,” Harmon says of the change he’s seen. “We walk around the neighborhood and we all talk to each other on our porches. It’s that funny ideal of America as how it used to be. Now, granted, how it used to be for people who had privilege. At times like this, there are probably people who are worried about losing their homes, not so worried about having a picture made.”

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Maritza Dávila-Irizarry, Jon W. Sparks

“No matter what we do, this is a collective experience,” Weinberg says, articulating the truth made apparent by this health crisis and Harmon’s series. COVID-19, coming in the wake of one of the most divisive moments in recent memory, and attacking without regard to age, party affiliation, or other arbitrary qualifiers, highlights simple truths: A community is only as strong as its most vulnerable members; the lines we draw to divide us often do far more harm than good. Harmon’s series makes that plain — the houses, duplexes, and apartment buildings represented are from various neighborhoods and income brackets. Harmon’s lens captures esteemed members of the community (Congressman Steve Cohen and Shelby County Commissioner Tami Sawyer, for starters) alongside now-out-of-work service industry folk. Straight, LGBTQ, black, white, Latinx, young, and old — all members of the Memphis community, all willing to sacrifice their own desires for mobility for the greater good.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Chris McCoy, Laura Jean Hocking

“People taking this seriously is absolutely a form of solidarity in our society. A lot of people who are staying home are doing so not because they think their bodies can’t handle the virus but because they are recognizing that it’s not about that,” da Ponte continues, admitting that she worries about her son’s grandparents staying safe. “I’m not worried about us, but we’re the carriers, and we have to watch out for our parents and our grandparents and our compromised friends,” Harmon says.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Billie Worley, Pat Mitchell

“Everyone’s adapting in their own way,” Harmon says. Da Ponte’s wife, Karen Mulford, adds, “I wonder if people will view social interactions in a new light. Will we hug and handshake with new appreciation? Or will we shy away from it, a lingering scar from this pandemic? I imagine people could go either way.”

[pullquote-2]

Perhaps this pandemic and our response to it will, like a fever burning off infection, help a nation infatuated with the ideal of rugged individualism accept that the world is interconnected, and only growing more so. After the cloud of coronavirus passes, whether we return with gusto to hugs and handshakes, or grasp a new greeting, there is hope that, however we greet each other, it will be with the warmth of family.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

Amurica.com

Amurica.com