Ashley B. Coffield is a 51-year-old public health professional who holds a master’s degree in public administration from Texas A&M University. The mother of two college-age sons taught public policy at her alma mater Rhodes College for nine years, helped create the Snowden School Foundation, and serves as a deacon at Idlewild Presbyterian Church. Sometimes, when she’s walking to her car after work, people call her a murderer.

As CEO of Planned Parenthood of Tennessee and North Mississippi, Coffield is on the front lines of one of the most consequential political battles of our time: the drive by conservative Christians and their Republican allies to overturn Roe v. Wade. Now that the Supreme Court seems poised to strip women of their constitutional right to safely obtain an abortion, Coffield and her allies are bracing for a return to the bad old days of limited reproductive rights — and perhaps worse.

“This is a human rights disaster,” Coffield says.

The Rise and Fall of Roe v. Wade

The debate over abortion rights in the United States is almost as old as the republic itself. In 1821, Connecticut passed the first law banning abortions in America. But juries would prove reluctant to convict women accused under such statutes, so the rare enforcement actions were usually taken against abortion providers. By the late 1960s, abortion on demand was available in five states and the District of Columbia. Women seeking abortions in the rest of the country either traveled to one of those states or resorted to less than legal means to end unwanted pregnancies. In some places, secret feminist organizations such as Chicago’s Jane Collective dodged police stings to provide safe and clean services. But for the most part, obtaining an abortion in the pre-Roe world meant paying exorbitant sums to back-alley practitioners, who may or may not have been doctors, and hoping for the best. In big cities, hospitals had entire wards devoted to treating women injured by unsafe abortion attempts.

“Abortion rights are important because it gets at the dignity of the individual and the autonomy of the individual to make decisions about their bodies and their lives,” Coffield says. “Without abortion rights, people are subject to the whims of fertilization and pregnancy.”

In 1973, the United States Supreme Court agreed by a vote of 7-2. Justice Harry Blackmun’s majority opinion found that precedents such as Griswold v. Connecticut, which legalized contraception, had established a right of privacy, and the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments extended that right to include a woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy.

But what many advocates thought would be the end of a long fight turned out to be just the beginning of a new phase. Abortion opponents who believe human life begins at conception, not at birth or at the quickening, organized a counter-offensive. They seized upon Roe’s framework that made first trimester abortion legal in all circumstances while allowing reasonable restrictions to protect the mother’s health in the second trimester onward to chip away at the right to abortion. “The most recent case, Planned Parenthood of Pennsylvania v. Casey, from the ’90s, is really the current statement of the law,” says Steve Mulroy, the Bredesen Professor of Law at the University of Memphis. That decision replaced Roe’s trimester-based framework with a standard based on fetal viability and allowed abortion restrictions as long as they don’t impose an “undue burden” on women seeking to exercise their reproductive rights.

Meanwhile, the Republican party discovered that abortion was an issue that allowed them to mobilize a large number of single-issue voters who could be counted on to show up at the polls. Ever since the Gallup organization began polling on abortion rights in 1975, a solid majority of voters have indicated they support abortion rights. In the most recent poll, conducted in 2021, 48 percent of respondents said abortion should be legal under certain circumstances, while 32 percent said abortion should be legal under all circumstances. Only 19 percent of respondents said abortions should be illegal in all circumstances.

Even though support for the Roe consensus of regulated abortion has hovered around 80 percent for decades, abortion opponents have been steadily gaining ground in state legislatures, including Tennessee’s, where anti-abortion Republicans now hold a veto-proof supermajority. “I think people have taken this right for granted, and sometimes it is just a matter of human nature, where you don’t realize what you’ve got until it’s gone,” says Francie Hunt, executive director of Tennessee Advocates for Planned Parenthood. “The vast majority of people are pro-choice, but that may not be a make-it-or-break-it issue that they are voting on. They may be voting on personality, or they may be voting on other factors. I kind of feel like, if you can’t trust me to make my own decisions about my own family, then you don’t deserve my vote.”

Coffield is blunt about the reproductive rights movements’ failures of the last 30 years. “We lost elections that were really critical to protecting our rights. That’s the bottom line: We lost. When Trump was elected, we knew we had four to six years left of Roe because of the opportunities he would have appointing justices to the Supreme Court.”

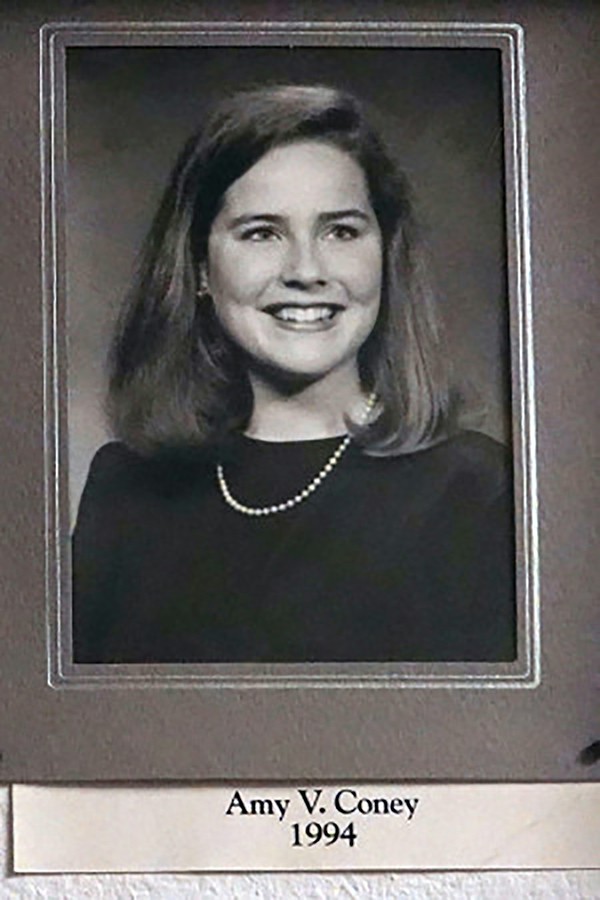

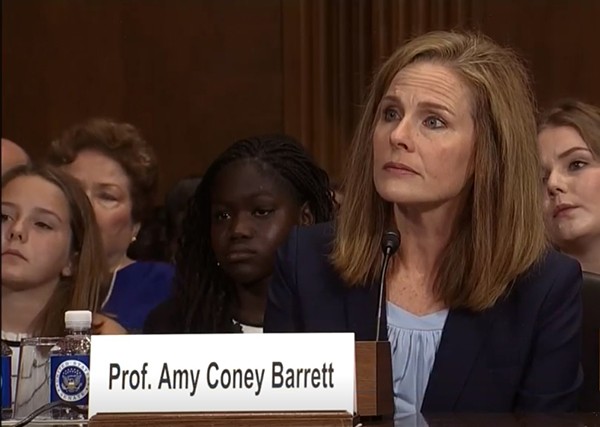

In February 2016 when Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell ignored 150 years of precedent by refusing to allow confirmation hearings for Democratic President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court. In 2017, McConnell shepherded the newly installed President Trump’s nominee Neil Gorsuch through the confirmation process. In 2018, Justice Anthony Kennedy, who had been the swing vote in favor of preserving abortion rights in the Casey decision, retired, and Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to replace him. On September 18, 2020, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a feminist icon who had long warned about the fragility of abortion rights, died 38 days before the election. On her deathbed, she told her granddaughter, “My fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed.” Instead, McConnell, who had held up Garland’s nomination for 10 months during the previous presidential election, sped the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett through in one month. Ironically, Barrett and Coffield are both Rhodes College alumnae, graduating only two years apart. “It’s Shakespearean,” says Coffield. “But also, it’s all the elections that our side hasn’t won at the state level.”

“I think there are at least three or four justices who, in prior opinions, have indicated a willingness to overturn Roe,” says Mulroy. “The new Trump appointees definitely seem particularly pro-life. So there’s a very good chance that Roe will be overturned.”

States of Confusion

As Republicans, buoyed by a hard core of anti-abortion voters who show up for low-turnout elections, took over more state legislatures, they have passed laws designed to test the limits of abortion rights by imposing ever more stringent restrictions, challenging the notion of what constitutes an “undue burden.” Two cases have emerged that could end universal abortion rights in America. The first is Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which concerns a 2018 Mississippi law banning all abortions after 15 weeks of gestation. Federal appeals courts have prevented the law, which violates the 24-week viability standard set by Roe and Casey, from taking effect. But last May, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the state’s appeal, leading observers to believe that the new 6-3 conservative majority is looking to overturn abortion law precedent.

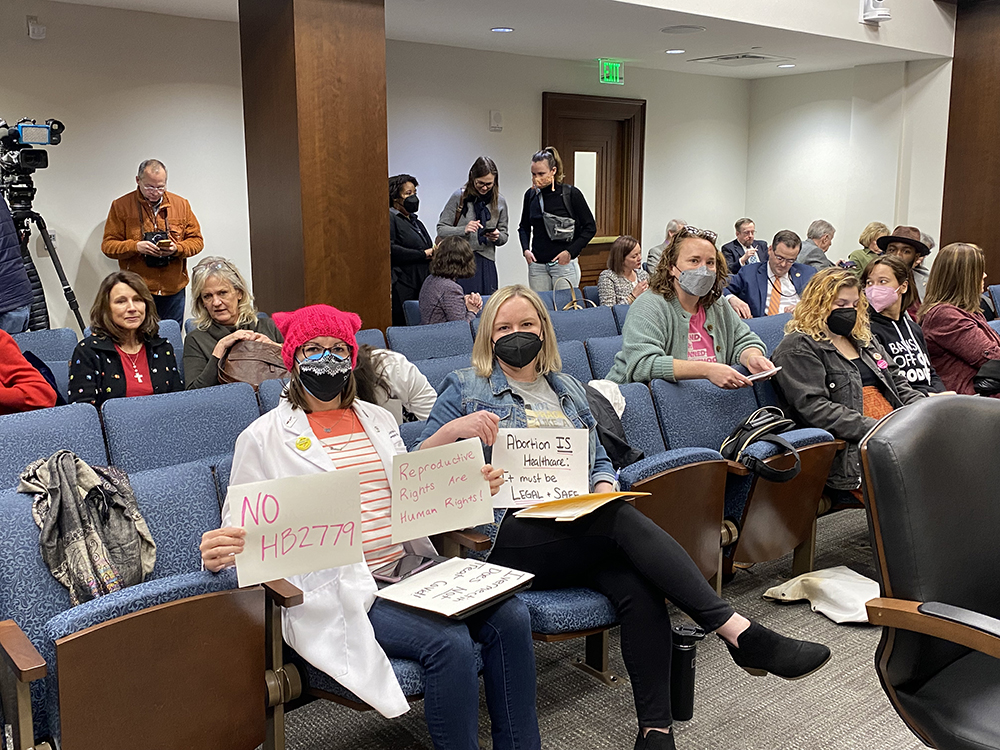

The second case is Texas SB 8, a law passed in May 2021 which bans abortions after six weeks, long before many women even know they’re pregnant. SB 8 and other copycat bills, including one recently introduced in Tennessee by state Rep. Rebecca Alexander (R-Jonesborough), provide a novel solution to the constitutional problems abortion opponents face. Instead of instructing law enforcement to arrest women and abortion providers, it allows private citizens to sue anyone who performs or facilitates an abortion for no less than $10,000 in damages, plus attorney’s fees and court costs. On March 15th, at a Tennessee State House Health Subcommittee hearing in Nashville, Alexander said, “While the Texas law prohibits abortion once medical professionals can detect cardiac activity, usually six weeks, the Tennessee language proposes to prohibit all abortion. Courts have blocked other states from imposing similar restrictions, but this law differs significantly because it leaves enforcement up to private citizens through civil lawsuits.”

When pressed at the hearing by state Rep. Bob Freeman (D-Nashville) as to whether or not her bill would allow anti-abortion activists to sue anyone attempting to help a pregnant rape victim who sought an abortion, Alexander responded, “My assumption is that they could because it says any citizen other than the rapist.”

Alexander did not respond to interview requests from the Memphis Flyer.

Mulroy says “abortion bounty laws” are “designed to basically prevent judicial review by making it difficult for a plaintiff trying to enforce abortion rights to find someone to sue. You could not sue the people who brought the lawsuit because they’re private citizens and they’re not representatives of the state. Then you could not sue the state because they are not the ones who are actually bringing the anti-abortion enforcement action. So it’s supposed to be sort of a loophole to prevent effective judicial review of a bill, which would restrict abortion rights in a way contrary to existing constitutional precedent.”

Mulroy thinks this “cynical ploy to delay judicial review” is ultimately doomed to fail because, eventually, a government official like a county court clerk will have to attempt to enforce a judgment, opening up an avenue for litigation. Last September, the United States Supreme Court declined an emergency motion to stop enforcement of the law while its constitutionality was still being litigated.

“It’s evolved very quickly because I would never have guessed that the U.S. Supreme Court would not have saved those women in Texas,” says Coffield.

Anti-Abortion Terrorism

On February 28, 2022, Republicans in the Senate filibustered the Women’s Health Protection Act, which would have enshrined the right to abortion in law. Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn (R) released a statement calling the bill, which had previously passed the House, “an attack against the health of women and unborn children. I voted against this legislation which would open the pathway for abortion on demand and legalize late-term abortions. The bill would make every state a late-term abortion state, force abortion drugs by mail, invalidate state laws to prevent coerced abortion, remove informed consent, and prevent states from stopping gruesome dismemberment abortion procedures.”

More recently, on March 20th, in a video questioning the judicial philosophies of Supreme Court nominee Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, Blackburn claims that Griswold v. Connecticut, which made birth control a protected right, is “constitutionally unsound.”

Such hyperbolic language is increasingly typical of abortion opponents, says Hunt. “I think Tennessee has grown much more ideological. It’s almost like they’re moving toward a theocracy.”

In the eight years Hunt has worked on Capitol Hill, she says, “a lot of the Democratic lawmakers have been good in terms of defending a pregnant person’s bodily autonomy and their right to make decisions over their own body. We’ve also seen several Republicans who themselves don’t really agree with their own party’s view on abortion. They might think that abortion is wrong, but they also think that it’s a private matter that needs to be left up to the family. But they are not going to cross their own party. And then we have what I would say is an unhealthy majority of folks in the legislature that are completely ideologically driven.”

Decades of increasingly hard-line rhetoric from the right has led to violent action on the ground. “We had our health center torched to the ground in Knoxville,” says Hunt. “We all felt, and I do believe, that’s a direct outcome from these political leaders who are absolutely extremist and have no moderation in how they talk about healthcare.”

There is a history of anti-abortion terrorism in the United States. In 1996, Christian Identity terrorist Eric Rudolph bombed the Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta, killing two and injuring 111 people. He went on to bomb abortion clinics in Atlanta and Birmingham, as well as a lesbian bar in Atlanta. At trial, Rudolph said his motivation for bombing the Olympics was to “confound, anger, and embarrass the Washington government in the eyes of the world for its abominable sanctioning of abortion on demand.” In 2009, Dr. George Tiller, who performed abortions, was murdered during a Sunday morning service in the Wichita, Kansas, Lutheran church where he was an usher. His killer, Scott Roeder, told the AP that he shot Tiller because “preborn children’s lives were in imminent danger.”

In January 2021, on the anniversary of Roe v. Wade, someone fired a shotgun through the front door of the Planned Parenthood health center in Knoxville. Coffield was just down the street when it happened. “That scared the hell out of us,” she says. “We had never had an act of violence at one of our facilities in Tennessee in all the years that we’ve been here, and we’ve been in Memphis since 1941. There was always a threat — our protestors have always felt threatening to us — but nobody had ever acted on it before.”

No one was arrested for the shooting. “Thus far, the suspect from that has not been identified despite the best efforts of investigators,” says Scott Erland, communications manager for the Knoxville Police Department.

On December 31, 2021, the Knoxville health center was destroyed in what was determined to be an act of arson. Knoxville Fire Department Assistant Chief Mark Wilbanks says that while “a considerable amount of evidence has been collected from the scene,” no new information about the crime has been uncovered. “There have not been any arrests at this time, and I do not have any suspect information.”

“I’m still processing that our actual health center burned down,” says Coffield. “I still wake up in the morning and think that it’s there and that we’re gonna be seeing patients there today. I have to remind myself that it’s gone and that our patients don’t have anywhere to go.”

What the Future Holds

“I think so many people have had positive experiences with abortion,” says Coffield. “It’s been a lifesaver for so many people — for somebody that you know — and it will continue to be a necessary part of healthcare.”

The immediate future of abortion rights in Tennessee is “gloomy,” Coffield says. “When we heard oral arguments around the Mississippi case, it was discouraging. We didn’t see any bright signs there that [the Supreme Court] are not going to significantly curtail, if not overturn Roe altogether. So we have to prepare for the worst because we have patients who are still gonna need services.”

The court’s decision could come as early as June. “Our legislature has already decided to ban abortion,” says Coffield. “We have a trigger law, which, if Roe is overturned, means abortion is illegal with no exceptions within 30 days.”

Women needing abortions would be forced to travel out of state. “In the west end of Tennessee, unfortunately, the only place that people have to go that’s in driving distance will probably be Illinois,” Coffield says.

Four generations of women who have grown up taking reproductive rights for granted are in for a rude awakening, says Coffield. “They’re going to have fewer options to control their fertility and pregnancy. It’s going to cost them more to get the services that they need. They’re going to need to be vigilant about avoiding pregnancy. If they are pregnant, they’re going to have to know early and they’re going to have to reach out to Planned Parenthood and other providers to get all of their options as quickly as possible. We’ve talked about emphasizing some of the services we have like emergency contraception and making sure people have that available to them at all times. It needs to be in your medicine cabinet. We need to reemphasize effective forms of birth control and compliance with birth control. We need to emphasize that you need to have a pregnancy test at home and ready at all times so that you can find out as early as possible if you’re pregnant.”

If the Supreme Court cuts so deeply into the right of privacy that it invalidates Griswold v. Connecticut, extremists could go even further. “Their lack of respect for people’s individual rights and to their right to comprehensive reproductive healthcare doesn’t bode well for birth control,” says Coffield.

Planned Parenthood will continue the fight. “Our plan is to dig into organizing. We have three pillars to our mission, which is education, advocacy, and healthcare. The education and advocacy components won’t go away. Those are going to be more important than ever because we’re not gonna be able to turn around this human rights disaster without education and organizing. … Planned Parenthood is not going anywhere. We are going to turn this around. It’s just gonna take a long time — and we can’t do it alone.”

Wikipedia: CSPAN

Wikipedia: CSPAN