“Don’t pay any attention to what they write about you.

Just measure it in inches.” — Andy Warhol

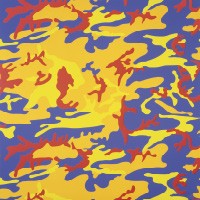

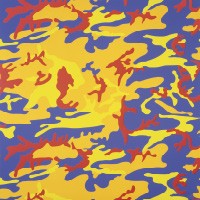

David McCarthy stands in the downstairs gallery at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, nodding sympathetically at a wall full of oddly colored camouflage prints like a police psychic attempting to mentally bond with an object once touched by a murder victim.

“It’s hysterical,” he concludes, snickering a bit. While others might look at the wall and see only a bunch of crazy colored camo, McCarthy, an art history professor at Rhodes College, husband of Marina Pacini, the Brooks’ chief curator, and the author of Pop Art, a concise, generously illustrated tour through the Warhol era, sees another perfect example of the catty artist’s deadpan wit.

“This was also a way for Warhol to approach abstract expressionism,” McCarthy adds, which is a polite way of suggesting that Warhol’s outlandishly imagined camo samples aren’t merely outlandishly colored camo samples. They are also a shout-out to 1980s hip-hop culture and a dig at the self-absorbed romanticism of mid-century art stars such as Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, neither of whom would greatly appreciate having their work compared to commercial hunting gear.

Warhol’s name has become synonymous with pop art, a visual art movement born in the 1950s and characterized by the appropriation of images and themes from comic books, print advertising, and other aspects of popular culture that would have previously been considered unfit subjects for a fine artist. According to McCarthy, this appropriation of vulgar imagery resulted in part because painters like Pollock and de Kooning so completely dominated their field many artists felt that abstraction was blocked to them.

“The whole point of camouflage is to blend in with your surroundings, right?” asks an amused McCarthy, who is teaming up with his wife to bring a little context to “The Prints of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again),” a bright and bracing exhibition featuring 63 prints and five paintings on display at the Brooks through September 7th.

“There’s absolutely nothing about this camouflage that blends in,” he says.

“I never think that people die. They just go to department stores.”

— Andy Warhol

It’s been 20 years since Warhol, the bigwig of American pop, blew up his last silver balloon and floated off to shop with Elvis and Marilyn Monroe at the big department store in the sky. But even now, only a month away from what would have been the artist’s 80th birthday, it’s difficult to look at his cartoonish renderings of soup cans and movie stars without asking many of the same old questions: Was he America’s great visionary artist or simply one of its most colorful capitalists? Was he a prankster or a traditionalist struggling to civilize rude new materials and vulgar subject matter in the shadow of abstract expressionism? Or was he P.T. Barnum with a paint brush?

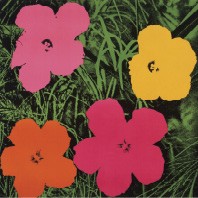

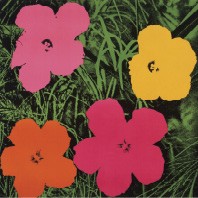

Flower, 1964, Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

“The great thing about Warhol is that you never really know for sure,” Pacini says, standing next to her husband beneath one of Warhol’s aggressively red Elizabeth Taylor prints. But McCarthy offers yet another choice.

“Why can’t he be all of those things?” he asks, adding that it’s always difficult to turn to Warhol’s own commentary for answers.

“Whenever anybody asked Warhol, ‘Hey, where’s the meat?’ he always answered, ‘If you really want to know who I am, it’s all right there on the surface of the artwork.'”

Warhol wasn’t the first artist to sample images from Americana and consumer culture, yet his work is singularly iconic within the international pop art movement. McCarthy and Pacini agree that Warhol’s savvy pursuit of notoriety, combined with his uniquely American attitudes regarding art and commerce, is what set him apart from pop art peers like Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Tom Wesselmann, who all have work on display in “Pop Environment,” another exhibition currently on display at the Brooks.

“Instead of making just one painting, Warhol made prints,” McCarthy says. “That increased his market share. Then he diversified his portfolio by branching out and making films and promoting rock-and-roll music — and it didn’t hurt that the band he promoted was the Velvet Underground. He promoted the Warhol brand endlessly and hired a publicist in the 1960s so that his name would be in the media somewhere every week. And not just in stories about art. He might be on the society page, because he’s been at some party with a lot of celebrities. Suddenly Andy Warhol was the big name.”

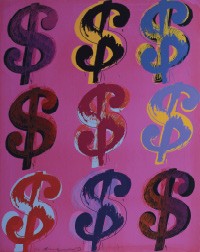

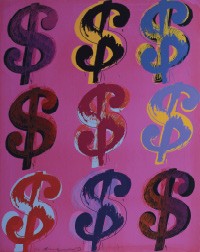

$ (9), 1982, Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

By contrast, acclaimed artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns both picked up commercial work designing department store windows but didn’t like talking about it. Warhol was never ashamed of his commercial work. From his earliest days as an illustrator in the mid-1950s, he was front and center as both a creative force and as a brand name. According to McCarthy, this is the thing that still rubs some people the wrong way.

“As a culture, we somehow want our art to exist outside of economics,” McCarthy says, setting up the artist’s paradox. “At the same time, we’re hard-wired because of our culture to immediately wonder what a piece of art is worth. So if we read in the paper that a painting by Francis Bacon just sold for $24.7 million, nobody cares what Bacon was about, because we now know a Bacon is worth $24.7 million.”

Camouflage, 1987, Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

In addition to having a diversified portfolio and exceptional marketing instincts, Warhol knew how to build networks that reached to the heart of various cultural movements. Looking at one of Warhol’s famous flower prints — an appropriation of a Patricia Caulfield photograph from a 1964 issue of Modern Photography magazine — McCarthy remarks that it may be a kind of homage to New York’s Peace Eye Bookstore and other participants in the 1960s peace movement who were connected to Warhol by way of a vulgar anti-folk band called the Fugs.

Warhol, who left an estate variously valued between $100 million and $800 million, also extended his business analogy through his “factory,” McCarthy explains, referring to the storied 47th Street art studio Warhol kept from 1964 to 1968. “Only this factory would be powered by stars,” he adds. “The stars whose images he used, like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, and also the ‘stars’ in his movies.”

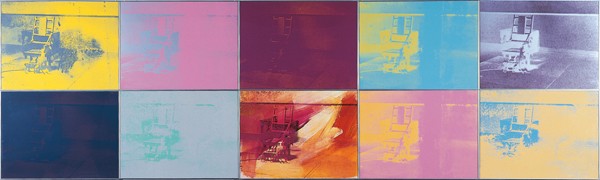

Electric Chair, ca. 1978, Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

“There’s a flip that happens,” Pacini says, referencing the big red print of Liz Taylor. “There’s a period where Andy is painting famous people. Then suddenly he’s as famous or more famous than the people who want him to do their portraits.

“There’s this great Warhol quote,” Pacini says, turning her attention to a smallish pink and red dollar-sign painting and paraphrasing Warhol: “‘People buy a $250,000 piece of art so they can hang it on the wall where other people will see it and know they have $250,000 to spend on a painting.’ Then Warhol asked, ‘Why don’t they just hang the $250,000 on the wall where people can see it?'”

“Being born is like being kidnapped and then sold into slavery. People are working every minute. The machinery is always going. Even when you sleep.” — Andy Warhol

Seeing a large sample of Warhol’s work can be confusing, because it’s so tempting to write him off as the superficial character he played. And then you stumble across one of his electric-chair prints or an ambulance disaster from his “Death and Disaster” series. You realize that in spite of his reputation, Warhol was actively engaging in many of the great cultural debates of the middle 20th century.

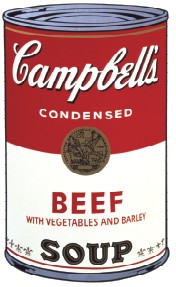

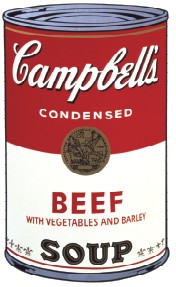

Campbells Soup I: Beef, 1968, Founding Collection, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

In one of his more candid interviews from the early 1970s, Warhol even admitted to harboring political yearnings. When asked if he’d be a better president than Richard Nixon, the spacy wit known for answering reporters with comic non sequiturs became unusually animated and engaged.

“I sure would,” Warhol boasted. “The first thing I’d do is put carpet in the streets,” he said. “And money for everybody.”

Money for everybody. How radically populist. Suddenly his best-known artistic pronouncements all sounded like twisted campaign promises: Fifteen minutes of fame for everyone; Campbell’s soup and Coke for everyone.

“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest,” Warhol once said.

“You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the president drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the president knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.”

“Maybe that’s his end-run around socialism,” McCarthy suggests, strolling past prints of Reagan, Mao, Lenin, and a bottle of Chanel No. 5. “He turns socialism into capitalism. Maybe it’s his way of saying that capitalism can transform any sort of resistance into money. And into a lifestyle.

“His really is the great Horatio Alger story,” McCarthy concludes, reminding us that Warhol, who grew up in Pittsburgh as the son of Eastern European immigrants, was a first-generation American and the son of a coal miner.

“He started with basically nothing,” McCarthy says, “and he completely redrew the map for what it means to be an American artist.”

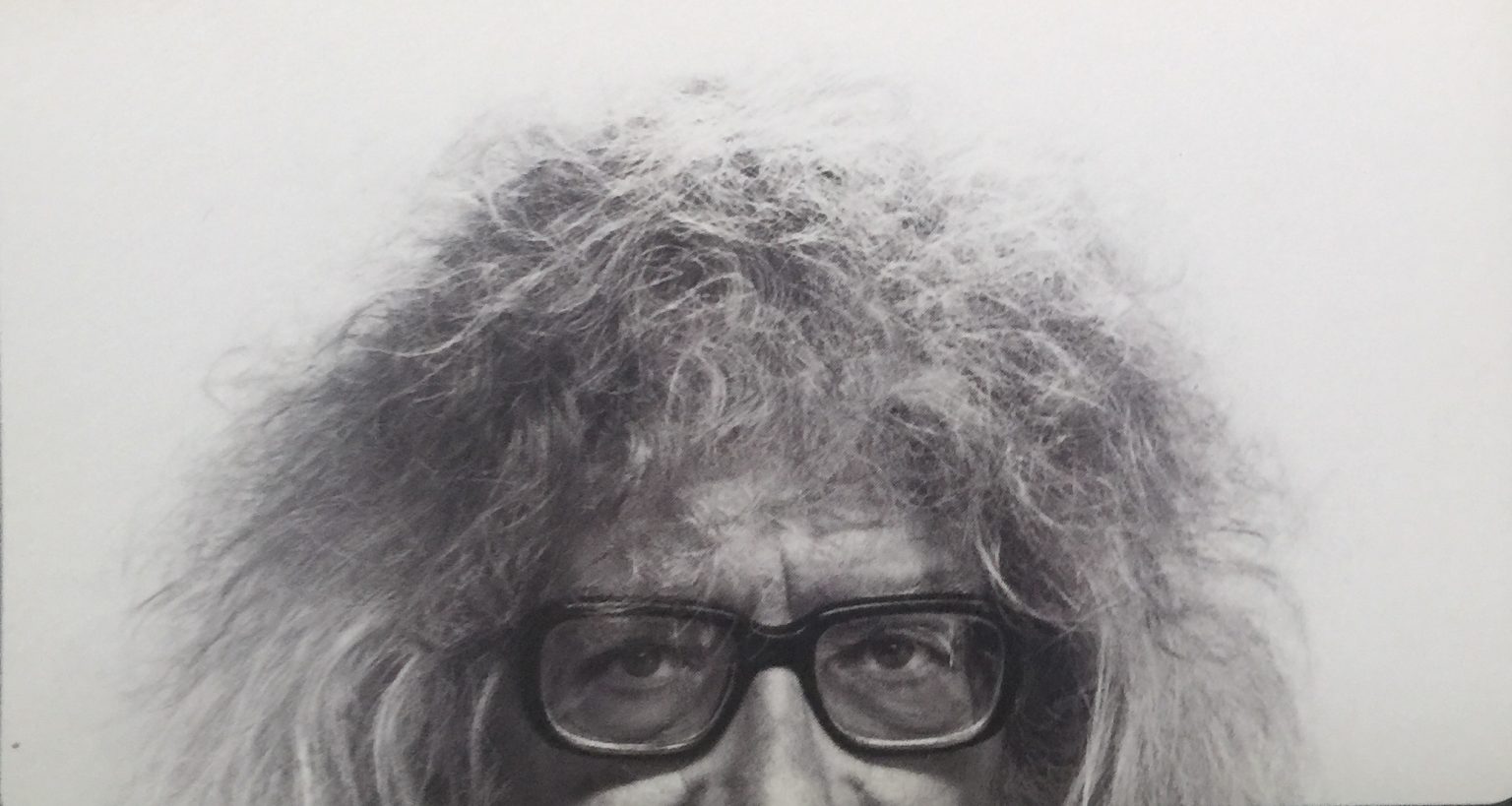

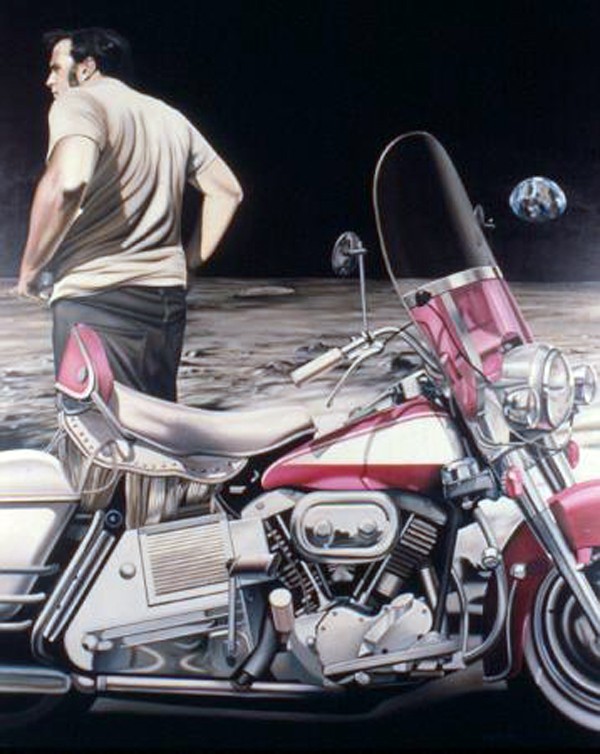

courtesy Philip Pearlstein

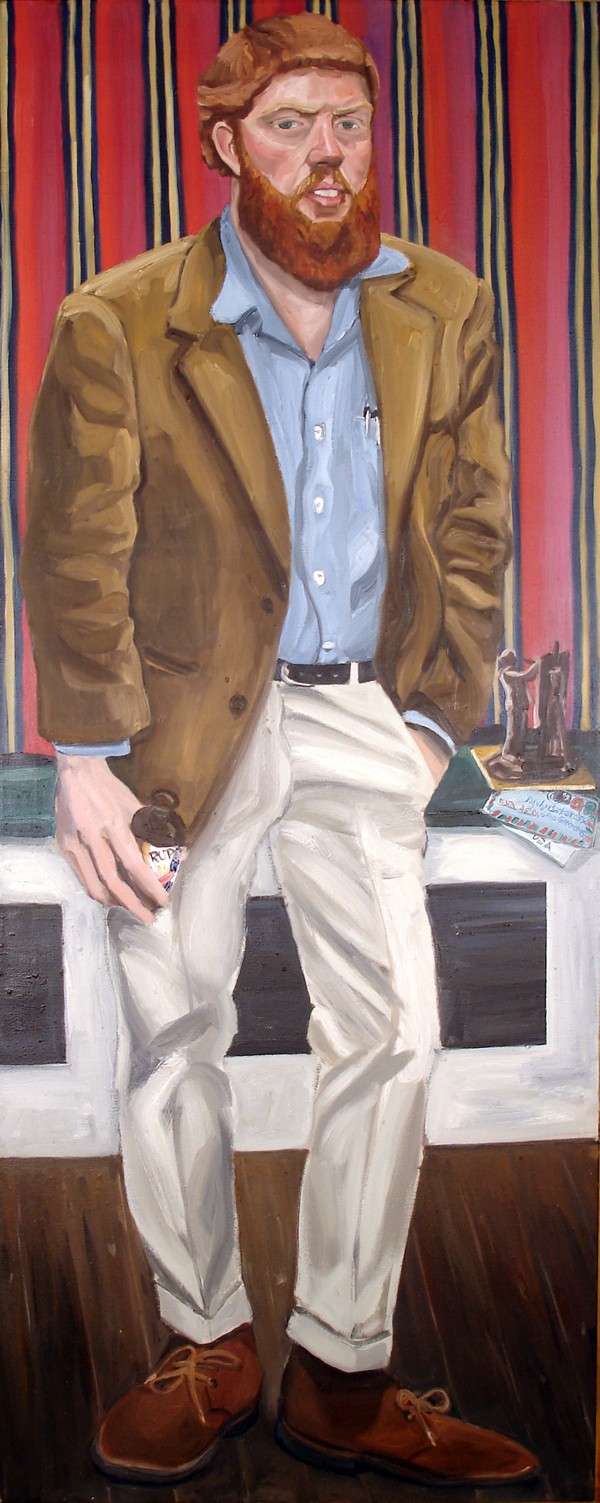

courtesy Philip Pearlstein  Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)  Courtesy Estate of ted faiers

Courtesy Estate of ted faiers  Courtesy David Parrish

Courtesy David Parrish  Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York