The elevation of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to the office of secretary of health and human services is a symptom of a deep problem in the United States: We hate our healthcare system.

There are a lot of reasons to hate the horrifying and deadly kludge that passes for a healthcare “system” in this country. Even the newly installed CEO of UnitedHealthcare, Andrew Witty, admitted in a New York Times op-ed published in the wake of his predecessor’s murder by vigilante Luigi Mangione that no sane person would design a healthcare system like this. And yet, there Witty is, turning the crank on the peasant grinder and collecting the coins that come out the other side. UnitedHealth’s $14 billion in profits, and Witty’s personal $23 million pay, is a powerful motivator for him and his comrades to keep things as messed up (and expensive) as possible. Looking at the United States of 2025, there’s only one possible conclusion: The for-profit healthcare model delivers profits, but it cannot deliver healthcare.

Instead of blaming those who are actually at fault — pharmaceutical companies, hospital conglomerates, and the entire concept of health insurance — many people have been led to reject the things that the people actually practicing medicine do well, like vaccines. Robert F. Kennedy sells snake oil and vaccine skepticism so the public doesn’t turn on the people who are getting rich by making them poorer and sicker.

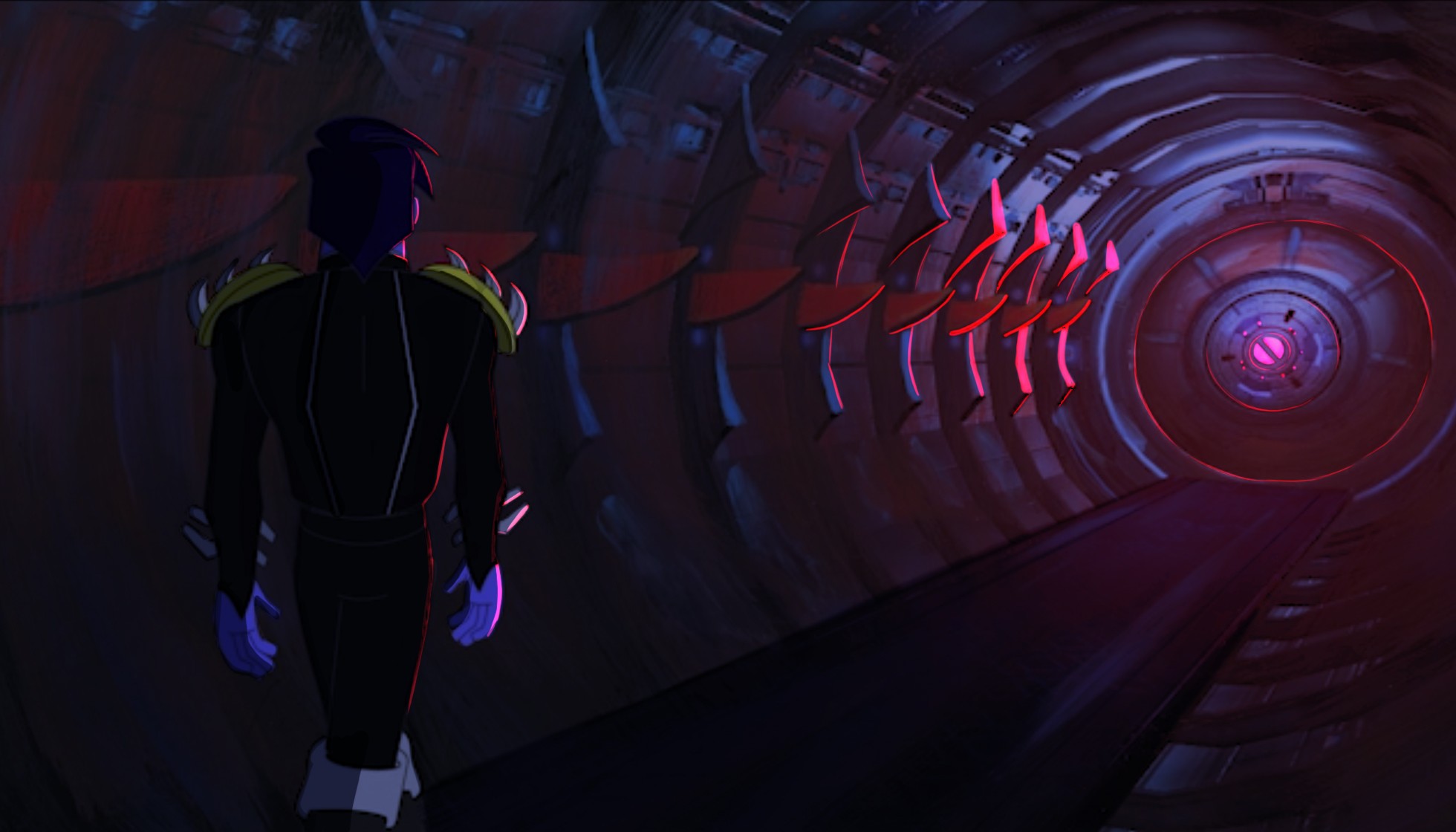

The hero of the new Adult Swim animated show Common Side Effects knows exactly where to place the blame. Marshall Cuso (voiced by veteran comedy writer Dave King) has the look of someone who entered mycology because of his fondness for psilocybin. His Hawaiian shirt is always unbuttoned, his beard is scruffy, and he probably sleeps in his bucket hat. But despite his appearance, he is a serious scholar of mushrooms who studied with Hildy (Sue Rose), a respected academic who has since retired.

Marshall’s mushroom obsession leads him to the jungles of Peru in search of a legendary mushroom known as the Blue Angel. The mushroom is said to have healing properties, but when Marshall finally does find a circle of them, it turns out to be much more potent than anyone imagined. Just a few bites of the little blue mushrooms will cure everything from a rash to a gunshot wound.

The spot where Marshall finds the mushrooms is remote, but it’s hardly untouched. Just a little way upstream is a pharmaceutical factory run by the Reutical corporation, which is polluting the ground and water. Fearing that he might have found the last of the endangered mushrooms, Marshall picks a few samples and makes plans to return home. But before he can, he is attacked by unknown forces and barely escapes the country with his life.

Back in the United States, and in a state of maximum paranoia, he turns to his former lab partner and college friend Frances (Emily Pendergast). She’s a kind soul who has leveraged her biology degree into a healthcare job, and Marshall thinks maybe she could help him bring this miracle drug to the masses, curing practically all diseases overnight. But little does Marshall know that Frances works for Reutical as an executive assistant to CEO Rick Kruger (Mike Judge).

Marshall finds himself trapped with no one to trust but his turtle Socrates, and possibly his half-brother Zane (Alan Resnick). Meanwhile, the mysterious armed men who first found him in Peru are hot on his trail. Their boss, Swiss financier Jonas Backstein, views the mushrooms as a threat to the entire pharmaceutical industrial complex, and wants them and Marshall destroyed.

The way series creators Joseph Bennett and Steve Hely draw both their protagonist Marshall and antagonist Rick reveals a lot about what makes Common Side Effects such compelling viewing. No one is perfect, and no one is purely hero or villain. Marshall sees the world clearly, but he’s also a wild-eyed idealist and something of a self-sabotaging bumbler. He takes everything seriously and carefully calculates his next move to the point of overthinking. Rick is a man of wealth and power, but he has no intention of using his position for anything but self-enrichment. He can barely check into a hotel without Frances’ help.

Meanwhile, Frances must care for her mother Sonia (Lin Shaye), a late-stage Alzheimer’s patient whose insurance is about to kick her out of the nursing home. Rick is afraid the company’s recent disappointing earnings report is going to cost him his job, and he needs a new breakthrough medicine to satisfy the board of directors. Frances finds herself caught between loyalty to her friend and the needs of her job. Meanwhile, Marshall’s reappearance in her life has rekindled an old flame, and her current boyfriend Nick (Ben Feldman) is an oblivious oaf.

Bennett was also a producer of Scavengers Reign, the excellent sci-fi animation that was canceled by Netflix after only one season. The animation style of Common Side Effects is a similar combination of naturalistic environments and somewhat stylized character designs. Adult Swim is famous for the absurdist style of animated comedy the network pioneered, but this show, while often funny, is their first foray into serialized thriller. The laughs come from the character’s foibles, like Rick’s inexplicable addiction to playing farming simulator games on his phone while he should be working. Don’t let the animation fool you into thinking this show isn’t a serious work of art. Common Side Effects is one of the best shows on television.

The Common Side Effects season finale airs on Adult Swim on Sunday at 11:30 p.m. The entire series is available for streaming on Max.

Lawrence Matthews, ‘Vote III’

Lawrence Matthews, ‘Vote III’  Still from ‘The Secret of Kells’

Still from ‘The Secret of Kells’