It was a rough week to be a gay, black man in the South, although I imagine every week is similarly rough. The two decisions last week by the Supreme Court were enough to give a civil libertarian whiplash.

On one hand, the court ruled the Clinton-era Defense of Marriage Act to be unconstitutional, paving the way for

same-sex marriage equality under the law. On the other hand, the majority of justices kicked out the cornerstone of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, allowing states with a history of discriminatory voting practices to charge full-speed ahead with the very same onerous legislative trickery that brought them under Justice Department scrutiny in the first place.

After Chief Justice John Roberts voted with the majority on the legality of Obamacare, I thought perhaps the court might assume a more moderate tone, but I guess that was an aberration. Or was this an aberration? Every time the Supreme Court goes into session, I don’t know whether to crawl under my desk or get out the flowers and balloons. The declaration by Justice Roberts that “our country has changed” is true enough, but it was followed by the plaintiff’s attorney’s astonishing remark that “the problem to which the Voting Rights Act was addressed is solved,” which made us laugh out loud at my house. We figured the lawyer didn’t live around here, but the case was brought against the Justice Department by Shelby County, Alabama. Roll Tide.

The Voting Rights Act was purchased in blood, but Roberts and company either have short memories or they choose not to remember. The act was passed in the wake of “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, when a group marching for voters’ rights was attacked and beaten by police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Representative John Lewis took a rock to the head that fractured his skull, while others were trampled or pummeled with nightsticks. Of the court’s ruling, Congressman Lewis said, “The Supreme Court has struck a dagger into the heart of the Voting Rights Act.”

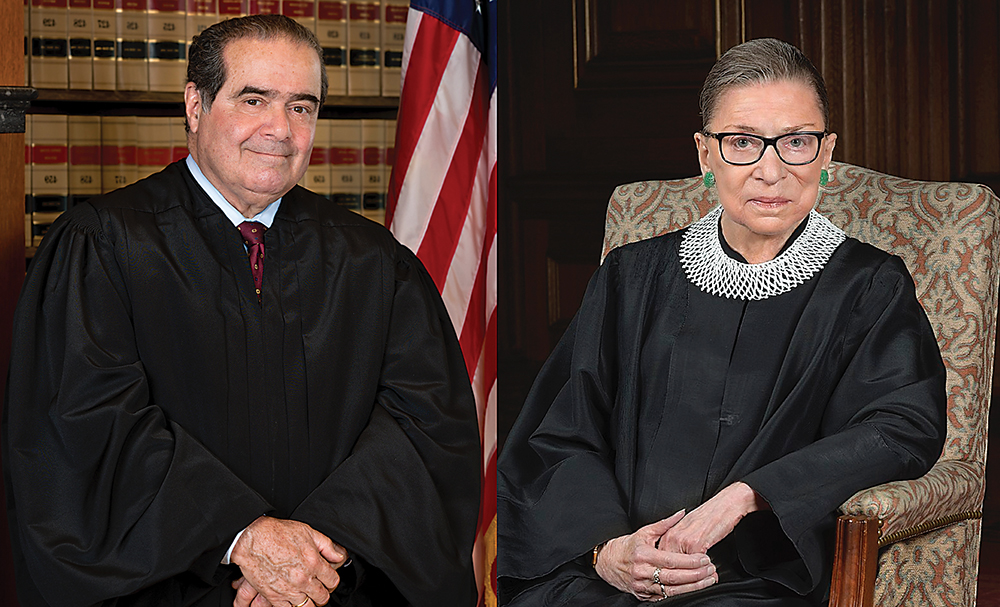

A provision of the 1965 law singled out 15 Southern states, with the notable exception of Tennessee, and a slew of municipalities elsewhere that had a history of voter suppression. It stated any future changes in voting laws must first be approved by the Justice Department. Even Roberts, citing the Freedom Summer of 1964, when three young activists were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi, for attempting to register black people to vote, said, “There is no denying that, due to the Voting Rights Act, our nation has made great strides.” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in rejoinder, said, “The sad irony of today’s decision lies in its utter failure to grasp why the VRA has proven effective.” The great strides have been made because of the VRA. The decision frees nine states, mostly in the South, to change their election laws without advance federal approval.

Although some have said the VRA is dead, the courts have thrown the decision whether or not to reinstate the act back to Congress, proclaiming they can reimpose federal oversights, but they must be based on contemporary data. That sounds reasonable enough, until you consider that Texas officials quickly announced that a voter ID law that was previously blocked under the VRA would go into effect immediately. Florida is now free to set early-voting hours and cut down on polling places in ethnic areas. Governor Rick Perry must be dancing a Texas reel knowing that he need no longer give a second thought to the legality of the redistricting maps drawn to protect Republican seats.

Speaking for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia, son of Italian immigrants, said, “Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get out of them.” Since when is the right to vote an “entitlement,” especially a “racial” one? In John Lewis’ words, “The literacy test may be gone, but people are using other means, other tactics and techniques” to suppress the black vote. Instead of Jim Crow era poll taxes, Republican-controlled Southern state legislatures use pesky and costly photo ID regulations and restrictions on early voting to remain in power.

Scalia claimed his allegiance to DOMA was criticized, “because it is harder to maintain the illusion of the act’s supporters as unhinged members of a wild-eyed lynch mob when one first describes their views as they see them.” Lynch mob? I thought only Judge Thomas accused his detractors of such a thing. Scalia later surmised that gay marriage was inevitable “when the Court declared a Constitutional right to homosexual sodomy.”

It was joyous to watch the parade of weddings in California on cable news, particularly the one between Jeff Zarrillo and Paul Katami, who successfully challenged Proposition 8 before the court. Isn’t this what critics of the gay “lifestyle” always wanted? If gay people can enter into lasting unions, it eliminates the prejudicial perceptions of promiscuity and replaces it with those of loving relationships.

But then there’s Texas, whose governor said, “It is fairly clear about where this state stands on that issue.” I’m sure all Texans don’t agree with Rick Perry, but the state passed an amendment to ban same-sex marriage in 2005 with a 76 percent majority, exceeded only by similar vote totals in Louisiana and Alabama. But gay weddings are coming to Texas, even if it takes some time, and even while the state legislature fast-forwards its attempt to gerrymander Hispanics and African Americans out of the political equation. The Supreme Court’s decisions may have far-reaching societal consequences, but for a gay, black man in the South, it was just another week.

Randy Haspel writes the blog Born-Again Hippies, where a version of this column first appeared.