In “Sleepless,” the current exhibition at Clough-Hanson, Jan Hankins, an accomplished painter known for his astute and sardonic mural-sized observations regarding politics, plumbs the dark waters of the subconscious. Hankins’ methodology is ingenious. With plastic replicas of characters from science fiction, classic tales of horror, and adventure films, he creates scenes of apocalypse that represent the conflicted impulses of the human psyche — the desire for relationship, for power, for pleasure, for immortality.

The psychic battles that rage in Hankins’ paintings are often complex free-for-alls between morality, instinct, and reason. In Lamb O’ God, the sacrificial lamb becomes a 22-karat, testosterone-filled ram that looks down from a high precipice as an F16 bombs an already devastated landscape. The head of a scientist becomes a gun turret from a battleship in Madness, and in The Blind Beating the Blind, God (with white hair and beard and a halo as heavy as an anvil) whispers prohibitions in the ear of a hunchback who is jacking off.

A Day in the Life looks like a ribald simulation of the evolution of the id/ego/superego in which the Creature from the Black Lagoon emerges from primordial waters with gun and money in his webbed hands, a policeman with angel wings points a gun in our face, and a mummy dressed in the American flag leaps out of a pile of manure, roll of toilet paper in hand.

No humor seems too dark, no exaggeration possible in a world where nuclear weapons and self-righteousness proliferate, genocide is alive and well in Darfur, and cloning humans is a distinct possibility. The surreal is tomorrow’s reality, and many of Hankins’ works have this at-the-edge quality, including Dominion Over, in which nightlights on the tanks of a chemical plant shine like Christmas lights in an otherwise blacked-out world. A giant ant straddles a flask and towers above Dr. Jekyll’s laboratory table. Bambi crouches below on a tiny island surrounded by black water.

Dark waters (an appropriate symbol for pollution, global warming, and clouded psyches) inundate much of the landscape in this body of work. A few survivors stand on top of rocks, stone pedestals, and piers. Fifi the pampered poodle (Yak with Fifi, acrylic on canvas) sits on top of an ice floe all dolled up with ribbons and flowers in her hair. She’s bright-eyed and slap-happy and oblivious to the snarling wolves that approach her.

Black water almost covers the stone pedestal on which the muscle-man in Blauburgunder stands. This Schwarzenegger look-alike has one foot on a treasure chest and is wrapped in the colors and stars and stripes of the flag. His tattered trousers are red-and-white-striped. His arms have become wildly gesturing, brawny legs that wear blue boots covered with gold stars. Blauburgunder — an Austrian word for the red Pinot Noir grape — refers, perhaps, to a politician drunk with power, money, and patriotism. In spite of the black water lapping at his ankles, he’s still grinning, still swaggering, as clueless and excited as Fifi.

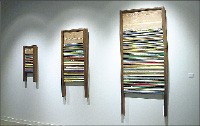

Mirrors placed beneath three untitled toy models (including the one on which Blauburgunder is based) reflect gallery lights and cast shadows of figures onto the wall, creating dramatic plays of light and dark that intensify our sense of the struggles that go on within the heart and soul. Light streaming from beneath the plastic replicas and climbing up the gallery wall, rather than shining from above, brings all kinds of truisms and metaphors to mind, such as removing the sty from our own eyes and looking for truth inside.

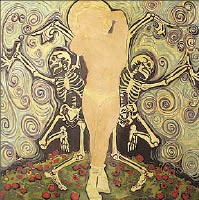

In a series of oils on canvas (Sleepless 1, 2, and 3) and in two untitled plastic models, hope regarding the human condition can be gleaned from Hankins’ retelling of a classic tale of horror and romance. In Sleepless 2, water roars across the landscape and around Frankenstein’s monster, a stitched-together creature whose head is sewn on backward. The creature’s arms and torso reach toward the gravesite on which he stands. His head and lower body strain toward his bride, who is bandaged from neck to foot and strapped to an operating table. Beneath the table, a panther devours a human heart. In this scene of raging emotions and thwarted desires, another bandaged creature (or another aspect of the feminine) rises from the bride’s chest. Its swollen right hand reaches for a rose engulfed in light.

Wide-eyed and wide-awake in “Sleepless,” Hankins goes into the dark and shines light on wounded, misguided, deluded creatures who can still reach for beauty. His cast of characters — by turns funny, frightening, and poignant symbols of the human psyche — provide a blueprint for us all.

At Clough-Hanson Gallery, Rhodes College, through December 6th