Currently on view are two exhibitions inspired by Horn Island, the tiny Mississippi Gulf atoll made famous by Walter Anderson’s visionary watercolors and woodprints.

In “Horn Island 23” at the Memphis College of Art, a storm rages on the wall in the form of Trice Patterson’s mixed-media work Some Early Morn. A long piece of frayed canvas fastened with twine to weathered wood looks like a battered tent onto which the artist has scumbled and scrawled charcoal dust, ink, and black Conté crayon. At bottom right of the storm, we can just make out two delicately drawn pines — Patterson’s haunting tribute to Horn Island’s trees, many of which were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

Don DuMont, the MCA adjunct instructor who led 30-plus colleagues, students, and alumni during the eight-day stay on Horn Island in June, contributes a well-crafted piece of whimsy to the show. A large raven, mouth open and cawing, strides across the top of DuMont’s Box of Squalling Riches. Crows carved into the sides appear to fly around the box in all directions. Instead of a golden ark, these squawking, intelligent keepers of the covenant guard a freshly hewn cedar/cypress container that could be a coffin for a small animal or a Pandora’s box full of Horn Island mosquitoes, blistering temperatures, high winds, freedom, and excitement.

Much of the artwork in “Horn Island 23” is a microcosm of the island. The sleek, steel seabird torpedoing in for the kill in Bill Price’s Cooling Wind is backdropped by Lance Turner’s large acrylic abstraction of ebb tide in Map of Horn Island Sand. Close by, Richard Prillaman’s copper Toad simulates the glossy slime covering the creature and the iron-rich mud in which it wallows. Matt Wening’s stark digital prints line the gallery’s right wall with dead trees that stand like sentinels on deserted beaches.

Untouched paper becomes a large sand dune in Jason William Cole’s accomplished watercolor Palms. At the crest of the dune, Cole gestures tufts of dead grass and a knee-high cluster of scrub and dwarf trees. Above deep-green palm blades, blue and purple washes create the impression of windswept sky.

Black lines of acrylic, twisting furiously in all directions, record the fight for life, the futile attempts to fly, and the death throes of Lisa Tribo’s Broken Wing Crow. A Spiral in the Sand, Lance Turner’s large acrylic on canvas covered with hundreds of hand-painted, near-white concentric whorls, creates the sensation of being sucked into and spit out of swirling sand and water.

Several of Tessera Phipps’ giclée prints look like pure geometry. Look closer. Puckers in the material of her white triangles and pointed arches, her brown “Xs,” and her titles (Inner Sanctum, Temple Door) suggest the artist was flat on her back looking up at securely fastened tent flaps when she conceived these images.

To photograph his unsettlingly existential Night Sky Over Main Camp, James Carey stood close to shoreline. With a wide-angle lens and a 30-second exposure time, Carey captured a band of artists under thousands of tiny points of light at the edge of civilization and infinity.

“Horn Island 23” at Memphis College of Art through September 21st

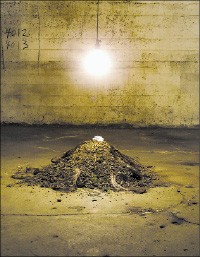

In “Eight Days in Exile” at Studio 1688, Willie Bearden, using infrared filters, lens flares, and Photoshop manipulations, transforms Horn Island’s already exotic landscape into post-apocalyptic visions of Eden. A horizon lined with leafless black trees stands in stark contrast to the luminous white scrub bushes, sand, and clouds in Bearden’s giclée print, Horn Island Reflection.

Robin Salant’s archival prints of shell and bone floating in black space bring to mind Edward Weston’s images of nautilus shells. But, instead of pure form, polished surface, and the graceful curve of Weston’s shells, Salant’s shells and bones, all broken and scarred on Horn Island, are more idiosyncratic and provocative.

The back of a catfish skull, picked clean by predators and bleached by the sun in Bone Study #1, looks like a pig snout, a satanic icon, the face of a wolf, and/or webbed wings wrapped around the body of an albino bat. Salant’s image of the orange-red incisors and pitted skull of a rodent, Bone Study #3: Nutria, brings to mind talismans that tribal people believe can channel the forces of the universe.

“Eight Days in Exile” at Studio 1688 through September 20th