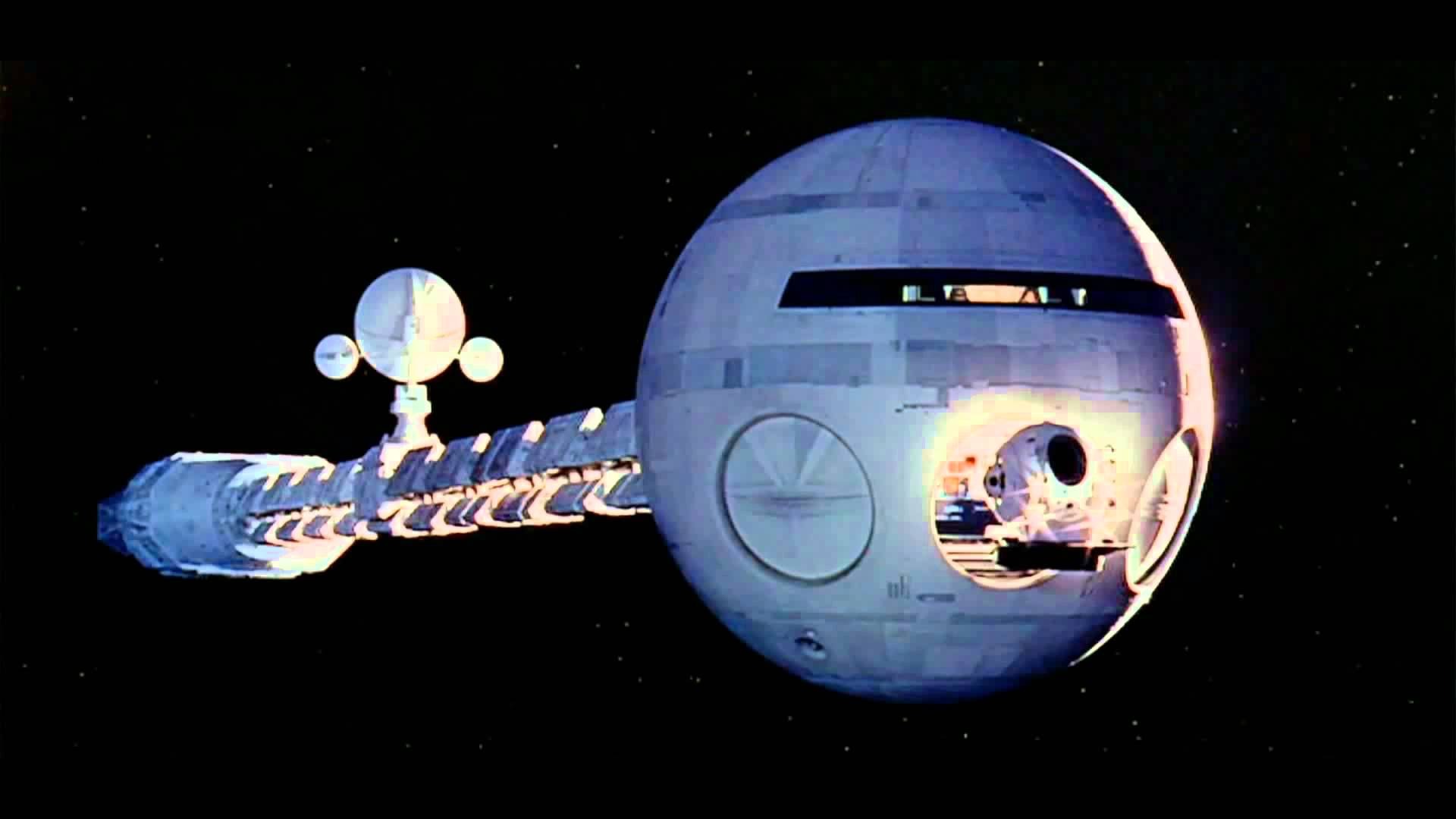

The Discovery on its way to Jupiter in 2001: A Space Odyssey

The first time I saw a Jackson Pollock painting in person was at the Art Institute of Chicago. The amazing thing about Greyed Rainbow was not necessarily the patterns that seemed to emerge from the visual chaos—it was that the closer I got to the 8-foot-tall canvas, the more patterns emerged. No matter how close you look, the spell is maintained. It’s art that works on both the gigantic and intimate scale.

I first saw 2001: A Space Odyssey on a beat-up VHS tape I rented from a small-town video store. I could barely understand what was happening in the story, and, to a kid raised on a steady diet of music videos, it moved very slowly. But it was absolutely fascinating to me. Even if I couldn’t say I loved it like the way I loved Star Wars, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. And I had to admit, it looked better than Star Wars. This was not space fantasy. It was a documentary from the future.

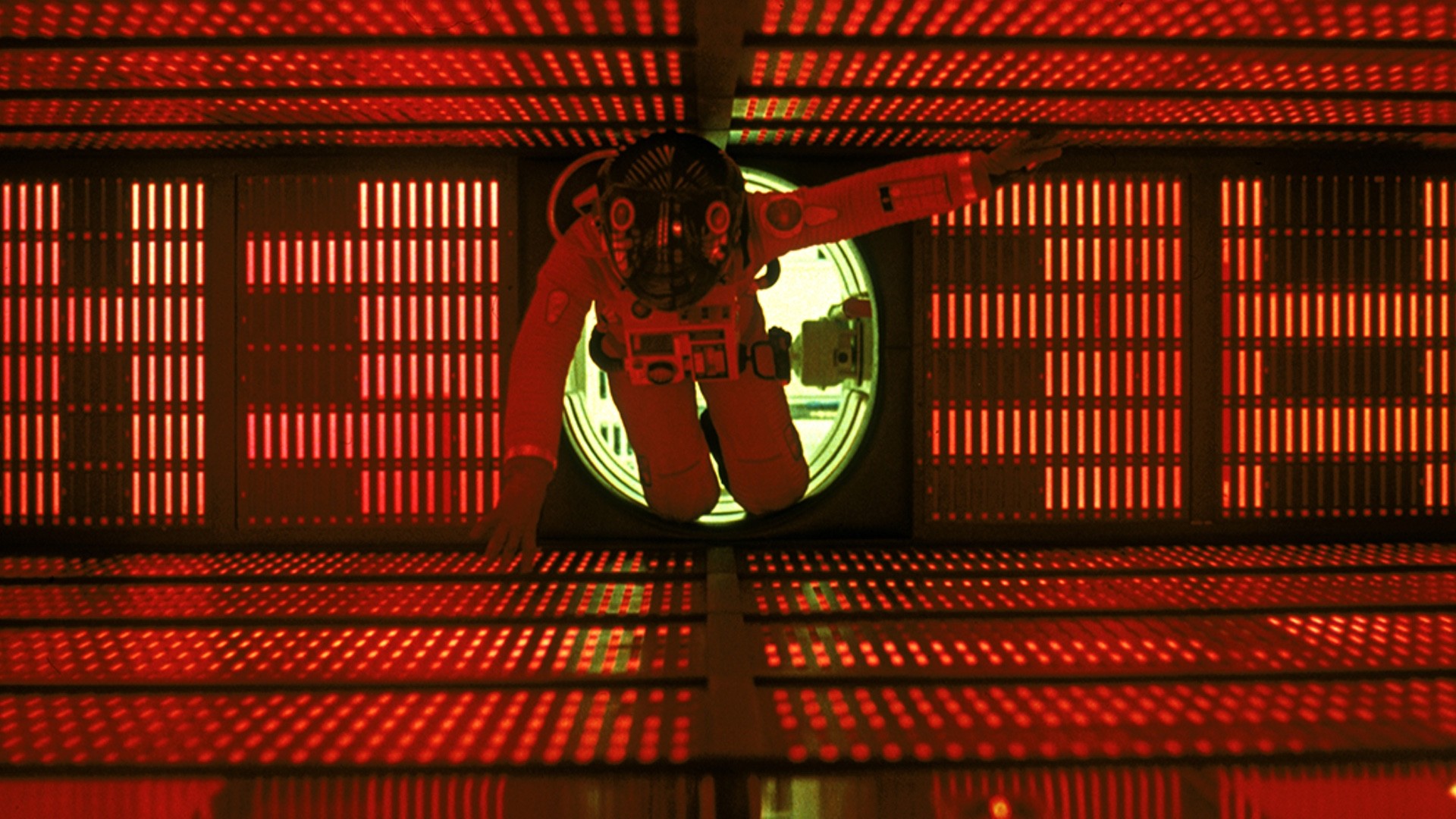

David Bowman (Kier Duella) confronts the rogue computer HAL.

Only after I read Arthur C. Clarke’s novel, which was developed in parallel with the film, did the real scope of the story sink in. This was not sci fi in the “what if flying cars?” sense, but a work that treaded in spaces usually reserved for religion. Why are we here? What is our purpose? What comes next?

As the years passed, and technology developed, I saw 2001 on bigger and bigger screens. VHS gave way to DVD, which progressed to Blu-Ray. Tube TVs went HD (yes, I had a 1080p capable CRT), then gave way to plasma and LCD flatscreens and 4K. At each turn, I made a point of watching 2001 again, and every time it looked better and better. This was not the case with all beloved films. (Remember the terrible masking job in The Empire Strikes Back that gave the TIE fighters little moving frames?) Like Greyed Rainbow, the spell was maintained no matter how close you got. Special effects created during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration have held up better over time than The Phantom Menace.

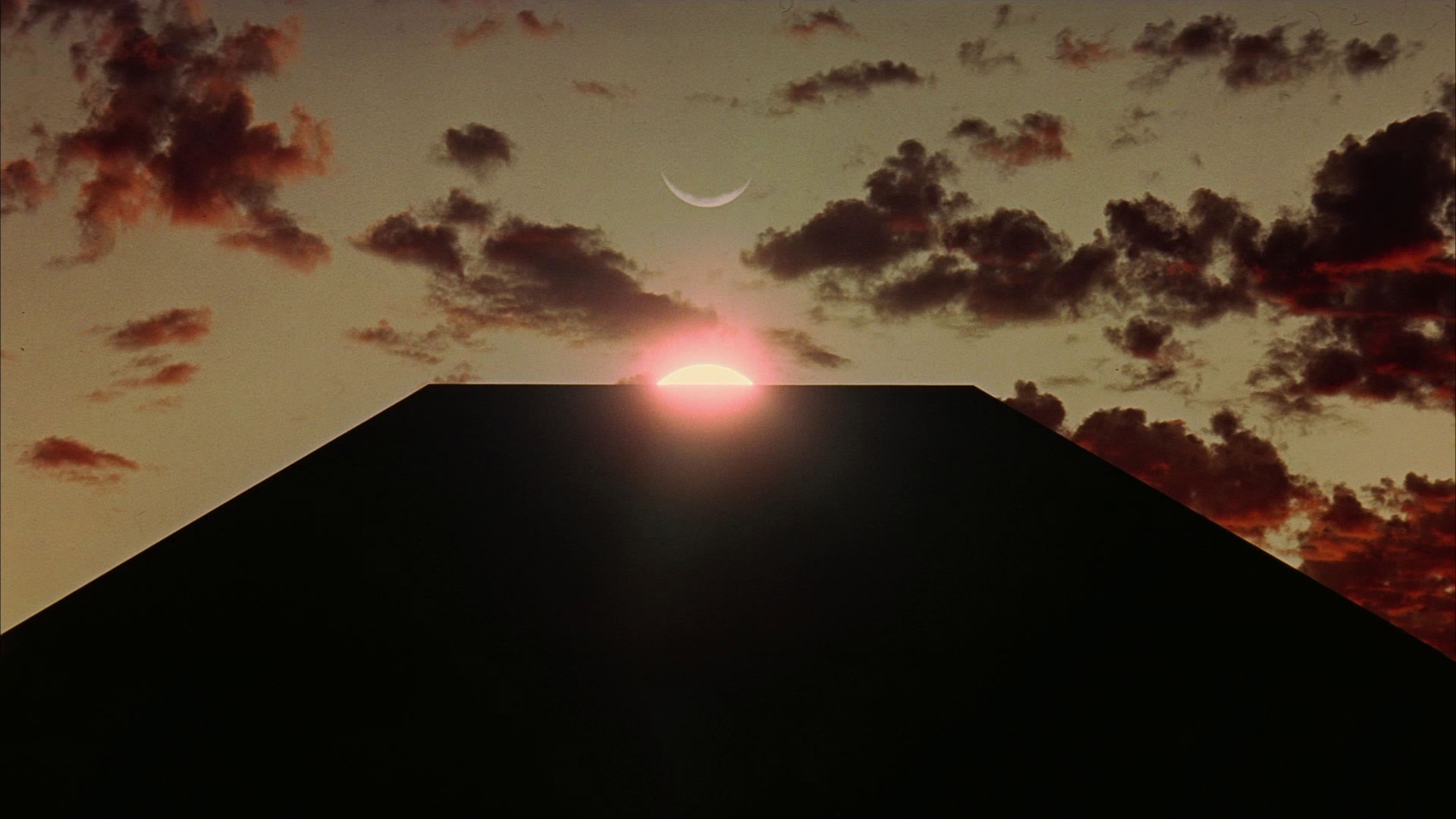

Sunrise over the Monolith

Part of the reason is because 2001 was made on 70 mm film—twice as wide as standard 35 mm film—and designed to be projected in places like the 86-foot wide screen at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles. The theater industry’s answer to television has always been to build bigger screens, and Cinerama was the ultimate expression of that idea. 2001 seems slow because it is designed to be immersive. Kubrick wants to give you time to look around.

For the next week, Memphis audiences will get a chance to see 2001: A Space Odyssey the way it was intended to be seen in a special engagement at the Paradiso IMAX. The Dark Knight director and Kubrick superfan Christopher Nolan has championed the film in its 50th anniversary year by striking new 70 mm film prints that have screened in theaters nationwide still equipped with the necessary monster film projectors, and the program has been so successful that MGM expanded it into digital IMAX theaters.

The myth of 2001 has grown larger than the Cinerama Dome. Countless words have been written about it by critics of all stripes. (I once did 20 pages about the anthropomorphization of technology in the film—how the machines seemed to become more human, and the people became less human.) Beginning with Clarke’s own The Lost Worlds of 2001, every book-length effort to explicate its mysteries has only added to them. Michael Benson’s recent Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece is the first one I’ve read that treats the film less like a quasi-religious text and more like a work of art made by flawed human beings. Particularly moving is the portrait Benson draws of Clarke as a deeply closeted homosexual who fled his native England for Sri Lanka after the prosecution of computer scientist and war hero Alan Turing for indecency. Clarke’s intellectual life may have been spent in the highest orbits, but his personal life was a string of hustlers and grifters taking financial advantage of his emotional naiveté.

Astronauts Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) and David Bowman (Keir Duella) discuss the fate of their sentient computer crewmate HAL 9000. This composition is a reference to a shot from Citizen Kane.

Kubrick comes across as considerably less sympathetic. His ruthless business dealings drove his presumed partner Clarke to the brink of bankruptcy, and his unforgiving creative methods drove the people around him beyond the brink of madness. For four years, Clarke wrote and re-wrote narration intended to explain the action on the screen, only to have Kubrick decide at the last minute that it wasn’t needed. In the scene where astronaut Frank Poole’s body is recovered in space, the stuntman in the space suit had actually passed out from lack of oxygen because Kubrick wouldn’t allow air holes to be drilled in the helmet. The editors assembled the film without a script, because Kubrick had the whole thing in his head and refused to write it down. After the production was over, Kubrick demanded that the one-of-a-kind, slit photography machines Douglas Trumbull designed and built by hand be smashed to bits so no one could ever replicate the climactic Star Gate sequence.

But all of Kubrick’s instincts turned out to be right, and Clarke forgave him in the end. After all, if 2001: A Space Odyssey wasn’t the highest grossing film of 1968, Clarke wouldn’t have been on TV sitting next to Walter Cronkite when Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969. The film’s financial success was far from guaranteed. The opening night in New York was such an epic disaster that Kubrick moved to England and never came back. But like The Beatles or Kanye West, it turned out to be one one of those rare times in pop culture history when the market and the cutting edge met.

Choreographer and mime Daniel Richter as Moonwatcher. The rest of the hominids in the wordless Dawn Of Man sequence were played by teenage girls from a BBC dance troupe.

Clarke and Kubrick set out to make the “proverbial good science fiction film,” and in many ways, the future they envisioned came true. Maybe we don’t have a moon base, but the astronauts on the Discovery get their daily news from things that look a lot like iPads, and rogue computers are indeed a major problem here in the 21st century. But it also points to the limits of the Western science fiction vision. Global climate change, the most pressing scientific issue of our time, is not mentioned, and while there are women scientists (who are presumed to be Soviet Russians, by the way), there are no black people in space.

Bowman uses a tablet computer to catch up on the daily news from Earth. The iPad made its debut in 2010, the year when the sequel to 2001 was set.

Yet every other film that has dared to shoot for the same Clarke orbit as 2001 has gone down in flames. The Soviet response, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, is much more human sized. The sequel, 2010, made with Clarke’s influence but not Kubrick’s, is a mere footnote. Nolans’ own attempt, Interstellar, falls apart at the end under the weight of the director’s sentimentality and instinct to explain himself. 2001 remains a singular product of a particular time, when the American future seemed bright and limitless, and capital could still be brought to bear for great works of art. But its awe is tinged with fear, as are all good religious texts. If we are to be transformed by our technology and our knowledge, will our wisdom follow? If we are to become more than human, what will be lost? Like Hal’s red eye, 2001: A Space Odyssey looks unflinchingly at these questions, and reveals the paucity of our answers.

The Lost World of 2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey plays at the Malco Paradiso IMAX Theater August 23-30.