As I drove down the winding highway to the small East Tennessee city of Athens last Thursday, I wondered what the next day’s Tennessee Historical Commission meeting would hold. Under no circumstances did I think the members of the commission would approve Memphis’ waiver request to remove Nathan Bedford Forrest’s statue from our public park.

And as I anticipated, the waiver was denied, and “leave history alone” was a recurring theme of the morning.

After Mayor Jim Strickland pleaded with the commission to vote on the city’s request and other officials spoke both for and against the statue, a pro-Forrest teacher from Memphis was the first to take the podium for public comment.

She began her two minutes by saying, “It seems that this day and time everyone is trying to make everything pleasant and fair for everyone.”

I was baffled. Why is it wrong that people of color want a pleasant and fair experience sans a monument of a Ku Klux Klan grand wizard when visiting a public park?

Isn’t that what America is supposed to be all about? Do civil rights not grant everyone the privilege of fairness — especially in public places, if, after all, we live in a country with “liberty and justice for all”?

Continuing to justify why Forrest should be glorified and his statue untouched, the teacher went on to talk about the general’s late-life conversion to Christianity, how he begged for forgiveness for the number of people he mistreated, and turned his life around as a result. “Didn’t Christ forgive us for our many sins? If God can forgive Nathan, why can’t we?” she asked the room.

I can’t speak for everyone in this city or all people of color, but I forgive Nathan. I don’t hate him. I, like many others, would just prefer for him not to be memorialized with such grandeur in a public space in my city.

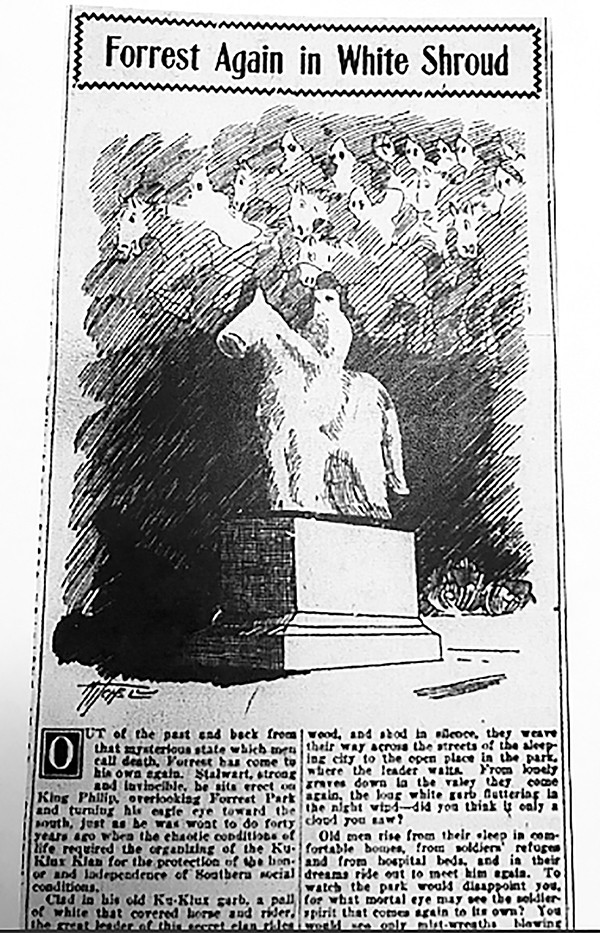

At Friday’s meeting, Mayor Strickland referenced this article from the Memphis News-Scimitar that was published when the Forrest statue was erected in 1905.

Also, what Forrest did in his personal and religious life is not our concern or a relevant justification for having a statue of him in a public park. He might have repented for his wrongdoings, but that doesn’t change what he did, who he was, and what he stood for.

“The next thing y’all will want to remove are the crosses from our many churches. When does the insanity stop?” the teacher asked rhetorically, as her allotted speaking time ran out.

Was she legitimately putting Nathan Bedford Forrest in the same category with Jesus Christ?

How does a Confederate army general and KKK grand wizard compare to a man that only preached and practiced love. That’s insanity.

After the teacher’s two minutes were up, Lee Millar, the spokesperson for the Sons of the Confederate Veterans, was the next to speak.

He claimed that “thousands and thousands” of Memphians support the statue and the history it represents, saying that the statue and history should be left alone.

I understand that history is important. But I don’t understand why someone on the losing side of history deserves a statue. And I definitely don’t understand why the statue of an oppressor is the kind of history that people want to hold on to.

Also, if keeping history in place is the argument for keeping the statue where it is, then it’s faulty. The only history that ever took place where Forrest is buried is the empowerment of whites and the demoralizing of blacks. Which part of history does the statue really honor?

Not the Civil War. As Mayor Strickland pointed out earlier in the meeting, the park where Forrest and his wife are buried now was not a Civil War battle site.

The statue was not erected until years after the war, just as Jim Crow laws were becoming enacted in the South. It was 40 years after the war when the bodies of Forrest and his wife were disinterred from Elmwood Cemetery and moved to the park where the statue was dedicated. The mayor said the park was a landmark that many African Americans passed daily on the way to work, ensuring that Forrest would be ever present and so would the laws of Jim Crow.

“Simply put: This is a monument to Jim Crow,” Strickland said.

I agree. The statue’s got to go. Move Forrest and his wife to a museum, back to a cemetery, or anywhere else but a public park in a majority black city.

Maya Smith is a Flyer staff writer.