AudioGraphic Masterworks (AGMW) began in 1997 as a project of Brandon Seavers and his partner, Mark Yoshida. The company was located on Summer Avenue in a 500-square-foot office, where Yoshida and Seavers would first begin their journey into multi-media productions. Seavers and Yoshida were the only employees.

The company later relocated to Midtown, before building its current facility in Bartlett, in 2008.

Through the years, AGMW developed a strong relationship with Oxford, Mississippi-based label Fat Possum Records (the Black Keys, Wavves, Iggy and the Stooges), manufacturing most of the label’s CDs for more than a decade. At the end of 2013, Fat Possum manager Bruce Watson approached Seavers about what he knew about pressing vinyl records. Vinyl sales were booming, and Watson needed a place close to home to produce his records.

“If you know anything about the vinyl industry, you know that it takes forever to get anything done,” Seavers said.

“The industry has grown to the point where it takes four to six months to get a record pressed and shipped back to you.”

Watson knew this all too well. In 2013, Fat Possum had thousands of Modest Mouse records held in customs in the Czech Republic, costing the label thousands of dollars in lost revenue.

“We had gone through places like United Records in Nashville and Pirates Press, but we couldn’t wait six months for a record anymore, especially since we took on the Modest Mouse catalog and the Hi Records stuff,” Watson said.

“We already knew Mark and Brandon had manufacturing experience, and they were seeing the CD side of things going downhill, so this provided a new opportunity for them as well.”

Vinyl record-making machinery isn’t exactly the type of stuff you find on eBay. Most record presses are nearly 50 years old and are powered by steam. With vinyl’s increasing popularity among audiophiles and music fans, those in possession of a pressing machine know the kind of power they hold.

A few months into their search, Seavers and Watson got lucky. They learned about an old pressing plant in Brooklyn that had shut down — most of the equipment still intact and being stored in New Jersey. They contacted the owner, who said he would only sell if the buyer bought everything, down to the last bolt.

“We started looking for the equipment at the end of 2013, and by the spring of 2014 we were buying this whole pressing plant,” Seavers said. “My wife had a baby in late 2013, so my head was exploding with all this stuff going on. I remember Bruce calling me, and my response was just like, ‘Wow, really? You want to do this now?'”

“We didn’t ever think we would find the equipment in one place, and the guy who owned all this stuff before us looked at it all like it was his pet. He wanted all the parts to go to one family, and he wanted to make sure it was going to people who would take care of it. He was very involved from the beginning.”

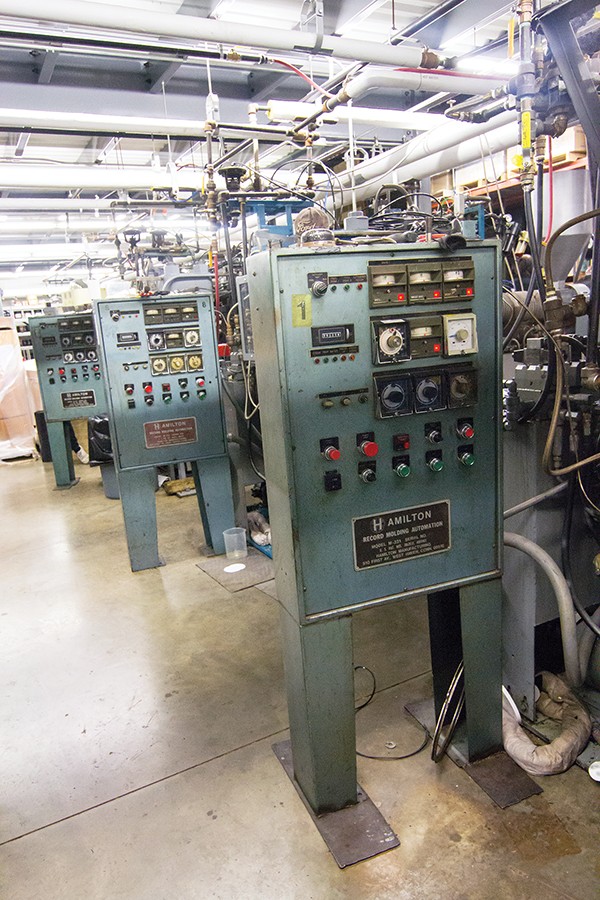

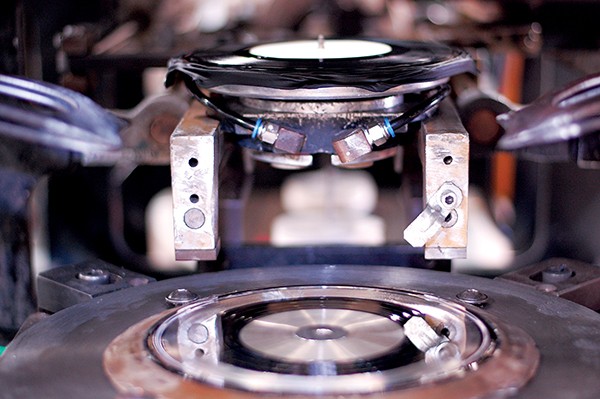

The equipment arrived at the AGMW warehouse in May 2014, 10 steam-powered machines total. The Memphis Record Pressing team spent the next six months setting up their first machine, rebuilding valves, and nearly rewiring the entire thing. Anything susceptible to malfunction was replaced before the machine was used.

“You’re looking at 40- to 50-year-old machines. You put power and steam and pressure on those things, and something is bound to pop,” Seavers said.

“No one really knows what’s going to happen until you fire them up.”

Josh Miller

Josh Miller

A worker at Memphis Record Pressing inspects a record before sending it to the listening station

The Vinyl Guru

When you’re dealing with machines that have been around for nearly half a century, finding the right mechanic can be just as hard as finding the machine for him to work on. Record Products for America is the only company in the country that supplies replacement parts for a record press, and when they can’t accommodate, Memphis Record Pressing has to have their parts custom-made. But what about everyday malfunctions that arise when working with these ancient machines?

Enter Donny Eastland, affectionately known as the “Vinyl Guru.” Eastland worked for Southern Machine and Tool Corp (SMT) in the late 1970s, a Nashville-based company that manufactured some of the machines that Memphis Record Pressing uses. In addition to building record presses at SMT, Eastland installed them and got them up and running in pressing plants all over the world.

Seavers said that after a long search, he was able to track down Eastland — who is in his 60s and nearing retirement — and ask him if he would be interested in making records again.

“Donny was the [potential] deal-breaker. We knew that if we couldn’t get an experienced mechanic that we’d never get this off the ground,” Seavers said.

“It took a little bit of persistence to get Donny on board, but he agreed to commute from Nashville to work for us and to teach all of our mechanics everything he knows.”

With Eastland on board, Memphis Record Pressing is able to run an average of three record presses a day. They are capable of pressing records at 120, 130, and 180 grams. Even with the Vinyl Guru at the helm, Watson said everyone is still learning as they go.

“We were pretty naive going into this. Nothing about it has been easy, and everything has cost twice as much as we thought it would,” Watson said. “I don’t think we were so naive as to think this whole thing would be easy, but it’s been a lot more difficult than we imagined.”

Josh Miller

Josh Miller

Three of the Hamilton Machines at Memphis Record Pressing

A New Press in Town

Since entering the vinyl business, Seavers has doubled his work staff, going from 13 employees to more than 30 — two shifts of workers, whose jobs range from listening to and inspecting each record for flaws to shrink-wrapping and packaging records for FedEx to pick up. Everything is done in-house; even the drop cards (a card inside each record that features a download code) are printed at AGMW.

“The guys that are making these records are artists. It’s definitely an art form because there are so many things that can go wrong during this process,” Seavers said.

“Each job in the process is important. There are people who do nothing but listen to each record and make sure there are no audible mistakes. Then there are our assembly guys, maintenance techs, shipping managers, and customer service representatives. There’s a lot going on in this small workspace.”

Most of the orders Memphis Record Pressing takes on are from Fat Possum and Sony RED, a subsidiary of Sony Records that represents more than 60 independent labels. Between the demands of those two entities, Memphis Record Pressing stays busy, turning out thousands of records a day. Seavers said they aren’t currently taking on any new clients.

“We don’t want to do what the other plants have done, which is to take on more work than what they are actually capable of doing,” Seavers said. “Your quality drops, your reputation drops, and you lose your ability to turn things out quickly. Since the word got out that we bought the equipment, we get calls every single day from people all around the world wanting to send us work, because they can’t get it done anywhere else.”

Seavers said they are hoping to take on new orders by late summer, but the labels they have worked with in the past and local labels such as Goner Records and Madjack Records will still take priority.

Josh Miller

Josh Miller

After a record is pressed, the excess must be trimmed before moving on to the inspection station

Let the Fat Possum Eat

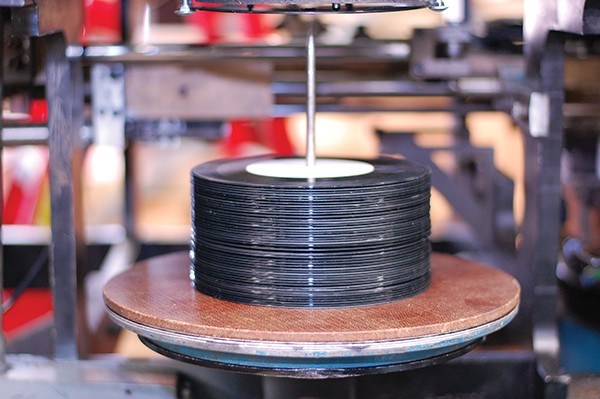

While Sony RED might be keeping the press operators busy at Memphis Record Pressing, Fat Possum Records has also reaped the benefits of having a pressing plant at their disposal. Watson said that Fat Possum moved 300,000 vinyl units last year and that he hopes to be able to move at least 600,000 units this year. In addition to being able to double the company’s vinyl sales, Watson said the pressing plant helps attract bands to his label.

“It’s definitely a selling point when we are trying to sign a band. Everyone is so into vinyl now that it’s become a part of the record deal when we work with someone,” Watson said.

“It’s nice to be able to tell a band that we have our own pressing plant and they wont have to worry about delay. There are so many releases now, where the album comes out, and then the vinyl comes out two months later. That kills a release. Unless you’re a huge act, you have one shot at your release date. That first week is so important because that’s when you usually sell the most records; that’s when the limited editions come out and you start registering on sound scans. If you have to wait two and a half months for your vinyl, you’ve lost all of your momentum on that release.”

Courtesy of Memphis Record Pressing

Courtesy of Memphis Record Pressing

A stack of finished LP’s awaits inspection

The Vinyl Ripple Effect

Fat Possum isn’t the only local label to benefit from Memphis Record Pressing. Goner and Madjack have also tapped Memphis Record Pressing to churn out their releases; meaning local bands of all kinds are also getting in on the action. Madjack recording artist James Godwin said he remembered hearing about a pressing plant coming to Memphis, but he wasn’t sure when and if the rumors would come true.

“I remember hearing about it and thinking that it could end up helping out a lot of local musicians, but to be honest, I thought it was one of those things that might end up happening 10 years from now,” Godwin said.

After cutting Bad To Be Here, Godwin’s first full-length as James and the Ultrasounds, Madjack expressed interest in signing the band and releasing the album on vinyl. According to Godwin, Madjack first contacted United Record Pressing in Nashville and was told that it would be months before the record came out.

“I was planning on touring around the release, and I had the dates already booked. I was told we wouldn’t even have my records when we got back from the tour,” Godwin said.

Instead, Madjack Records worked up a deal with Memphis Record Pressing, and the single was done in a month. Godwin called Memphis Record Pressing “one of the last missing pieces of the puzzle” for Memphis music.

“I think it’s really important to have a local pressing plant in Memphis. When you go on the road and take a box of CDs with you, chances are you’re coming home with that box of CDs. If you have vinyl on the merch table, people buy it, because they know it’s limited,” Godwin said.

“There are also a lot of things that can go wrong in the process of making a record. I’ve looked at the forms you have to fill out at United, and I remember thinking, ‘Man, I’m not trying to get a job here. I just want a record put out.’ Having something this close to home really makes a difference, it makes you feel more connected to what’s going on with your music.”

Goner Records has already had two singles (“Giorgio Murderer” and “Aquarian Blood”) and an LP (a repress of Nobunny’s First Blood) manufactured at Memphis Record Pressing, with a Nots single and a reissue of a Reatards album currently in production. The Midtown label has had a deal with AGMW regarding the production of its CDs for some time, so it made sense to label co-owner Zac Ives to let Seavers handle the label’s vinyl needs as well.

“The biggest deal is that those guys are really good with managing projects. If you give them a date that you need to have something done by, they do everything they can to make it happen. That’s just not the case with everyone else,” Ives said.

With less wait time in between record releases, Ives said that the label isn’t locked into a certain process dictated by the pressing plant.

“We can go out and listen to a test press and approve it and it’s ready to go, instead of waiting for a test press in the mail. You’ve also got more input on what you’re listening to. The overall hands-on experience is a major improvement from what we’re used to dealing with.”

Goner still has ties with United Record Pressing, where most of the record jackets and labels from their earlier releases remain. But even with the relationship between Goner and United, Ives said the more releases they can give to Memphis Record Pressing, the better it is for all parties involved.

“Anything that we can do [at Goner] to help other local businesses stay afloat, we want to do,” Ives said.

“The local music industry used to be one of the biggest things in Memphis, and now it’s slowly building back up again. The pressing plant makes the local music infrastructure more complete, and I think everyone from show-goers, to local PR people, to the venues where bands play will feel the ripple effect.”