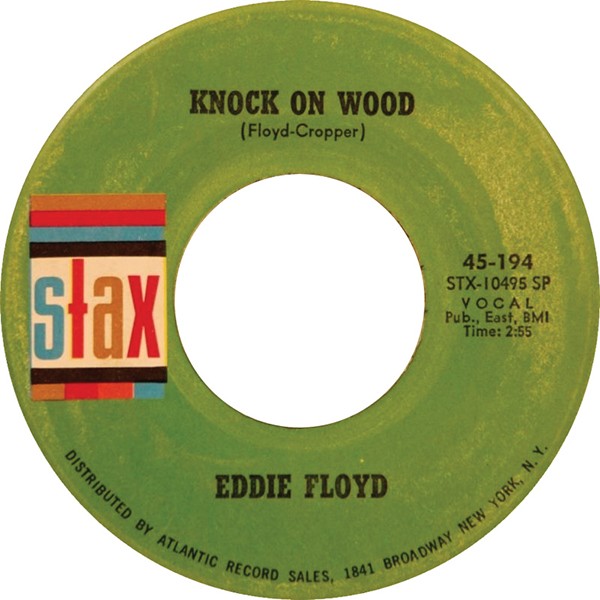

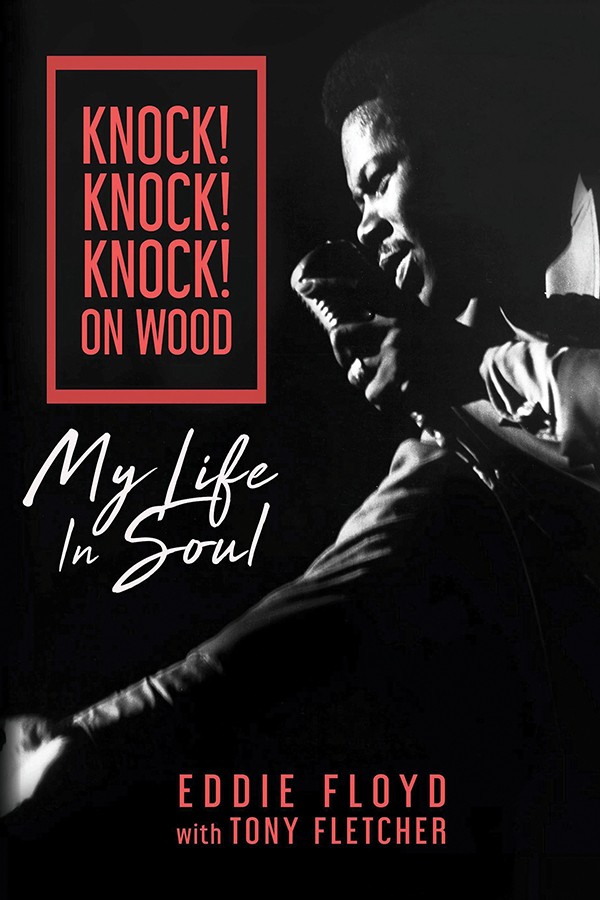

Eddie Floyd’s attitude is contagious. After speaking with him for over an hour, what stuck with me most was the laughter. It was a perfect foil to the doldrums of days without direction, to the dread of disease that colors all our lives now. The same good humor comes through in his voice, on such iconic tracks as “Knock On Wood,” “I’ve Never Found a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do),” and other stone classics from his time with Stax Records. As of this week, that humor can also be found in his new autobiography, Knock! Knock! Knock! On Wood: My Life in Soul (BMG, 302 pages), penned by Floyd and author Tony Fletcher.

Other salutary effects of the book spring from this good-natured disposition. His lack of grasping materialism is especially refreshing in these days of chicanery and corruption. “I got a badass Lincoln I bought with cash,” he writes in the final chapter, “Eddie’s Gone Shagging.” “But I ain’t driven it in eight years because I like to drive a truck! And people say, ‘Yeah but you could be more.’ And I always ask them, ‘What is more? … I’m happy with exactly what I’ve got.”

A corollary to this is his acknowledgement of those who’ve helped him. For this is an autobiography peppered with quotes from others — colleagues and collaborators like Steve Cropper, Booker T. Jones, Al Bell, and Carla Thomas. As he told me, “I thought, would it be okay if I did a book? I don’t know if I’m worthy of a book, but if I did one, it’s gotta be on the positive. And so Tony Fletcher, who helped me put it together, he got the names of all the different people in Memphis, and they were willing to be in the book and talk. And I didn’t know all these people felt this way about me. I’ve got so many people I’ve gotta thank for that.”

Still, as illuminating as his new book may be, I wasn’t prepared for the additional revelations and insights that came out as he spoke to me from his home in Alabama, near his hometown of Montgomery. He fleshed out the book’s details with still more observations on his life: learning music at Alabama’s Mount Meigs juvenile correctional center, his early days with R&B legends The Falcons in Detroit, his Stax years, and more. Through all these chapters run the common threads of writing and singing songs, which he continues to do to this day, a songwriter’s songwriter, no matter where he may find himself.

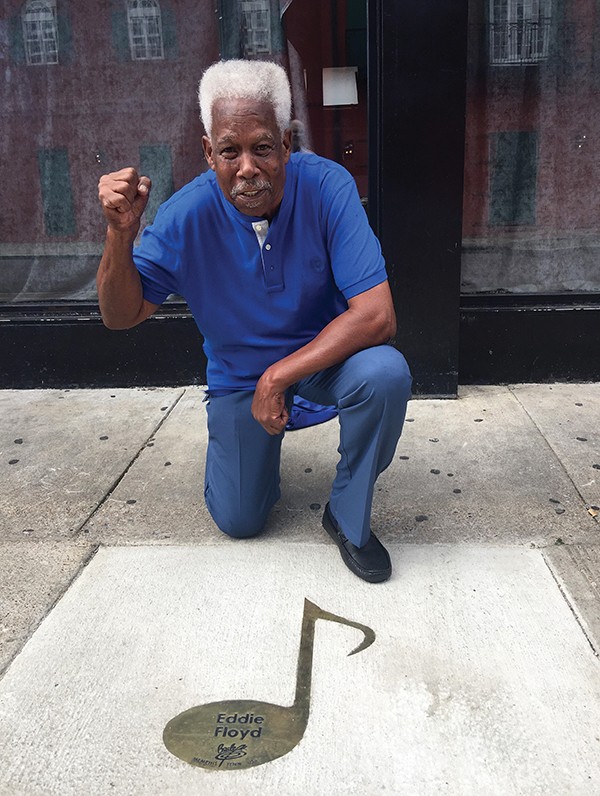

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Eddie Floyd was recognized on the Beale Street Brass Note Walk of Fame in 2016.

Memphis Flyer: You’ve moved around some, I’d say.

Eddie Floyd: Yeah, pretty much all my life. I started out in Detroit, Michigan, at 13 years old. And I wanted to be in a doo-wop group back during that time, so I formed the group The Falcons at 16 years old. I’ve been traveling ever since. I did record in Detroit with The Falcons. And then went on to Washington, D.C., where I met Alvertis Isbell [aka Al Bell], a disc jockey who was from Memphis. Carla Thomas was there, going to Howard University. And we kinda got together. Well, I was writing songs all the time, and I realized that Alvertis wrote songs also, so we got a chance to write a couple of songs for Carla during that time, when I first met her. That was my introduction to Memphis.

How much writing did you do with the Falcons?

Well, the two hits were by Lance Finnie and Willie Schofield. Schofield was the bass singer. He played piano; Lance Finnie played guitar. So they were the two to write the two hits that we had, “You’re So Fine” and “I Found a Love.” But there are quite a few ballads that I wrote. I wrote mostly all of the songs, if you could go back to the albums. But didn’t write the hits.

Is that you singing on “Oh Baby”? With that nice falsetto? That’s an amazing performance.

Yeah, that’s basically what I wanted to do. Joe Stubbs, his voice was quite different, and he did the real uptempos. Wilson Pickett came into the group after Joe left, and did “I Found a Love,” which was a ballad. Ballads were always my favorite. I liked the falsetto during that particular time, especially with your doo-wop groups. But as far as actually learning how to sing, I learned all registers, and I could sing all registers. I could sing the deep bass, or I could go all the way up to soprano.

You write that you owe a lot to the music director at Mount Meigs.

Mount Meigs Industrial School, where I was at for three years, Mr. Arthur Wilmer was the music instructor. He also had a jazz band during that time, the Cherokees, locally in Alabama. And he taught me theory, as far as all the registers to sing. And we had a choir. I sung second tenor, sometimes first. During the rehearsals, we had girls in the group also. I would always sing along with them, too. And that’s been my success as far as writing songs, and when I put a song together: I can hear all the parts that I actually wanna put in there. And actually sing them.

But of course, I went off to Memphis with Al Bell to do Carla Thomas’ two songs, “Stop! Look at What You’re Doing” and one called “Comfort Me.” I didn’t get the chance to do backgrounds behind them, but I would have been ready [laughs].

You write about not having grown up singing in church, like so many soul artists, but it seems that Mount Meigs choir had a lot of the that gospel element. Is that correct?

Oh, definitely. Of course we did classical songs also, with Mr. Wilmer, because he was a jazz band leader. And he would give us different classical songs, too. Not necessarily gospel songs. But, as a child, back earlier in Detroit, I used to go to the theater and see Lena Horne, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstine, all of ’em. And really when I write, it may come out that way. I mean, I don’t like one particular style of music. What comes to my mind is what I write.

I guess that keeps things fresh.

Yeah, well, I just like the challenge [laughs]. You know — some time uptown, some time downtown. The way I feel about it. And going to Memphis, well hey, the R&B scene. The Falcons, they said we were the first R&B group, basically. And so it kinda fit when I went to Memphis, because it had that R&B sound, and I was able to, right away, come up with different songs. I wrote with Steve Cropper first, you know, and then on to Booker T. And Al Bell, we wrote in Washington, D.C., and in Memphis. We did one good tune, “I’ve Never Found a Girl,” along with Booker, which was a good ballad also. So there I was still in ballads. And then I did “California Girl” with Booker also. But with Steve, we kinda went uptempo, and we came up with quite a few uptempo songs.

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Courtesy of Eddie Floyd

Eddie Floyd (left), Myrlie Evers-Williams, and William Bell at the Medgar Evers Memorial Festival in 1973

Very versatile! You write that in the days of the Falcons, you and the others didn’t think about hits, you just wanted a good song, a good track.

Oh yeah, we never spoke that way, as far as what was gonna be a hit. That was the beginning of an era of music, and everybody was involved. Everybody was into it and they all just wanted to write a song. We would actually see some of the songs become hits, but still didn’t speak of it that way. Like, ‘Oh wow, he’s got a hit, this number [on the charts].’ Well, we never would know what our number was, No. 2, No. 1, anything like that. That was years later. But going down to Memphis, everything changed. When we wrote a song, we did say ‘that’s a hit!’ many, many, times in the studio on McLemore Street. We knew when we were putting the song together. We knew. Everybody could feel it. And I guess that’s why it really did work.

Even when the people at Stax were conscious of hits, it seems like creating a song that stood on its own was the main thing.

Yeah, well, this is true. Everybody contributed to each song, no matter what song it was. Steve [Cropper] and I brought “Knock On Wood” in, and as we introduced it to the MGs, Donald Duck Dunn played this little bass line, and we didn’t tell him what to play. He played his own thing. I would say it wouldn’t have been a hit unless Al Jackson wanted to put a break in that particular song. He said, ‘Wait just a minute, let me put in a little stomp!’ ‘I better knock,’ boom boom boom boom. Stop. ‘On wood.’ Back to the rhythm. I remember Isaac Hayes in that particular song played the little bridge part of it. And we had never heard a bridge like that before [laughs].

I love your description of that recording and all the details of the teamwork that made it gel.

Well, that was true for just about every writer [at Stax]. Every song was really a family affair. If I could put it that way. Everybody contributed to every song, it didn’t make any difference. Even backgrounds. I would sing on somebody else’s song, if I’m there at the studio at the time. And they would do the same thing for me.

Does it still feel like a family when Stax folks get together?

Yeah! It’s just unfortunate that we’ve lost so many of our family members. But of course, Booker T., myself, William Bell, Deanie Parker, maybe Mavis Staples when she comes, and definitely Carla Thomas, ’cause she’s my favorite. And the groups there, too. The Temprees and others. Not leaving them out! When I first came to Memphis, and coming from a doo-wop group, I was actually more involved with those groups, because they were groups.

Like the Mad Lads?

Yeah! My favorite. Yeah, all of them.

It’s interesting that you were one of the first to embrace reggae, during the Stax years. Like that track you recorded with Byron Lee and his band, in 1971.

The reggae song? “Baby Lay Your Head Down (Gently on My Bed).” Actually, we went down to Kingston — Al Bell, Jim Stewart, and the MGs. They were doing a distributing deal. We knew about all the guys over there playing the music, too. Of course, we were gonna meet a lot of ’em. Byron Lee, who was the biggest music there at that time, we went to his studio. And actually, none of the MGs played on that record at that time. We wanted to get the guys from Kingston to play it, you know? Little guitar player come down the road, and he don’t even have a case for his guitar. He’s got it on his shoulder, walking. But when he got in the studio and started playing, man! Wow. So we come up with two or three songs and got back to Memphis, and then the MGs did the overdubs on those songs. I have three or four records that have probably never been hits over here, one called “Consider Me,” but in the islands, man, they’ve been No. 1 for over 30 years at least. Every time I go down there it’s just amazing.

It’s a beautiful thing, these little regional markets where you can have a hit, like the Carolina beach scene you write about, or Jamaica. Or the UK, where so many songs have taken on a new life.

Oh yeah. And Northern Soul in England. They’ll listen right away. And I know all the fields. That’s the way I write, too. Sometimes I’ll be thinking about them also. Definitely Northern Soul. You can do different styles, if you have an idea. ‘Cause they’re open-minded there! If it’s got a groove, they’ll get into it. You can introduce some new things to ’em, so they’ll be eager for new grooves. It’s an amazing area.

I was wondering how well some of your more recent records have done in some of these alternative scenes, like Northern Soul. Has your recent stuff had an impact?

I could write a song 30 years ago and then get an idea today, and it might sound like the one that was 30 years ago. I just keep that same concept, and that’s the way it comes out with me when I write. I’m beginning to find that a lot of the young kids are beginning to pick up a lot of my songs. “I’ve Never Found a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do)” and “Big Bird.” Those are two where I’ve had many young groups hit me up and say, ‘Listen to our version. We’re gonna put it out.’ [laughs] Well, you’re gonna have to contact some people to make sure it’s legal! And a couple actually took off.

You were here for the groundbreaking of the Stax Music Academy 20 years ago and have been closely associated with them. Do you get to Memphis often?

I’m in Memphis all the time. And I’ll get with different artists. Lester Snell is my favorite keyboard man; he was with Isaac [Hayes]. I was there three weeks ago and did a song for the Blues Brothers Band in New York. Dan Aykroyd’s band. “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love.” I went in with Lester and put the vocal down. Lester played the whole track, and I came back home and did a video of it, sent it to the Blues Brothers, and they’re at the moment putting all the other guys on the video. They wanted to do something for the virus, you know, to kinda inspire people and all. So that all came out of Memphis.

I spent a lot of time on the road with the Blues Brothers and Steve [Cropper]. One time we were in Canada doing a thing about Stax, and Steve invited me to come out and be a special guest, and it ended up being 22 years [laughs]. It was all right with me. It was family!

At 83, it seems you aren’t slowing down a bit. You released an album on the revived Stax label in 2008, and you still work with the Blues Brothers Band. What’s the future have in store?

There’s other stuff I did with Lester that will come out under my name. You know, I’ve played with him so many years. Like I said, I never really stopped, so, one more! Let’s try one more album. Then there’s Mike Stewart, who used to be in Atlanta with William Bell but he’s now in Nashville. I’ll go up to his place and do part of that same album. It just all depends on this virus. But at least we got each other! [laughs] Yeah, we have. I will never stop the music. I’ll put it to you this way, the way I tell everybody: I’ll rock ’til I drop. That’s it.

Piper Ferguson

Piper Ferguson

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum