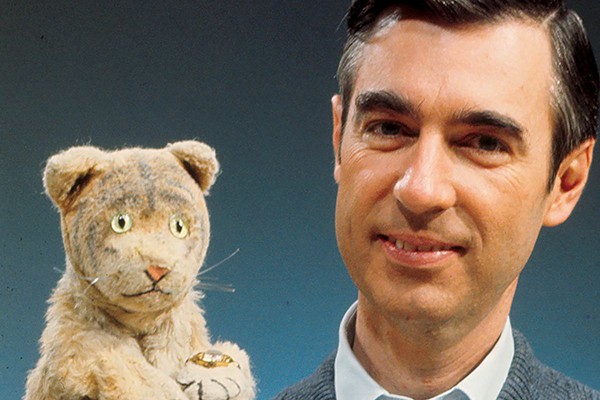

Before he became Academy Award-Winning Director Barry Jenkins, the filmmaker brought his debut Medicine for Melancholy to Indie Memphis in 2008. He’s always kept in touch with his indie film roots, even after winning the Best Picture Oscar for 2016’s Moonlight. In 2019, he served as a judge for the Indie Memphis Black Filmmaker Residency for Screenwriting. “I enjoyed the process so much that I thought that there should be two grants, one for someone who’s not Memphian, and then also for someone local. So I matched the grant that Indie Memphis was offering.”

The project that got Jenkins’ nod for the residency was All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt by Raven Jackson. “It was a bunch of proposals,” says Jenkins, but what caught his eye about this one was the originality of the vision. “Usually, people create a ‘lookbook,’ and that lookbook or mood board has all these images of things that they didn’t create. It’s like, I’ll take an image from this film, or an image from this fashion spread, or the image from this sort of photographer’s work. It was clear that Raven’s mood board, her pitch deck, was all her own imagery, which I thought was really cool. You could see very clearly what her aesthetic was, and she spoke about how she saw the film, how the film would feel … She just had a very clear voice, and with the material she provided it was very obvious she could back that voice up, that she could do what she said she was going to do.”

The Tennessee-born filmmaker spent two months in Memphis finishing the screenplay before shopping it to Hollywood producers. “Raven had her pick of outfits she could have gone with,” Jenkins says. “It was a very competitive situation between A24 and a couple other companies to finance the script,” he recalls. “The script came back to me, not through Indie Memphis, but through very professional channels, because people were reading it once Raven had completed the script. So, shout out to the Indie Memphis residency. It certainly was good for her! People were talking about how it was unlike anything they had ever read. And then once I read it, I was like, ‘Oh yeah, this is really damn cool. Let’s knock on Raven Jackson’s door again and figure out if there’s a way to help her make this film.”

Jenkins’ production company Pastel produced the film along with A24, filming the bulk of it near Jackson, Mississippi. “Some of her [Raven’s] lineage is from Mississippi, and there were a few locations that she specifically was interested in, and things that she had seen in imagery from her childhood. There were churches that she had read about that were in the Jackson area in Mississippi, and they were still there and still existed. Organically, the film sort of rooted itself in Mississippi.”

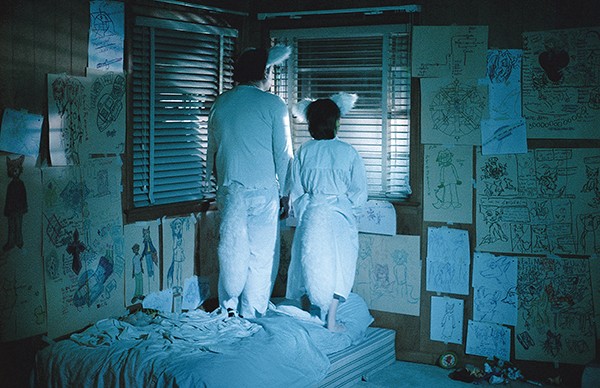

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt premiered last January at Sundance. It comes full circle as the opening night film of Indie Memphis 2023. “I think people are kind of just in awe of how tactile the film is,” says Jenkins. “It ignites your senses, which is crazy, because you’re watching these images projected on a flat screen in a theater, and yet they feel three-dimensional. You can tell it’s that Southern light, but also in the sounds, the movie really envelopes people. There’s a very standardized way that we become accustomed to watching television and watching movies, and the films have a certain rhythm and a certain logic. Raven has created this thing with a logic that doesn’t have any fidelity to any of those things. I think when people see the film for the first time, it’s a very unique experience, is what I’ll say. There are some people who grew up in regions like this, the one depicted in the film, who do feel like they’re taken home. And then there are other people for whom this world is completely alien, and they feel like they’ve been invited to a place, immersed in someone’s very real memories of what it’s like to be a young Black woman growing up in the American South.”

All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt screens at Crosstown Theater on Tuesday, October 24, 2023 at 6:30 p.m. as the opening night film of the 26th annual Indie Memphis Film Festival.