Sly Stone performs at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival in Summer of Soul.

For me, day 3 of Sundance was a more indoor affair.

The drive-in is great, except in the wind and rain. So when the weather decided not to cooperate, my wife and I decided to stick to streaming. It turned into a pretty epic binge day that resembled the analog festival experience’s rush from screening to screening.

We started off with the film that was, for many, the most anticipated of the festival. Summer of Soul (… or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), which opened the live-premiere streaming offerings on Thursday, is a music documentary directed by Amir “Questlove” Thompson, better known as the drummer for The Roots and bandleader on

Questlove and his producers found out 12 years ago about a forgotten stash of footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. In the months before Woodstock, the free music festival ran for several weekends in a New York park, attracting some of the greatest Black musicians of the time, including Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, The Fifth Dimension, and Gladys Knight and The Pips. The Memphis area was very well represented, with B.B. King, Mississippi’s Chambers Brothers, and The Staple Singers. Hundreds of thousands of people attended the concert series and the show was professionally recorded and taped by a four-camera crew with the intent to make a television special out of it. But the TV show never materialized, and the 45 hours of footage sat in a producer’s basement for 50 years. Thompson and his team transferred and restored the tapes, and secured interviews with many of the surviving musicians and audience members, for whom the forgotten show seemed like a distant dream.

Thompson was introduced by festival director Tabitha Jackson as a first time filmmaker, which is true enough. Breaking new talent is what the film festival is all about. But Thompson had an advantage over the normal first time director, in that he is a relentlessly omnivorous music scholar and author, which gave him the intellectual discipline to do the research and make Summer of Soul more than just a concert film. But most importantly, Questlove is a DJ who grew up obsessively making mix tapes. Those are the skills which served him best in the editing room, as he chose the best musical moments from the concert series and put them the right order.

The performances captured on the moldering tapes are spectacular. The film opens with Stevie Wonder abandoning his keyboards and taking to the drums. Did you know Stevie was a kickass drummer? Neither did I. B.B. King is captured at the top of his game. The Chambers Brothers reveal a deep, jammy groove beyond their hit “Time Has Come Today.” Thompson puts each performance in context, such as when Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis, Jr. tell the story of how they came to record “Aquarius/Let The Sun Shine In” from Hair, as their younger selves sing and dance up a storm onscreen.

The highlight of a film full of highlights is an emotional, impromptu duet between Mavis Staples and her idol Mahalia Jackson of “Take My Hand Precious Lord.” Jesse Jackson introduces the song, telling the story of how he was on the balcony at the Lorraine Motel when Martin Luther King, Jr. asked bandleader Ben Branch to play the song for him moments before the civil rights leader was assassinated. As the band swells, an emotional Mahalia Jackson pulled Mavis Staples from her seat and put the microphone in her hand. Stunned at the anointment by the gospel legend, Staples takes center stage and lifts off in what she called the most memorable performance of her life. Then, Jackson takes the second verse and turns it into a wail of mourning and declaration of Black power.

Summer of Soul is an instant classic that delivers both goosebump-filled musical moments and a clear and well-organized history of a pivotal cultural moment that was almost lost to time.

‘LATA’

Short film programs are always my favorite part of any festival experience, and the 50 or so shorts strung across seven programs feature some real gems, proving that the pandemic couldn’t hold back the creativity. Andrew Norman Wilson’s “In The Air Tonight” uses altered stock footage and killer sound design to retell the urban legend behind Phil Collins’ 1980 hit song. He put it together in his apartment during quarantine. Alisha Tejpal’s excellent and moving “LATA” is a naturalistic examination of the life of a domestic worker in India that bears the meditative stamp of Chantal Akerman’s Hotel Monterey. Joe Campa’s animated short “Ghost Dogs,” in which the new family pet can see the apparitions of all the dogs who have lived in the house, veers between funny and unexpectedly poignant.

Looking for love in ‘Searchers’

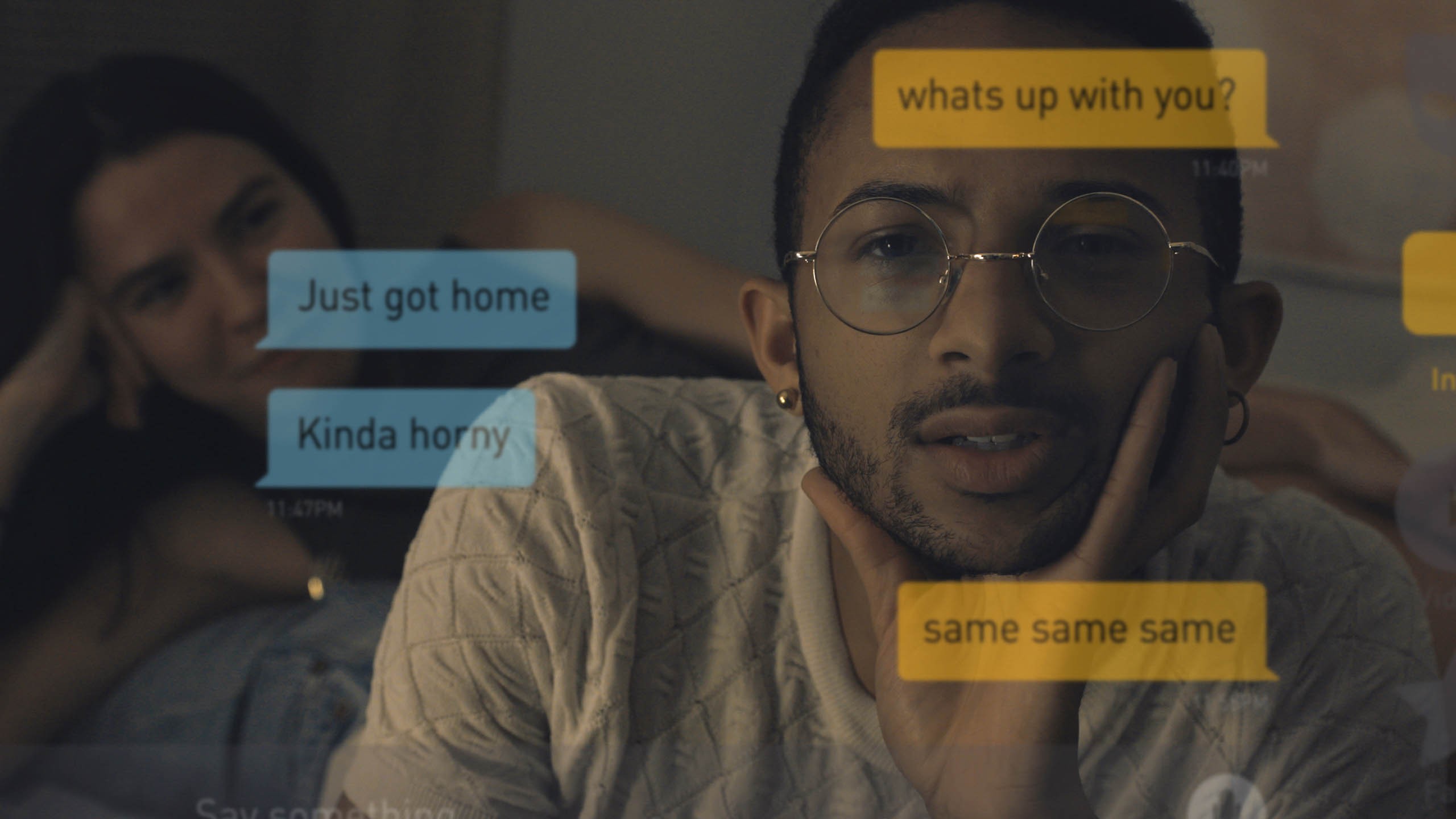

The second feature documentary of the day was Pacha Velez’s Searchers, an intimate and often hilarious look at dating online. Velez films dozens of different people as they swipe through their choices on dating apps, and interviews them about their experiences. In a couple of cases, his subjects turn the tables on their interviewer, and Velez reveals his motivations stem from his own experiences as a single guy who just turned 40. Shades of Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March appear as Velez takes his own dating app test with his mother at his side. The innovative and insightful documentary starts off unassuming, then subtly worms its way into your brain. With subjects ranging from ages 19 to 88, Searchers reveals dating apps as the great equalizer of our age.

All Light, Everywhere

Tonight, the weather outlook at the Malco Summer Drive-In is much improved. The first show is Theo Anthony’s All Light, Everywhere. Using quantum theory’s spooky observer effect as its jumping off point, this essay film travels the blurred line between what we call “objective reality” and the often flawed assumptions that undergird our understanding of it.

The second show is the sci-fi feature Mayday by Karen Cinorre. Grace Van Patten stars as Ana, a woman from our reality who is transported into another dimension where a group of women soldiers are fighting an endless war whose origins they barely understand. The fascinating-looking Mayday is billed as the first feminist war film.

Sundance in Memphis: A Soul Explosion and All Light, Everywhere

You can buy tickets for the Malco Summer Drive-in screenings of Sundance films at the Indie Memphis website.

Dan Wireman

Dan Wireman

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks