On the constellation of Memphis music attractions, the Smithsonian Rock ‘n’ Soul Museum doesn’t burn quite as bright as Graceland, Sun Studio, or the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. But since its founding more than a decade ago, the museum has served a useful purpose in pulling the different strands of the Memphis music story into one narrative.

This month, with the launch of the first Memphis Music Hall of Fame, Rock ‘n’ Soul steps into the spotlight.

The general idea of a Memphis-specific Hall of Fame has been in the air for decades, but the current realization — with an inaugural class of 25 inductees that was announced last month and will be feted at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts next week — has its origins in a Rock ‘n’ Soul Museum strategic planning meeting roughly seven years ago.

The museum had incurred debt in its original setup at the Gibson Guitar Factory and then relocation costs when it moved to its current home at FedExForum. It took awhile to get those issues under control.

“As we were feeling like our head was coming above water, we were able to really focus on what is our mission,” says museum executive director John Doyle. “And we felt like this was something that’s an extension of our mission to preserve and tell the story of Memphis music and to perpetuate its legacy.”

Kevin Kane, the head of the Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau, who also serves as the chairman of the Rock ‘n’ Soul board, was a big proponent of the project.

“This should have happened 20 years ago. If any city deserves it, it’s Memphis,” Kane says. “We felt like we were the obvious entity to do this. Us or the Music Commission or Music Foundation. It makes sense for it to be us. We’re that portal to tell an overarching story that transcends Sun, Stax, etc. And we have a facility, unlike the commission or foundation. People walk through on a daily basis. We have a footprint.”

Doyle says he and the museum’s planning committee consulted other music attractions in town before launching the project.

“We wanted to make sure it wasn’t a faux pas to do this,” he says. “No one was biting at the bullet to do this because it takes a lot of work, and it takes a lot of money to do it right. We felt like we were the people to do it, because we tell the complete Memphis music story. But we’re not looking to pound our chest and say Rock ‘n’ Soul’s doing this. We think it’s something that’s right for the city.”

The Parlor Game

In order to make this idea a reality, Doyle assembled a 12-member nominating committee of music professionals only partly rooted in Memphis, a group that included, among others, authors Peter Guralnick and Nelson George, former Commercial Appeal music critics Larry Nager and Bill Ellis, former executive director of the national Rhythm & Blues Foundation Patricia Wilson Aden, and former Smithsonian curator and Southern historian Pete Daniel.

This May, on the weekend of the annual Blues Music Awards, Doyle brought most of the group to Memphis for a two-day session in a suite at FedExForum, where, facilitated by the Recording Academy’s Jon Hornyak and former Stax Museum director Deanie Parker, they came up with the first class of inductees for the first Memphis Music Hall of Fame.

It was the best Memphis music parlor game ever, with, after several rounds of initial nominations, 52 names arranged on a wall, whittled down to an inaugural class (see sidebar on p. 21) after two days of deliberations.

“We limited it to 25, which was more than we’ll do in other classes,” says longtime journalist and music-industry executive David Less, who was on the nominating committee and in the room for live deliberations. “We may do five names next year, but if you do five in the first year you don’t really have a hall of fame. You just have five guys. So we wanted to frontload it a little, but we didn’t want to say here’s everybody.”

“They wanted to know from the planning committee standpoint what we wanted from them,” Doyle says of the process. “Their first question was, Do you want the expected list of nominees? And I said I want what you consider the right list of nominees.”

There were no longevity guidelines. No “birth requirement.” No separate categories for non-performers.

“We set all of that aside,” Doyle says.

The class of inductees that emerged included obvious names (Elvis Presley, W.C. Handy), obscure names (Lucie Campbell, William T. McDaniel), and controversial names (Three 6 Mafia, ZZ Top). With the knowledge that this is meant to be an ongoing process, the group produced a representative list of key players in Memphis music history rather than 25 definitive names.

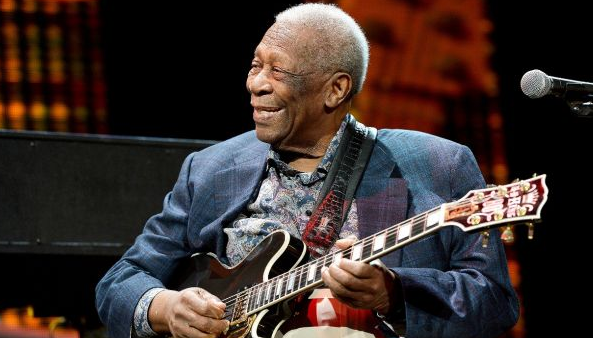

“We went around the group once and had everybody nominate somebody and observed that no one picked the four people we all knew other people would pick,” Less says. “No one wanted to waste their vote on Elvis or Sam Phillips or W.C. Handy or B.B. King. So after the first round we just said, these four people, let’s put them up there. We know they’re going to be there, so that frees us all up and we don’t have to talk about them anymore. We all agreed that those would be the ones who in any scenario had to be there.”

“Some of the big names on that inaugural list are there because they’re the biggest names,” says Ellis, who wasn’t in town for the meeting but contributed via e-mail and conference call. “But then outside of that is where we all sort of bring our own perspectives and fight for somebody, like a Jimmie Lunceford or a Lucie Campbell or even a Memphis Minnie, who was as important a blues pioneer as Muddy Waters in a way.”

Ellis pushed for gospel pioneer Campbell, while both he and George made a case for Three 6 Mafia, the youngest inductees. Less was a booster for jazz sideman George Coleman and educator William T. McDaniel.

“Music is more than just the stars, right? It’s a collective achievement, especially in a place like Memphis, where so much of what’s happened of historical merit has happened outside the purview of the hits, and there have been plenty of those,” Ellis says. “But the chart and sales success doesn’t explain the significance of a Lucie Campbell or a W.T. McDaniel. I was thrilled to be involved if only to see Campbell and Three 6 Mafia make the inaugural inductee list, the past and the future broadly laid out there.”

“My feeling is that it’s pretty easy to go Elvis, B.B. King, Isaac Hayes,” George says of pushing for Three 6 Mafia. “But I wanted to embrace the panorama and have it not just be people from the ’50s. And the Mafia winning the Oscar, that was a historic event.”

The curious-to-some inclusion of ZZ Top also seemed to emanate from a desire for a more contemporary presence in the initial class of inductees.

“ZZ Top, in truth, kept Ardent Records alive,” Less says in defense of the choice. “All of their first records were recorded here. They lived here while they were recording. You can’t count Sam & Dave if you don’t count ZZ Top.”

No one thinks the list is perfect, of course. Not even members of the committee that made it.

“I nominated Carla Thomas, but we decided you can’t put Rufus and Carla in the same year,” says longtime Memphis broadcaster Henry Nelson. “But Carla’s gotta go in the second year.”

Ellis, for one, echoes the common refrain about Johnny Cash’s absence from the list.

“Johnny Cash?” Ellis asks, with a hint of incredulity. “I can’t speak for the committee, but he’ll be on the next list.”

“Where’s Johnny Cash? Where’s Justin Timberlake? Where’s Carl Perkins? That doesn’t mean we don’t think they’re great or they won’t be in a Memphis Music Hall of Fame,” Less says. “It’s just the first blush, it’s not the last look. It’s not a definitive list. Our charge was not to produce the obvious, definitive people.”

Follow Through

Starting a hall of fame and picking a list of inductees is one thing. Making something of it is another, and where exactly this endeavor heads is still somewhat unknown. A website, including inductee profiles written by nominating committee members Guralnick, Ellis, Nager, and Robert Gordon, launched when the inductees were announced last month.

Next week, an induction ceremony will be held at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, produced by Willy Bearden, who will try to tell the story of the 25 inductees in roughly two and a half hours, including a series of musical performances with a house band of ace Memphis session musicians backing some of the living inductees as well as some of their children and artists they’ve influenced.

“It’s a tough thing to do, but I think we’ve been able to approach this in a little different way,” Bearden says. “There won’t be people standing at a podium inducting people. I can guarantee that this is going to be a really good show.”

Some time next year, according to Doyle, the Rock ‘n’ Soul will open an interactive Memphis Music Hall of Fame exhibit inside the current museum, while Kane says the group is exploring other avenues for some kind of “external public tribute.”

Left open is the prospect of a more extensive physical space for a Memphis Music Hall of Fame, either on its own or as a component of a larger Rock ‘n’ Soul space, something of which nominating committee members seem to be in favor.

“If there’s a way to incorporate it into the Rock ‘n’ Soul, that would be great,” says Less, who helped with the Rock ‘n’ Soul Museum’s initial launch. “I’m a proponent of synergy. I don’t think you make people go to two locations for essentially the same thing. Rock ‘n’ Soul is a limited story of Memphis music. When we started it, we set the parameters of it with the Smithsonian, and I think it’s a definitive portrait of that time frame. I think the Memphis Music Hall of Fame expands that conversation a little bit, but why send people to two places?”

“Will it be a separate building? We think that’s something the community needs to decide more than us, but it’s definitely not something that needs to happen immediately,” Doyle says. “It’s usually a 10-year process, because you’ve got to have that many inductees in order for it to be a compelling exhibit. Plus, here in Memphis, you’ve got icon buildings such as Sun Studio, Graceland, Stax, as well as our own museum. So we don’t know that there’s a need for another building.”

“If it warrants it or the opportunity presents itself to open another facility, we’ll look at that,” Kane says. “We’re not married to anything. With technology, you don’t need [as much space].”

Whatever road this project takes, it’s already been a conversation-starter.

“The great thing about a hall of fame is that everybody wants it. The bad thing is you can never do it right,” says Doyle, who is already planning to reassemble his nominating committee next spring to select a new class of inductees. “People are so passionate about music. But this will be decades for us. Ten years from now, we’ll be inducting Grammy winners and chart toppers.”

Among the names mentioned by various committee members as potential future inductees are Cash, Thomas, Timberlake, Big Star, the Blackwood Brothers, the Memphis Jug Band, Chips Moman, and on and on.

“There are only a handful of cities that could do this,” Less says. “Chicago. Detroit. New York. Los Angeles.”

“It’s another piece to providing a sustainable identity of Memphis as a major music capital and not just for the tourists,” Ellis says. “But for those who live in the city and take great pride in being part of something much larger than themselves.”

First Class …

The 25 Inaugural Inductees to the Memphis Music Hall of Fame.

Jim Stewart & Estelle Axton

The brother/sister duo who put the “St” and “ax” in Stax as co-founders of the city’s signature soul label.

Bobby “Blue” Bland

The soul-blues titan who honed his craft alongside other future stars in the 1950s vocal group the Beale Streeters.

Booker T. & the MGs

The Stax house band and hitmakers-in-their-own-right who embodied one version of the Memphis sound.

Lucie Campbell

The gospel composer who was a contemporary of the more famous Thomas A. Dorsey and who helped shape the black gospel sound of the pre-soul era.

George Coleman

The Memphis jazz great who was a saxophone sideman for B.B. King before joining up with the Miles Davis Quintet.

Jim Dickinson

The producer/sideman/bandleader who was a musical sponge and bridge between distant eras of Memphis music.

Al Green

The last soul legend who was the purest Memphis vocalist since Elvis Presley — and remains productive.

W.C. Handy

The “Father of the Blues” whose published compositions popularized the regional form.

Isaac Hayes

A Hall of Famer even before Shaft and Hot Buttered Soul who evolved from essential sideman/songwriter to superstar.

Howlin’ Wolf

The Delta-bred blues powerhouse who cut classic sides with Sam Phillips before migrating north to Chicago.

B.B. King

The “Beale Street Blues Boy” who started his career on radio and on stage locally before becoming the blues’ biggest modern star.

Jerry Lee Lewis

The piano-pounding revolutionary who traveled up from Louisiana and was introduced to the world via Sam Phillips’ Sun label.

Jimmie Lunceford

The Manassas High School gym teacher who evolved into the King of Swing.

Prof. W.T. McDaniel

A segregation-era music teacher at Manassas and Booker T. Washington high schools who trained multiple generations of Memphis musicians.

Memphis Minnie

The “Queen of Country Blues” who first hit Beale Street as a young teen and emerged as one of the signature blues artists of her era.

Willie Mitchell

The bandleader and producer who forged the sophisticated Hi Records soul sound and “discovered” Al Green.

Dewey Phillips

The original wild man of rock-and-roll radio who gave Elvis Presley his first spin.

Sam Phillips

The idiosyncratic producer and Sun Records founder who cut classic blues sides and then presided over the great wedding ceremony, marrying country and blues to create rock-and-roll.

Elvis Presley

The kid from Tupelo who waltzed into Sun Records and announced that he sang all kinds. Perhaps you’ve heard of him.

Otis Redding

The soul man supreme who gave Stax Records its first true superstar and then left us too soon.

The Staple Singers

The family band who blended soul and country, gospel and blues into a distinctive sound — and had something to say.

Rufus Thomas

The prankster, patriarch, and pop-cultural preacher who drove Memphis music from the Rabbit Foot Minstrels to WattStax.

Three 6 Mafia

The Southern rap pioneers who graduated from selling self-made mixes out of their trunk to claiming Oscar gold on behalf of crunk.

Nat D. Williams

The “Beale Streeter by birth” who took the mic at WDIA to become the first black disc jockey on the country’s first all-African-American radio station.

ZZ Top

The dusty Texas blues band that honed its sound and emerged as superstars out of Memphis’ Ardent Studios.

The Memphis Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony

Cannon Center for the Performing Arts

Thursday, November 29th • 7 p.m.

Tickets are $100, $50, or $30.

memphismusichalloffame.com

Alaina Getzenberg

Alaina Getzenberg

Randy Miramontez | Dreamstime.com

Randy Miramontez | Dreamstime.com