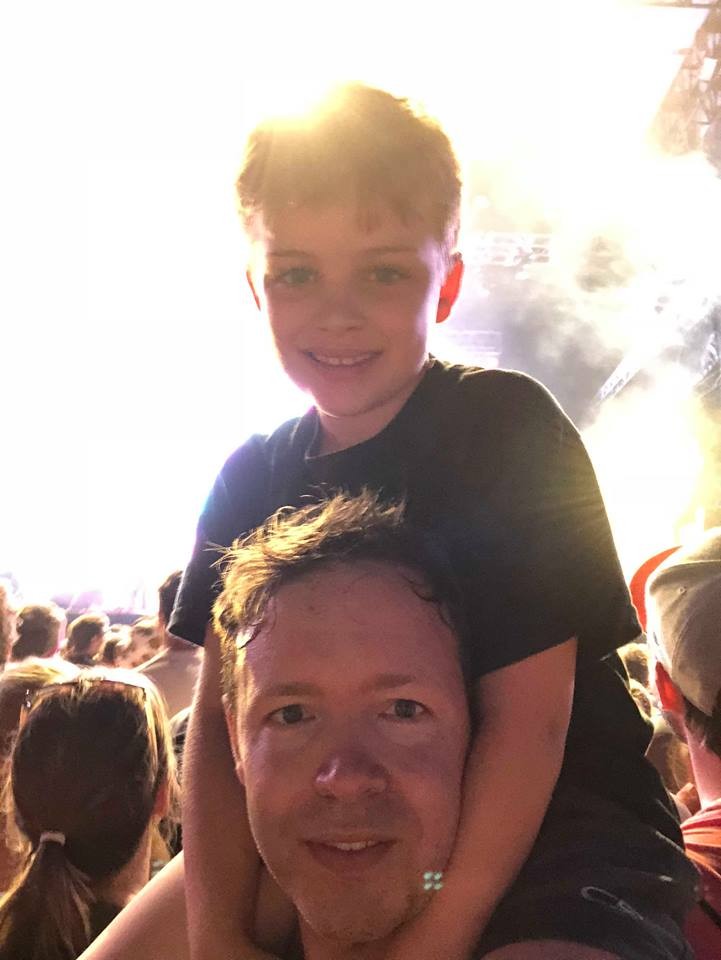

The Flaming Lips

Working for 35 years with a family vibe and a DIY attitude.

by Alex Greene

“We A Family.” So proclaim the Flaming Lips in last year’s single and closing track on the Oczy Mlody album. And though it’s a cliche that many a rock band pays lip service to, it’s another matter to see one that puts the idea into practice with such creative dividends. The Lips, as they are affectionately known, have made the family vibe work for them, having performed and recorded for 35 years. And while some associate family bonds with complacency, the Lips have benefited from an opposite effect: a free-ranging creativity fostered by enthusiastic collaboration.

To singer and songwriter Wayne Coyne, playing well with others is key. “Music especially is really made from collaboration,” he muses. “I can imagine the very first music that was ever made was someone hitting this rock over here, and someone hitting some tree stump over there, and they’re like, ‘Hey, if we work together, we could get something good going.'”

The Lips have taken collaboration to greater creative heights than most. Who would have guessed, for example, that this tight-knit family, these kings of alt-rock, would team up with megastar Miley Cyrus as the Dead Petz? Or, having done that, that they’d invite her into their world for the aforementioned single? Who, for that matter, could have guessed that after a good decade of rising on the college radio charts, they would sweep away their established rock sound in favor of the haunting orchestral atmospheres of 1999’s The Soft Bulletin? Given their ongoing quest for new musical territories, it’s clear that this is more the Swiss Family Robinson than Archie Bunker.

Memphian Jake Ingalls knows this as well as anyone. “It’s a big family vibe,” he notes. As a musician attending the University of Memphis, he had little inkling that an afternoon volunteering on the Lips’ stage crew in 2009 would lead to a position as a roadie and guitar tech. Or that, three years later, the unthinkable would happen: “I got a call from Wayne and he said, ‘Can you keep a beat?’ I said, ‘I like to think so. I’m in my own band.’ He said, ‘All right, well, we’re about to play all of Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots at South by Southwest. We wanna make it special, with extra musicians and no backing tracks. So let’s just say, you need to be in Oklahoma tomorrow for rehearsal.'”

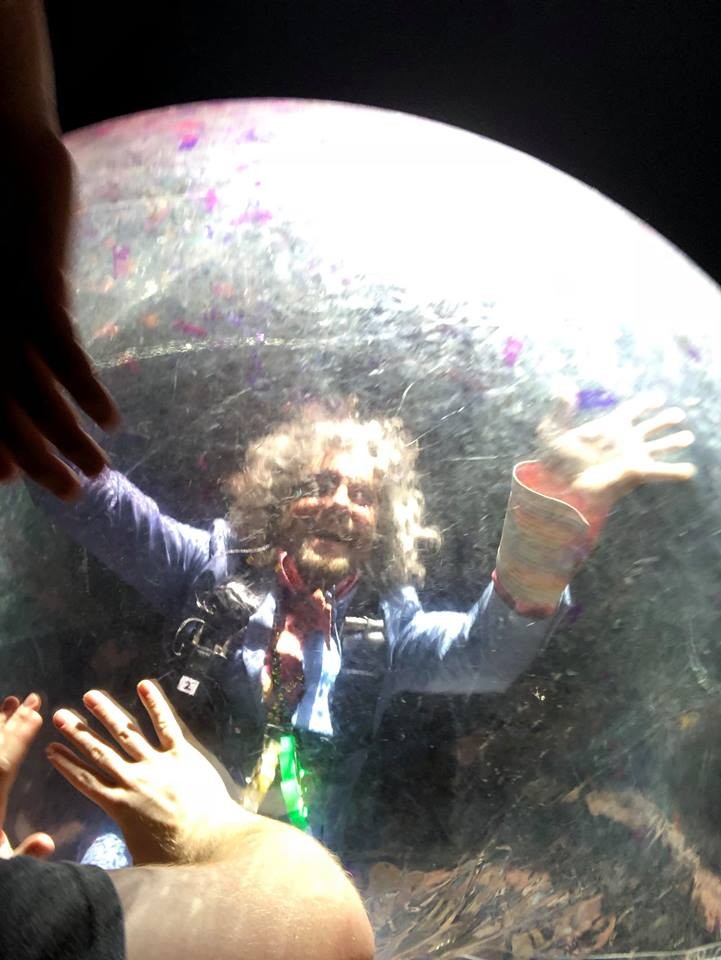

Ingalls notes that the band thrives on a “Hey, gang, let’s put on a show!” esprit de corps. Referring to their visually outlandish stage shows, he says, “A lot of people in Memphis, and a lot of people like me, identify with the band as a bunch of regular people who are trying to put together a truly fantastic production. So in a way it tricks people into thinking they’re bigger than they are. When you get up close to the stuff, you see that when Wayne pulls out these giant foam hands that shoot lasers out of them, it’s not something that he ordered in New York. They made the giant foam hands, you know? And put the lasers in there themselves. If a giant inflatable butterfly rips, you freaking repair it with duct tape.”

This DIY attitude is likely due to the Flaming Lips’ roots in Norman, Oklahoma, where they were blissfully ignorant of musical trends, and being resourceful was key. Coyne and his brother founded the group as an extension of like-minded friends hungry for extreme thrills, “the Fearless Freaks.” While Coyne’s brother soon left the band, original bassist Michael Ivins is still with them. Steven Drozd joined in the early ’90s when an earlier drummer quit, and the three of them have been the steadfast core of the band ever since.

All the while, they’ve doggedly avoided current trends. In Oklahoma, Coyne recalls, “We didn’t really know what was cool, what was old, and what should be embarrassing. Early on, in San Francisco, we opened up for the Jesus and Mary Chain. And we played ‘Wish You Were Here’ by Pink Floyd!” Some may have considered it a betrayal of the post-punk aesthetic, but “if we like it, we really don’t care. Sometimes there’s just no way of knowing what’s cool and what isn’t. And to follow your heart and do what you love is probably gonna serve you better. ‘Cause what’s cool is changing all the time.”

Such an attitude, borne of life in the hinterlands, was clear early in the band’s life. In the 1987 track, “Everything’s Explodin’,” Coyne sings “If you don’t like it, write your own song,” and in a sense, it’s the band’s manifesto. Perhaps that maverick spirit has been nurtured by remaining in their hometown. Coyne still lives in the neighborhood where he grew up, and from that secure base, the band has kept evolving, as is apparent in their soon-to-be-released Greatest Hits, Vol. 1. When the sea change of The Soft Bulletin heralded a new cinematic sweep in their sound, they morphed as a live band by using pre-recorded backing tracks. But in recent years they’ve pivoted yet again, back to a bigger band of live musicians. Now, the whole “family” fuels the band’s creativity.

As Ingalls says, “With the Lips, you can be as involved or as not-involved as you want. But it’s rare that anything that you come up with is going to come out exactly the way you put it in. Wayne might say ‘What would you sing here?’ and I’ll sing something. Then I’ll go off for a month with [Ingalls’ band] Spaceface and come back, and that vocal melody has suddenly turned into a keyboard part. Or vice versa.”

For Coyne, it’s the surprises, and even the mistakes, that make it worth doing. “Boredom, for an artist, is the worst thing that can happen. So that energy you get from being excited about this thing that you’re about to do, that enthusiasm, for us, that’s very contagious. To be creating something together when that breakthrough happens, that’s the thing. Our manager has always been on the side of ‘Do your thing, and let’s make that work,’ as opposed to ‘Let’s figure out what works, and the Flaming Lips can go along with it.’ No, do your thing. I guess we’ve just been lucky that we’ve attracted these people, like Jake, that are like-minded and wanna work the same way. We’ve just been lucky to keep evolving, to keep trying again, and keep discovering new things.”

The Flaming Lips play the Beale Street Music Festival’s FedEx Stage on May 6th, at 7:40 p.m. Ingalls’ band, Spaceface, will play Railgarten on May 19th.

…

Valerie June

Valerie June

Around the world and back home again.

by Chris McCoy

Memphis is a city of musicians, each with their own stories of tragedy, triumph, or something in between. But has there been a Memphis music story in the last decade more satisfying than Valerie June’s rise to stardom?

Growing up in Humbolt, Tennessee, Valerie June learned to sing in church. Her father Emerson Hockett was a music promoter, and her brother Patrick Emory is also a musician. She moved to Memphis around 2000 with her then-husband and played in a folk duo called Bella Sun. After her marriage ended, she became a fixture in the Midtown music scene as a solo artist.

For years, she worked all day cleaning houses or at Overton Square’s landmark hippie shop Maggie’s Pharm, then put in long nights playing guitar and singing at places like Java Cabana. She fostered a knack for collaboration with local folkies such as the Broken String Collective, which served her well when she recorded her debut solo album, and she was one of the musicians featured on Craig Brewer’s pioneering streaming series, $5 Cover.

Then, in 2011, after raising money for her a new album on Kickstarter, she moved to Brooklyn. There, she met Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys, who produced her breakthrough album Pushin’ Against A Stone.

They say fortune favors the prepared, and Valerie June was ready to take her shot when opportunity struck. From the opening “Working Woman Blues,” which combined autobiographical lyrics about struggling to make it on her own with a haunting groove, to the smooth girl-group pop of “The Hours,” the record cast a powerful spell. After a stint touring with Sharon Jones, her next album, 2017’s The Order of Time, saw June emerge as more assured band leader. The explosive mix of funk and hill-country drone in “Shakedown” propelled her to international recognition and a world tour that shows little sign of slowing down.

“I went everywhere, so many places I had never been before, like Quebec City, Japan, Australia. This world is huge!” she says. “The highlight was Hawaii. I’ve never seen so much beauty in my whole life. We had a lot of time off there after playing, just to enjoy it.”

Life on the road can be grueling, she says. “I try to dance everyday. But after you’ve been on the road for two years, you just have to find one moment out of your day to do something healthy. … Some days I’m like ‘I miss my plants!’ Other days, I go to the Botanic Gardens in Hawaii.”

Talking to Valerie June for even a few minutes reveals a woman of intense spirituality who values deep introspection. She’s at home on stage, telling stories and singing in a ragged mezzo soprano with her signature trancelike cadence. Her towering dreadlocks and penchant for glamorous bearing make for a magnetic stage presence. But offstage, she’s an introvert who would probably rather be reading.

“You have to get in a rhythm to find out how to flow with the day, and how to preserve your energy,” she says. “My guys that I’m around all the time, they know that about me, and they’re really, really sweet and sensitive to my quiet zone. One of my girlfriends is like, ‘How do you survive out there on the road without any women around you?’ The guys just go and do their thing, going to bars, going shopping, meeting all their friends in different cities. I’m just in my little quiet space, like ‘Shhh’. And I’m all right.”

Her quiet time, where she strives to be present, is vital to her creative process. “Normally, I just write by hanging out and being around,” she told me shortly after the release of The Order of Time. “As I’m living my life, I hear voices. The voices come and they sing me the songs, and I sing you the songs. I sing what I hear.”

When I caught up with her more than a year later, she was working alone in her Brooklyn studio. “That’s the funny thing; I’m always behind on releasing songs, because I’m writing new things all the time. I have stacks of stuff, but I don’t put it out because it takes time to record it, package it, and promote it. Lately, so many poems have been coming to me. I wake up in the morning, and it’s just words, words, words. Beautiful words. I go through the day, riding the subway and writing it down. It’s like, when you see spring and the flowers are growing, that’s what it’s like with inspiration for words with me right now. That’s where I’m at. I’m constantly creating. But that doesn’t mean the world’s going to get it instantly!”

Valerie June is eager to return to Memphis for the Beale Street Music Festival. “My music was born in Memphis! It was always a dream for me to be able to play Beale Street Music Festival.”

She says her last two Memphis performances, one opening for Sharon Jones and the other at the sold-out Hi-Tone with Hope Claiborne and members of her musical family, have been highlights of her career. “They grounded us so good, with so much Memphis love,” she says.

Her rare visits to the Bluff City throw her out of her normal quiet road routine and into a whirlwind of activity. “Coffee here, lunch here, dinner there, I’ll pop in and have one glass of wine with so and so, then go across town to say hey to somebody. There’s so much love there. I don’t do friends any more. It’s fam, you know? People who I cleaned for or who came to Maggie’s Pharm or who worked in the coffee shops or came in to get coffee, all of these people come. It’s just really beautiful. One of the best emails I got in the last month is from a family I worked for over on Park Avenue. They live in Dubai now, and we haven’t talked for years. But they wanted to let me know that they still listened to my music, and thanked me for working for them. This is what I came from and who I am.”

Valerie June plays the Beale Street Music Festival’s River Stage on May 6th, at 3:50 p.m.

…

Tyler, the Creator

Tyler, the Creator

Provocateur and inspiration for a new generation of hip hop artists.

by Andria Lisle

“It is easier to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends,” Joan Didion wrote in 1967. So it is with Tyler, the Creator, who exploded on the national music scene as a member of the Los Angeles-based indie rap collective Odd Future in 2010.

When it comes to Tyler, running down a list of all the things that have brought him notoriety as an enfant terrible — internalized phobias that manifested as misogyny, racism, and homophobia — is easy. It’s infinitely harder to pinpoint exactly what makes him stand out — particularly amidst the marquee-worthy creatives he worked with in Odd Future, a roster including Earl Sweatshirt and Frank Ocean.

Even among those extraordinary artists, Tyler claims a celebrity status that’s all his own. Consider his activities of the past two weeks: On April 14th, he headlined Coachella, kicking off a 27-date summer festival run that includes stops at Beale Street Music Festival, the Montreux Jazz Festival, Afropunk Brooklyn, and Life is Beautiful. Four days later, he dropped a new song, “Rose Tinted Cheeks,” an unreleased demo from his dazzling 2017 album Flower Boy. The following week, he announced Mono, a collaboration between his clothing line GOLF le FLEUR and Converse.

Not bad for a brilliant, yet filter-less provocateur who was expected to flame out soon after staking his reputation on a controversial music video for the song “Yonkers,” which depicted him eating a cockroach, vomiting, and ultimately hanging himself.

When I poll the new wave of Memphis’ hip-hop community — younger artists who, like Tyler, are staking their careers on their own left-of-center artistic merits — it’s “Yonkers,” recorded and released in 2011, when Tyler was just 19 years old, that made them pay attention.

“I saw the ‘Yonkers’ video before I saw Tyler directly, and the world changed after that,” says producer and Unapologetic label owner IMAKEMADBEATS, who founded his label on an ethos that celebrates vulnerability and weirdness. “Tyler challenged every way you’re supposed to act to be a successful artist. His level of offensiveness is okay, because he’s sincere. We’re living in a different era where a young, skinny black kid can say crazy shit!”

“When I saw ‘Yonkers,’ I was like ‘Man, who is this dude saying all this wild stuff?’ He was true to himself. He wasn’t adhering to the capitalistic rules set forth by the music industry,” says digital artist and producer Kenneth Wayne Alexander II, an “anime surrealist” who, most recently, contributed to the musical score for Marco Pavé’s rap opera Welcome to Grc Lnd: 2030.

In 2011, Tyler provided an inordinately unique voice in an era of rap music that was dominated by mainstream acts like Eminem, Lil Wayne, and Wiz Khalifa. He came, seemingly, from nowhere, drastically shifting the popular music paradigm. Just as Nirvana had done exactly a decade earlier, Tyler instantly made most other artists sound outdated and irrelevant.

“It was representation during a time when all rappers were either drug dealers or drug addicts, or they were super fucking corny,” recalls contemporary visual artist Lawrence Matthews III, who performs and records under the name Don Lifted.

“Tyler is a regular dude who draws in notebooks and has crazy ideas and wants to do other stuff outside of rapping,” Matthews continues. “We both grew up skateboarding. We both grew up in a suburban sprawl. What comes with that is this outcast kind of thing — because you’re black, you can’t really deal with white people, but you can’t fit in with black people either, because you do white shit. I found a direct connection to him as a person, and the music followed. I didn’t always agree with his subject matter, but I understood it as this post-high school angst. It was very relatable. In the same way that I’m a child of Kanye West and Pharrell Williams and N.E.R.D. and skate culture, he’s a brother in that.”

A Weirdo From Memphis agrees. The Unapologetic rapper, who cites the dystopian art film Gummo as an influence with equal footing as, say, British MC and producer MF Doom, says, “Tyler, the Creator was extremely necessary in that environment. At the time, there was a general Lex Luger, 808 Mafia vibe going on, and Juicy J had just made his return. Then Tyler came along, and what he was doing felt so organic, so based on his individuality and personality that it just gave me the feeling that I could be myself, too. It was the first time I really felt that.”

Alexander, Matthews, AWFM, and IMAKEMADBEATS are all fans of Kurt Cobain — footage of the late Nirvana frontman even figures into Don Lifted’s performances — but in their world, Tyler easily overshadows the grunge pioneer. He is their Kurt Cobain. He’s someone who looks like them, someone with the same cultural touchpoints as theirs, someone who the outside world identifies as black, but, as Matthews said, someone who is also alienated because he doesn’t necessarily fit into his own community.

Like Cobain, Tyler’s relationship with fame, and his stability in general, has seemed precarious. But Tyler’s estrangement goes further; it’s become exceedingly clear, as he’s made his way through four studio albums, from 2011’s Goblin to the is-he-out-of-the-closet-or-isn’t-he cryptic beauty of Flower Boy, that Tyler has used his phobias to exorcise personal demons.

More than anything, Flower Boy forces listeners to reframe Tyler’s earlier releases. Rife with sexual clues that permeate a hothouse garden motif, the 46-minute album reveals a vulnerability that has unexpectedly bloomed amid all the aggressiveness. The end, it seems, is all about the journey — the arduous process is what makes Tyler fully complete. That vulnerability and process — and the unanswered questions both raise — have further endeared him to critics and audiences.

“It’s like seeing a child star growing up; they’re not on drugs, and now they’re doing really well for themselves,” says C.J. “C MaJor” Henry, a producer and engineer at Unapologetic. “Tyler’s influence right now is ridiculous. He’s legitimately being himself and it comes off as so cool that other people want it.”

Tyler, the Creator plays the Beale Street Music Festival’s FedEx Stage on May 4th, at 10:50 p.m.

Courtesy Beale Street Music Festival

Courtesy Beale Street Music Festival

Alex Greene

Alex Greene  Bianca Mayfield Burks

Bianca Mayfield Burks  Graham Burks

Graham Burks  Courtesy Beale Street Music Festival

Courtesy Beale Street Music Festival