When Drake’s dad walks into a bar, you notice.

He doesn’t walk so much as glide. It’s the first thing you see, that swagger. He wears immaculately white Nikes, white Adidas track pants with black-and-silver trim, a white shirt, two chains, a white do-rag, and a black knit cap. He stands about 5′ 10,” and his clothes hang off his lean frame, just loose enough to be cool but not baggy enough to look sloppy. His cologne is overwhelming, like a pine tree sprayed with Axe.

But it’s the mustache that steals the show. Thick and black, it swallows his upper lip and curls down as far as the bottom one. He’s had it since he was 15. Dennis Graham is the oldest man in the bar.

After grabbing a Labatt Blue, he walks back outside to a group of tables in front of the bar’s entrance. At the only occupied table, a girl examines him, her eyes locking on the newcomer.

“You’re somebody,” she says.

She knows she’s onto something but can’t quite figure out what. The Memphis sky is cool and gray, heavy with rain — and that lingering question. She pauses, looking him up and down.

“… Related to somebody?”

Graham — Drake’s dad — remains quiet and keeps walking toward the next table. But the girl doesn’t give up. She wants to know.

“Who are you?” she asks.

It’s a good question, one that begs asking and one that Graham surely sometimes asks himself. He wanted to be a famous musician. But if you believe the things that have been written about his relationship to his famous son and the things Drake has sometimes said and rapped about, Graham wasn’t always committed to being a good father.

Now, he is most recognized as a superstar’s dad. Beyond that, he is Dennis Graham, a veteran but mostly an unknown musician who’s never reached the big-time. He is also Drake’s dad, and his famous son has made it very big.

Is he somebody? Or is he simply related to somebody?

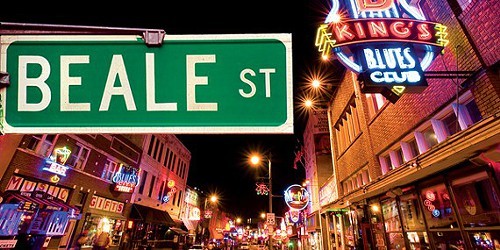

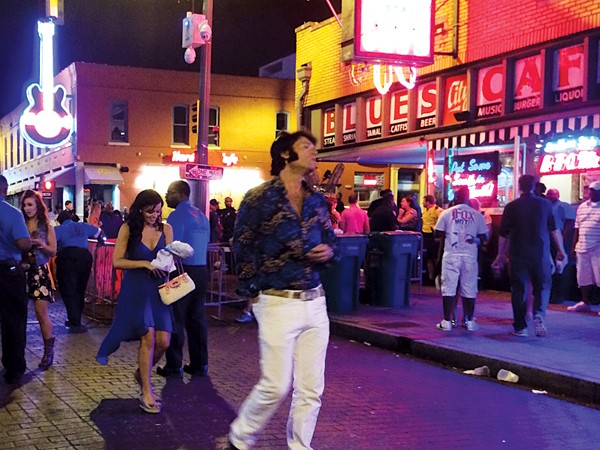

When he arrives at Blues City Cafe on Beale Street, a man exclaims, “There he is!” Hugs and dap follow. Inside, a waitress smiles at him. Toward the front of the bar, a large man — his size and demeanor give the impression that he only stands for special occasions — gets up from his table and walks over to shake Graham’s hand.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

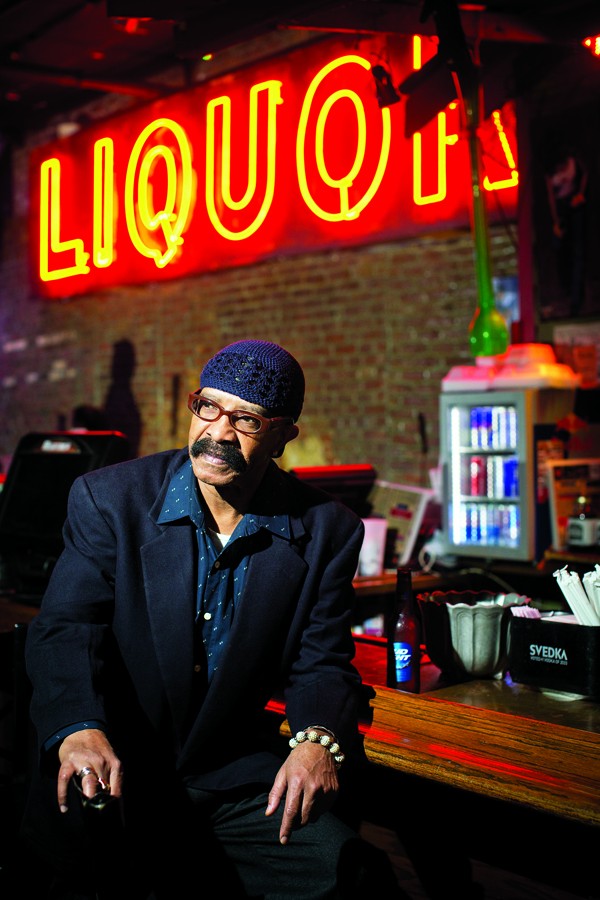

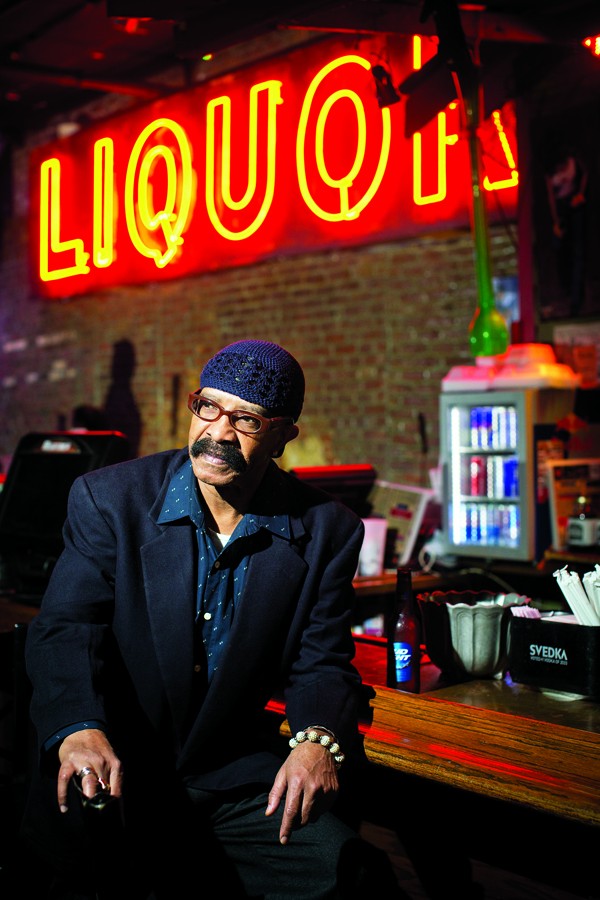

Dennis Graham hanging out at Blues City Cafe on Beale

The place is mostly empty. A poster advertising a Mike Tyson/Lennox Lewis bout hangs behind the front bar. Beyond it, 10 or 11 high tables soak in the neon-red tinge of a giant “LIQUOR” sign hanging near a well-lit stage. From the bloodshot shadows, eight or nine customers watch Earl the Pearl and his band perform their weekly Tuesday night set. A cool breeze carries deep bass lines and funky guitar riffs through the dark bar and into the night.

Graham takes a seat to the left of the stage. He knows these guys, and he knows they will ask him to get on stage and sing, to come out of the shadows and into the spotlight.

“I’m not gonna do it,” he says. Then, as if realizing he has closed a door he might want to keep open, he adds, “Depends what type of mood I’m in.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Graham has emerged from the shadows before — as a young boy playing music on the streets of Memphis. His cousin played the cardboard box. He played an overturned metal tub. Girls would dress up in their majorette uniforms and parade down the street with them, ribbons and everything.

One day they were playing on Union Avenue, downtown. Only a few blocks from Beale, Graham and his cousin sat on the street, beating on a cardboard box and a metal tub like they always did. But Graham stopped banging his drumstick — a broken mop handle — when he heard someone yell at him from above.

“Hey!” the voice beckoned. “Come here.”

It came from a man on a hotel balcony across the street. Graham walked over.

It was James Brown.

The famous soul singer called his drummer out to the balcony and made him give young Dennis his four-piece drum set. It was Graham’s first set of drums.

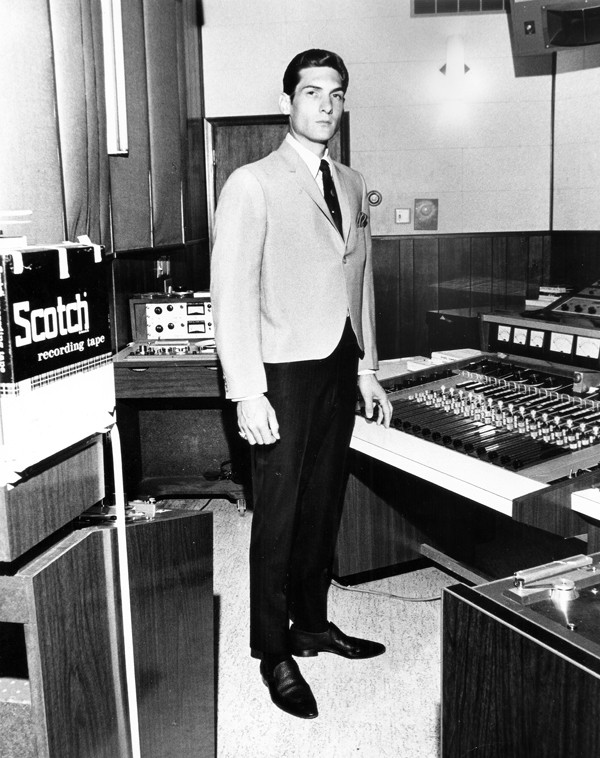

Graham went on to play drums professionally for Jerry Lee Lewis’ band. He also became a regular at Royal Studios, where Al Green recorded in the 1970s.

He played lots of gigs in Toronto, where he lived with Drake and Drake’s mother. But more time playing music meant less time being at home with his family.

“Yeah, that’s a hard one,” Graham says, before looking away. “I would never do it again.” He stares at the ground.

“That ruined part of his mother’s and my relationship. Yeah. I’m coming home after 2 a.m. every night and…” he hesitates, his distinctive swagger broken for the first time. “It just doesn’t work.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

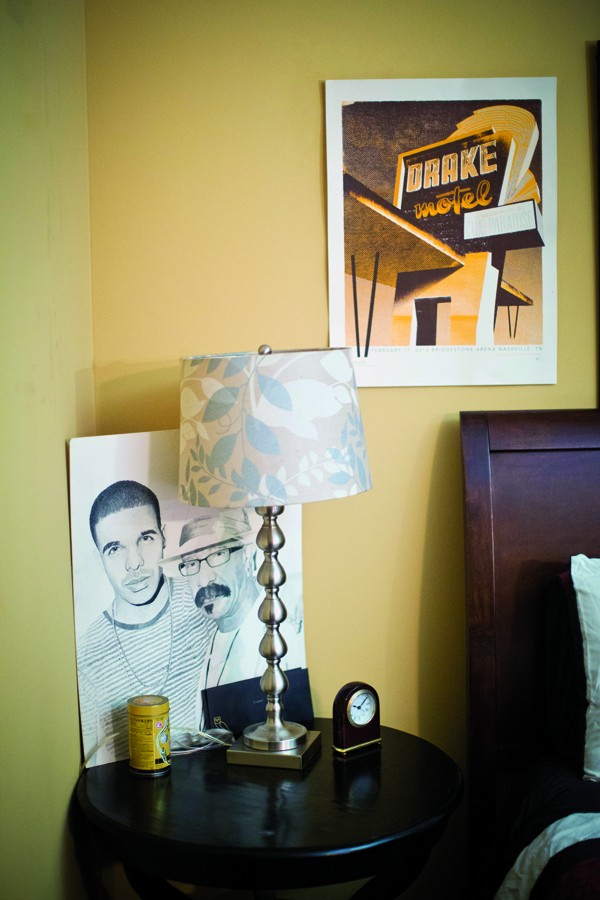

A little boy named Aubrey Drake would wait at home for Graham. Sometimes he would get to go onstage or into the studio with his dad. Other times he would be left alone, waiting, as he told GQ in an April 2012 interview: “Me and my dad are friends. We’re cool. I’ll never be disappointed again, because I don’t expect anything anymore from him. … I spent too many nights looking by the window, seeing if the car was going to pull up. And the car never came.”

Graham says some of his son’s lyrics and interviews paint an inaccurate picture of their relationship. But his son’s voice is big and gets heard; Graham’s voice does not. His reality never caught up with his dreams, and now he sits silently in a bar, not far from the streets where James Brown first found him.

“I mean, like, I played with a lot of people. I don’t name all the people I played with,” he’d says. He speaks confidently at first, then stumbles a bit through the next few sentences. “Like, I’ve worked — I mean, I’ve played with — God, some of everybody. You know, big stars.”

The more he talks, the less sure he sounds, like maybe speaking of it makes more tangible the vast distance between the world he used to inhabit and the one he occupies now, on this stool in this bar, sipping Bud Light and watching friends he knows from long ago perform without him. As promised, they try to goad him back onstage to sing “Stand By Me.” He declines, laughing and saying, “I ain’t sang in so long, I can’t remember the words.”

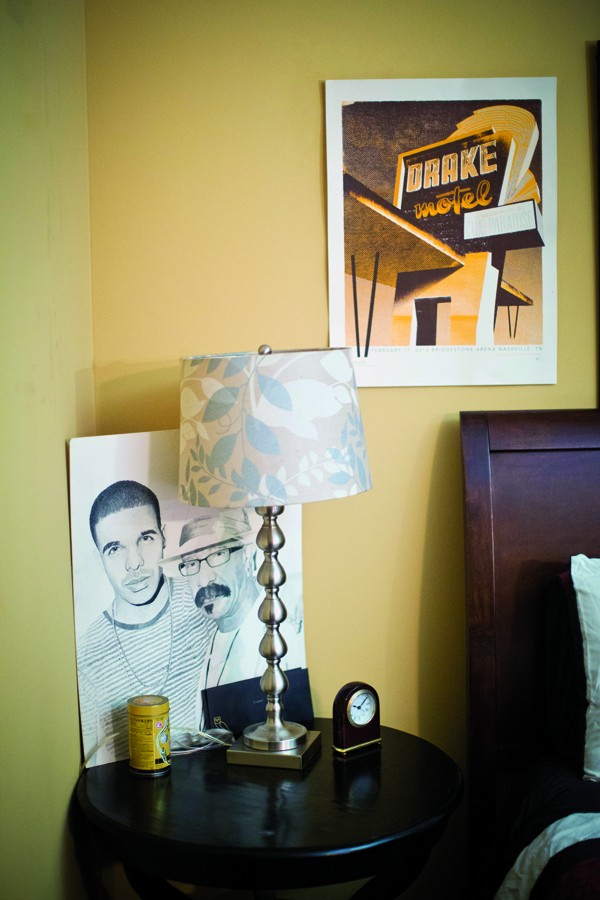

The bar stays pretty empty throughout the night and though locals say hi to Graham, he’s mostly left alone, a rare thing for a man who has become something of a folk hero on the street. Normally, there will be picture requests from adoring fans. Fans — Graham knows — of Drake’s dad, not of Graham. “The reason these people all want to take pictures with me is due to the fact that I’m Drake’s dad,” he admits, not without pride. “You know like, hey, I got a picture with Drake’s dad.”

Graham knows who he is, and he doesn’t mind.

“I want to be known as Drake’s dad,” he says. “That’s my son.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

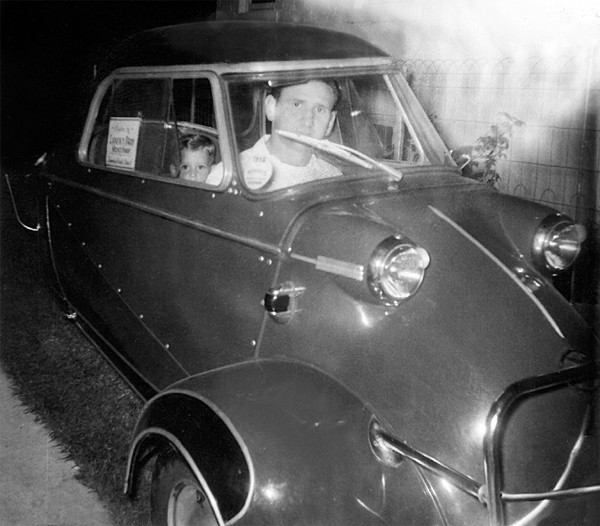

Graham sits in the driver’s seat of his 2002 Jaguar two-door, its V8 engine propelling him through the streets of his hometown. The windows are halfway down, and cold Memphis air flows in from the night. It’s dark and the glowing lights of the dash’s analog dials pool in the lenses of Graham’s red-framed glasses.

Every summer for 17 years, Drake sat next to him, making the 15-hour trip from Toronto to Memphis. Dad wanted to expose his son to the place and the music he called home. They would argue about what music to play. Graham wanted soul and blues — Johnny Taylor, the Spinners. Drake wanted rap. They would split it up, until Drake turned 17, and they started taking his car. Then, Drake got to listen to whatever he wanted. His car, his music. Then he left Memphis behind, going on to make the music the world came to know.

Those road trips are memories now. Graham reaches to turn on his sound system. His car, his music. He turns the dial, and the music gets loud.

It’s a new song Graham wants to release featuring Drake, his son.

Graham never became the musician he dreamed he would be, the musician his son eventually became. And he’s okay with that now. When Drake was a little boy, he bet $5 he’d do more television and more music than his daddy ever did. He was right, and when he came to Memphis for a show, a proud father gave his millionaire son $5.

“I don’t want to be that big star now,” Graham says. “I want him to stay the star.”

But now his son’s fame has turned him into something of a star, anyway. Graham stole the show in Drake’s music video for “Worst Behavior,” and toured with Drake and Lil Wayne last summer. When Drake asked his father to sing at his yet unplanned wedding, Graham said yes. He seems happy being dad, and Drake seems happy having one.

But he’s excited about this single, about how big a hit it might become and how many more people might get to know his name. There will be no more free interviews after this, he says.

Drake’s part hasn’t been recorded, so it’s just Graham on the track. The car fills with deep bass and cigarette smoke. Graham sits low, reclined in his beige seat, his right arm is bent at his side, holding what remains of an American Spirit cigarette. His left arm reaches straight forward, hand on the steering wheel. He grips it tightly, but his posture is relaxed. His foot taps to the beat. Though his mouth remains still under the thick, black mustache, his eyes smile.

At a red light at the corner of G.E. Patterson and Main, two ladies waiting outside a bar turn and look.

Five months from now, Drake still won’t have recorded his part, but Graham doesn’t know that now.

The light turns green, and Drake’s dad accelerates through the intersection and back toward Beale, through the streets and shadows where Graham used to play blues with a broken mop and a metal tub.

Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  The Bo-Keys

The Bo-Keys

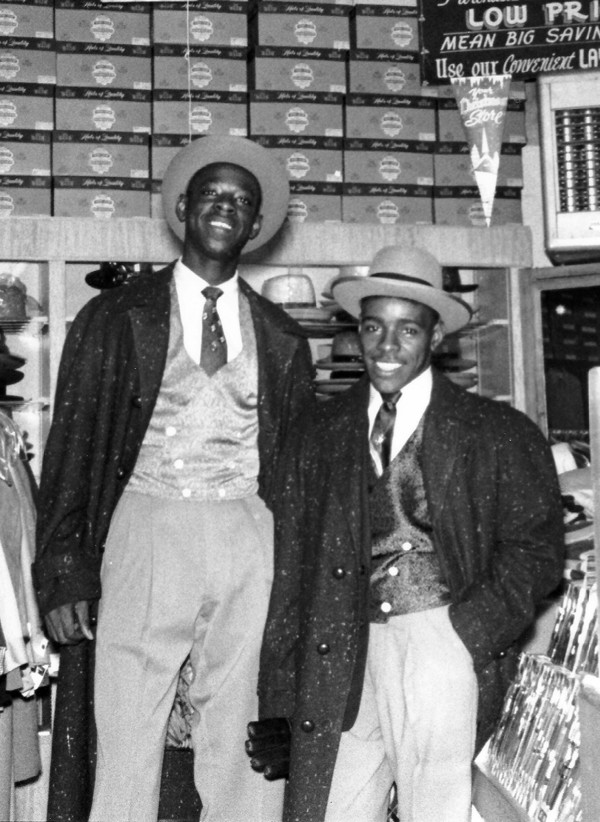

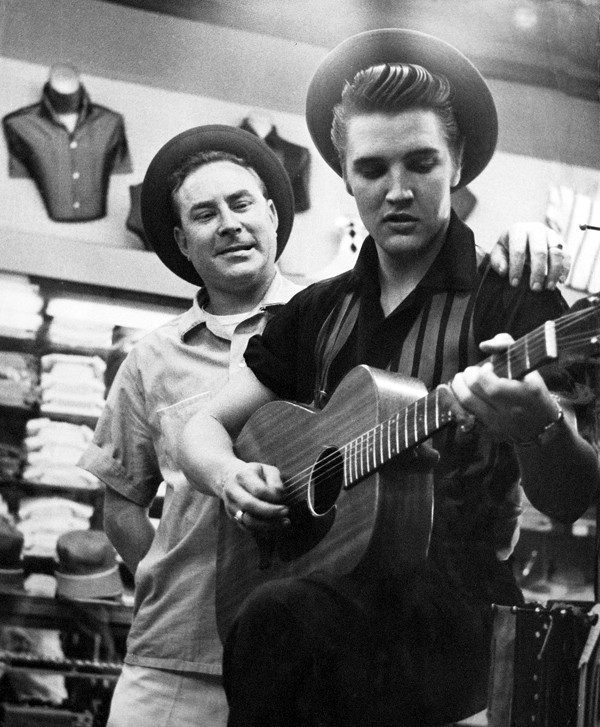

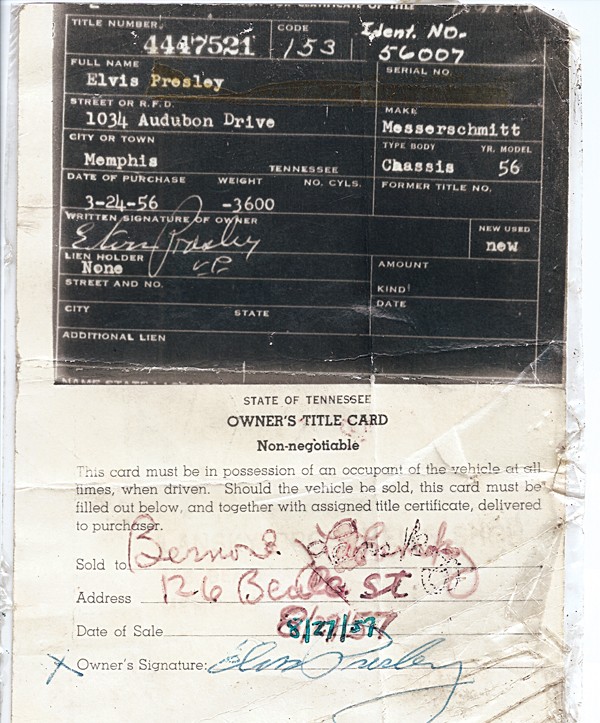

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives

Courtesy of Lansky’s Archives  Paul Morris

Paul Morris