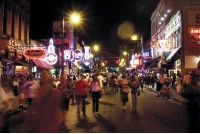

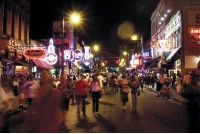

A generation has grown up since Beale Street went from nothing to the centerpiece of over $1 billion of downtown investment in music and entertainment.

For all the criticism it gets for security, music blend, and management, somebody is doing something right. Last weekend, while FedEx Forum was dark and Peabody Place and Gibson Guitar were barely stirring, Beale Street drew its usual sidewalk-to-sidewalk crowds of blacks, whites, Latinos, Europeans, the young, the old, the haves from the new Westin Hotel and the have-nots from the mean streets. They listened — as much as anyone actually listens — to music as different as the country twang of Double Deuce to James Govan’s blues at the Rum Boogie. They were watched by a surveillance system worthy of a casino and by groups of cops at every corner and barricade. They had fun, and they all got home safely.

But there is a considerable amount of nervousness about Beale Street’s future among its senior leadership. All those cops cost money, and security concerns never really go away. Locals are staying away. Memphis music to younger generations means not blues but rap, which is banned on outdoor speaker systems on Beale. The recession is cutting most everyone’s business, and per-capita spending has always been low because those crowds of kids can’t legally drink. The stakes are higher than ever because the bonds to build FedExForum depend on taxes generated by the surrounding attractions, and Beale Street is the healthiest.

One more thing: “Senior leadership” means just that. The developer/manager for 25 often stormy years, John Elkington, is 60 years old and ready to move on. The head of the Beale Street Merchants Association, Onzie Horne, rode as a child with his father and B.B. King in a touring bus in the 1950s and managed the career of soul legend Isaac Hayes.

Most of Beale’s old guard met for lunch last week to air some gripes along with a little dirty laundry to several members of the Memphis City Council. The mood was mixed. There was optimism about a unified entertainment district focused on the Beale Street “brand” reaching from AutoZone Park and the Peabody to FedExForum and the National Civil Rights Museum. But there were warnings, as well.

“Unfortunately, the way the climate is now, we are losing all our local support,” said Mike Glenn, manager of the New Daisy Theater.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Glenn, along with other veteran operators such as Preston Lamm (Rum Boogie Cafe), Bud Chittom (Blues City Cafe), and Tommy Peters (B.B. King’s), said the combination of a recession and security concerns have cut business 10 to 15 percent. Spending by international visitors, who enjoy a favorable currency exchange rate, is helping to offset waning local support.

Lamm said he and other owners want the city of Memphis and Elkington to work out their differences without a lawsuit so that attention can shift to improving security and growing the business.

Reports of a possible federal investigation of a privately owned parking garage south of Beale have produced bad publicity, as did the guilty plea on bribery charges of former Beale Street Merchants Association director Rickey Peete.

“We’re caught in the crossfire,” said Lamm, operator of the Rum Boogie, King’s Palace, and the Pig on Beale.

Peters, whose investment in B.B. King’s 17 years ago was a positive turning point for Beale Street, said business is “fragile” and is down significantly in the last four weeks.

Beale Street in 1981

The meeting was mainly a get-acquainted session for new council members and club operators. Lamm gave a brief history of the street’s 25 years. Horne gave credit to Elkington for “Herculean efforts” in seeing Beale Street through tough times in the early years. More recently, however, Elkington has been a focal point for criticisms on everything from minority representation to security and marketing. Horne said civil subpoenas have been issued to club owners, but complying with them would be “onerous.” He told council members that owners “have nothing to hide.”

Security has been a special concern since a private security guard was involved in a well-publicized physical confrontation with a patron last year. Merchants pay more than $300,000 a year for police overtime to officers who make $40 an hour.

“We’ve been able to keep all the tough trade out and keep our noses clean, but sometimes under the weight of the world you ask if it is worth it,” Chittom said.

Travis Cannon, owner of Wet Willie’s and one of the street’s younger operators, said he came to Beale Street in 2000 when business was booming. Lately, however, increasing numbers of panhandlers and homeless people have driven away business.

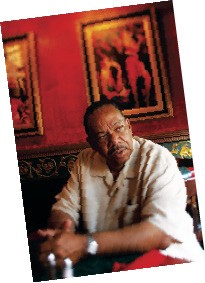

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

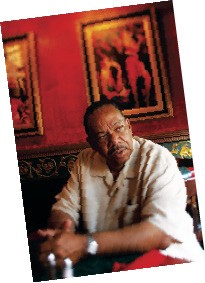

John Elkington of Performa

“We need to make people feel safe,” he said.

Horne, who replaced Peete and has been involved on and off with Beale Street since its opening in 1983, said Beale is the biggest tourist draw in the city, pulling in four million visitors and $40 million a year.

“I promise you, international tourists do not come to Memphis just to see the [Peabody] ducks,” he said.

Crowds of young people flock to the street around midnight on weekends and try to get inside the clubs or just wander around, several owners said. Clubs stay open until 5 a.m., and drinks can be sold and consumed on the street — in both cases, thanks to local legislative action.

“When they congregate in large numbers they intimidate our paying guests,” Horne said. “We have a security problem that needs to be addressed.”

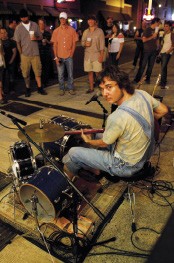

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

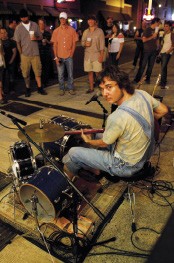

Street performer Richard Johnston

Lamm said Beale Street needs a guiding force. He noted, for example, that there are separate websites for the Memphis Convention & Visitors Bureau, Performa, the Beale Street Merchants Association, and the city of Memphis that feature Beale Street. Branson, Missouri, in contrast, has a single site where visitors and tour groups can plan their visit and buy tickets.

Horne also made a comparison to Branson, a white-bread shrine to former stars, fake stars, and fake-former stars in the Ozarks. The son of Onzie Horne Sr., a famous bandleader and arranger, Horne has no illusions about the differences between Branson and Memphis.

“We don’t have enough opportunities for people to spend money,” Horne says. “Any morning, you can see tour buses of Asians and Europeans pressing their faces against the window, and many of them will leave without spending any money or very little money. In Branson, these same tourists will take out their credit cards.”

The Beale Street of legend, he says, was a busy commercial street of doctors, photographers, coffee shops, churches, theaters, and merchants. Part of his job will be to restore some of that authenticity and expand the “footprint” of Beale Street, which has just two black-owned businesses and two female-owned businesses, while toning down its image as a place to buy a 32-ounce drink in a souvenir cup on Saturday night.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Onzie Horne of the Beale Street Merchants Association

Elkington’s weariness is evident when he discusses his 25-year-old work in progress. The number of locals who remember what Beale Street looked like before 1983 declines every year. He has pictures to refresh the memory, and he has written a book about Beale Street scheduled to come out in September.

His personal turning point came in October 2006, when he told his staff at Performa Entertainment that he was getting out. A few weeks later, however, Peete was indicted, and a few months after that a Beale Street patron was seriously injured by a private security guard, sparking a lawsuit and more bad publicity.

“We have a history of struggle on the street,” he says. “It took at least 10 years to get our momentum.”

Some of the people who come to Beale Street today are “much more aggressive and do not believe in respect for authority.” A few businesses he will not name have “catered to the lowest common denominator.”

He scoffs at rumors that he and/or the Lee’s Landing parking garage are under investigation, and he is proud that 70 percent of the investors in the garage and 30 percent of the investors in the Westin Hotel are minorities. He agrees he got a “one-sided contract” 25 years ago, but he says he’s willing to change it and has told Mayor Willie Herenton so “at least 20 times.”

The optimism that was once his calling card is tempered by hard experience. He says Peete, for all his faults, had the ability to make people work together. He has doubts about the bullish sales tax projections in the downtown entertainment district that backed the bonds to build FedExForum. On Beale Street, he flatly concedes, “we need new stuff” but it has to have the right stuff.

The modern version of Beale Street is 25 years old. With its 4 million visitors and revenues of $40 million a year, it’s obviously an irreplaceable asset for Memphis, but it faces a crossroads. Elkington puts it succinctly: “I’m 60 years old and I have a 6-year-old,” he says. “I’m interested in doing other things. We need to develop a new generation to take this forward.”

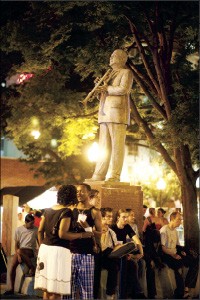

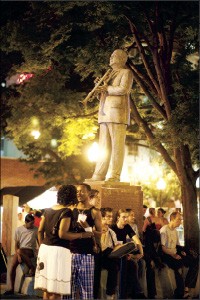

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

W.C. Handy statue

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens