Beyond police brutality and systemic racism, Black people, because of their hairstyles, music of choice, sexual orientation, and culture, often face discrimination, microaggressions, and prejudice in everyday life. Still, a tenacious pride abounds in the Black community. This is the story of five Memphians’ experiences as Black people in America. — Maya Smith

Black and Trans

Five years ago, Kayla Gore was robbed and stabbed in the shoulder with a butcher knife outside of her home in Memphis. With two bloody bath towels wrapped around her hands, which had been ripped open from attempting to grab the knife from her attacker, Gore waited for the police to show up. When they did, the first question the officers asked Gore is if the incident had been related to sex work.

Photographs by Maya Smith

Photographs by Maya Smith

Kayla Gore

“They acted as if I was a suspect instead of the victim,” she says. A week later, Gore found out that the District Attorney would not be pressing charges on the individual who attacked her.

“That was the end of that,” Gore says. “And I know that decision was solely based on me being Black and trans. If I were white and trans, or even just white, they would have prosecuted the case to the fullest extent of the law.”

Gore says this is not an isolated incident for Black trans women in America. “Even when we call the police for protection, the tables can easily turn from us being a victim to a suspect.”

That is just one example of the ways in which trans women of color are treated differently, especially in the South, Gore says. “Being a trans Black woman in the South feels like living in a desert where I don’t have access to a lot of things. It’s a resource desert, a safety desert, a housing desert. This is all because of how I show up with my transness and my Blackness.”

This is the “lived reality” for trans women in the South, Gore says. “I could literally walk out of my house and be killed because I’m Black and because I’m trans. People have their own personal biases about trans folks in the South, so it makes it even more dangerous for us.”

To make matters worse, Gore says there is no trans representation in elected or appointed officials on the local or state level, which makes her community “feel like we don’t have a space or a voice. When we elevate our voices, they’re erased.”

Feeling left out of spaces isn’t new for Gore, who recalls her first adverse experience because of her Blackness and queerness occuring when she was 8 years old. “I went to a very diverse church, but it was predominantly white. That’s when I noticed there was a difference in the way I was treated versus my white counterparts. I would get excluded from summer camps or sleepovers. It could have been because I’m Black or because I was queer, as I was definitely a very queer child.”

After that experience, Gore says her mother had “the talk” with her and she realized “I’m Black, therefore things will be different for me.” But different didn’t have a negative connotation for Gore: “I’ve always been proud of my Blackness because of how I was raised by my mother. I’ve always been super proud of how I show up in the world.” Much of that, she says, is the ability to connect to other people’s Blackness. “I’m fascinated with Black history. It fortified my love for my Blackness.”

It took a little longer for Gore to embrace her queerness though. She says for years she tried to be “stealthy, identifying as a Black gay man.”

But when she transitioned 10 years ago, Gore says she felt “like a whole new person. Pride became more than a day or a month, but a 365-day thing. I’m out and proud every day now. When I show up, people can’t help but see my transness, and I don’t think there’s a better way to show my pride than that.”

That pride led Gore to activism. For 10 years, she’s been advocating for better access and equality for trans women of color. Fully committed to the cause, she’s now the executive director of My Sister’s House, which provides emergency shelter and other resources for trans women of color in Memphis.

Gore’s hope is to make life better for “people like myself,” continuing the work of Black trans women who have come before her. “We have to pick up the baton and keep the marathon going until we reach liberation.”

Black and Preaching

Rev. Earle Fisher has always been going against the grain. When his first grade teacher in Michigan threatened to paddle all of the Black students, Fisher recalls protesting and walking out of the classroom. “I wasn’t going for it then, and I’m not going for it now. I’ve always been critical of racial injustice,” says Fisher, now the senior pastor at Abyssinian Missionary Baptist Church in Whitehaven.

Rev. Earle Fisher

As a Black pastor, Fisher says he’s in a “beautiful and complicated position. It’s beautiful because the Black faith has always been something that sustains Black people throughout history, even in Africa. In the United States, it was the impetus for resistance work that led to abolition, the Black Power movement, and the civil rights movement.”

Fisher says his role is also “complicated,” explaining that religion has historically “been co-opted and used as a tool of manipulation, especially in the white Evangelical strand of Christianity. It’s not always easy to embrace a Black pastor in America and especially in the South.”

This concern was at the forefront of Fisher’s mind one Sunday in 2015 when a white couple showed up to attend his predominantly Black church. Nervously reading over his notes, he questioned whether his prepared message would offend the couple and if he needed to change it for their sake.

“I immediately began to skim over my preaching manuscript in my mind, asking myself, ‘Am I going to say anything offensive to them?’ I know I can be a little edgy and unorthodox in my attempts to articulate the gospel on a grassroots and socially conscious level. I had to think about if I needed to dial it back. Do I need to assimilate to a more moderate conservative theology in my own church?”

Ultimately, Fisher says he stuck with his original manuscript and delivered a message with “unadulterated and unapologetic commitment to Black liberation theology, and they actually loved it. But the point is, how many times do you think a white pastor would question his sermon because of Black visitors?”

Fisher says when you grow up Black in America, “the air you breathe informs you of these social constructs that are a part of our reality. But it’s not a reality I was ever ashamed of.”

Fisher says he’s always been proud to be Black. He shows that on the pulpit, as well as on the streets through activism and grassroots involvement.

“I don’t have to apologize for my heritage or my ethnicity,” he says. “I don’t see it as a negative attribute. I thank God I’m Black. I don’t need to be ashamed about it. There are so many times where my Blackness is affirmed. How can you watch Serena Williams and not be Black and proud? How can you listen to Malcolm or Martin speak? Or how can I be in my house with my family playing spades, listening to the newest album, and not be proud? Just thinking about these moments gets me excited. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Black and in Business

As a college student in the Chicago area, Bartholomew Jones frequented many coffee shops. One thing he noticed about the shops was the lack of people who looked like him in the room.

Bartholomew Jones

“I never had a negative encounter,” he says, “but the whole experience was just white, from the people to the music playing over the speakers. So I just assumed coffee was a white people’s thing.”

That began Jones’ multi-year journey to learn about the history of coffee, which culminated last year when he started CxffeeBlack, a coffee company that seeks to “make coffee Black again.”

In his research, he learned that coffee originated in Ethiopia and was later brought to Europe.

“Black people in America don’t understand our cultural ties to coffee,” he says. “So the question was ‘What’s a way for us to provide more education on the history of coffee and also try to provide a way for more Black people to experience coffee?’ That was the inspiration for starting the company. I wanted Black people to feel like coffee was for them.”

Jones’ years in college opened his eyes to more than the lack of diversity in coffee shops. He also saw firsthand “the reality of how unequal society is.”

At Wheaton College, Jones says there were few other Black students on campus — so much so that he knew most by name. Growing up in Whitehaven, a majority-Black neighborhood, for most of his childhood, he says that was a culture shock.

“I noticed how much the white guys would drink and do drugs and there were never any police around. Meanwhile, I grew up in an overpoliced neighborhood. I got to see how the other side was living and what they could get away with.”

That wasn’t the first time Jones says he was made aware of the difference in the way he and his Black peers were treated. He remembers taking a ride with his mentor, who was white, during his senior year in high school. Jones asked if he could play one of his favorite CDs, a Christian hip-hop album by Lecrae.

“I put the CD in and he was immediately like ‘I have to show you something.’ He took me to the school basement where they keep old tracts and handed me a red pamphlet about types of demonic music, which of course included rap and hip-hop. But the reasoning was because they come from the ‘dark continent of Africa.’ I was speechless.”

Jones says he was aware of racism in a historical context, but not in the form of present-day prejudices. “It didn’t matter how many people were kind to me, they still hated my culture,” he says. “It didn’t matter how smart or nice I was, I was still Black in their eyes. Only if I conform and assimilate to their culture and listen to their type of music, am I then okay.”

Today, Jones fully embraces his Blackness, in part by “providing quality coffee for the ‘hood” and also by protecting and uplifting other Black people.

Jones says the most important part of that role is being the father of two young boys. He and his wife want to ensure their sons are prepared for what they might face as Black men in America, he says.

“We want to give them a new narrative, though. We don’t want our boys to think they are destined to be killed by police officers. We have to give them the tools to protect themselves and overcome obstacles they will encounter as Black men. Most importantly, we teach our kids that they are Black and they should be proud of it.”

Black and Non-Binary

When Mia Saine was in preschool, they were bullied because their skin was darker than their classmates’ and their hair was a different texture.

Mia Saine

“This was the first time I remember any form of discrimination,” they say. “I mean, imagine being a 4-year-old and someone pointing out your features that make you different or implying those features make you not desirable to befriend. It was hard.”

Later, Saine remembers seeing Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” on TV for the first time and recalls that being the earliest moment they were proud of their Blackness.

“I got to see Michael Jackson playing this role as a zombie. He was on TV. It was just so magical. My parents introduced me to a lot of Black music, and I started to feel a sense of pride for our culture.”

Saine, born and raised in Arlington, is an illustrator and graphic designer in Memphis. They are also Black and non-binary, which they say “is a protest itself. Every day I’m going against the so-called normal lifestyle and American Dream. But that just doesn’t represent who I am as a person.”

As a high school student in Arlington and then a college student at Memphis College of Arts, Saine says they had to learn how to navigate predominantly white spaces, but there were times “when I was uncomfortable and just couldn’t relate because I didn’t have certain privileges and opportunities.”

Now, a full-time professional artist, Saine says that discomfort continues. Often in meetings, “I’m the token Black person. There have been times where I’ve been like ‘Oh yeah, this conversation is happening because I’m Black.’ It’s infuriating. However, having been on both sides of the coin, I know how to adapt and code switch.”

As an artist of color, Saine says “every time I present something, it’s over 100 percent, to surpass the expectations for that of a Black person. I feel responsible to represent a whole group of people. Being a non-binary Black artist is an empowering thing for me.”

However, Saine says they “feel obligated to go above and beyond to prove myself worthy in a way I shouldn’t have to. I have to overcompensate so often. But at the same time, I’m the type of person who won’t stand for any kind of discrimination. I don’t want to be seen as the angry Black woman, so I have to figure out how to be diplomatic but still stern.”

Despite the challenges over the years, Saine says they’ve come to love their queerness and Blackness, realizing “I should just love myself for me and advocate for all of my qualities instead of trying to seek approval and forgiveness. I can’t wait around for people to understand me. I have to live my life.”

Saine says they’ve felt more hopeful about the future for Black Americans in the past few weeks, seeing more people “accept the reality of people who are like me, my friends, family, and loved ones. Because we matter so much. We just want to be valued. That’s all.”

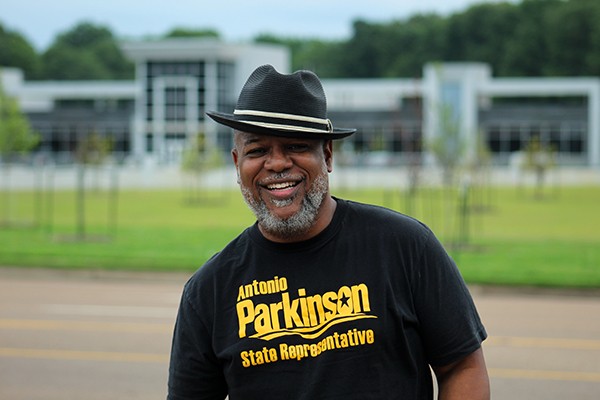

Black and Elected

Antonio Parkinson’s dreadlocks were below his ears when he had to cut them in order to keep his job at the Shelby County Fire Department.

Antonio Parkinson

“I started to grow dreadlocks,” he says. “There was no policy in place at the time, but they wrote me up, and when I wouldn’t sign the write-up, they were ready to suspend me. They told me I had to cut them or I’d be fired. So I did, and it made me feel terrible. I felt singled out. They didn’t understand my culture and weren’t trying to at the time.”

Parkinson says hair discrimination is just a drop in the bucket of what he experienced during his 25 years working for the fire department. From racial slurs to attempts to thwart the promotion of him and other Black firefighters, Parkinson says the culture was one of “suppression for people that look like me.”

He thought about walking away several times “when it got ugly, but I’m a fighter so I stayed. I simply looked at it as ‘Why not me?’ Why should your child and family have opportunities and not mine? Why can’t I do something that will create generational wealth for my family?”

Now, in his ninth year as a Tennessee state representative, Parkinson says his experiences over the years have only added fuel to the fire, motivating him to create legislation, such as healthy workplace laws to prevent discrimination on jobs and the Tennessee CROWN Act, which would make it illegal to discriminate against natural hair in the workplace.

“I just wanted to get some stuff done,” he says of his decision to run for office in 2011. “I wanted to level the playing field for everyone.” But discrimination and racism is still a reality for Parkinson.

“The Tennessee legislature is rampant with racism,” he says. “There’s overt racism. There’s covert racism. It’s in the racist jokes and slurs to the policies. And if you say something about their racism or racist statues, then they want to kill all of your bills.”

For example, Parkinson says no people of color had any input that made it into the state’s budget this year. “Not one single person of color had something in the budget. What does that say? The budget is a moral document that determined the priorities for the state.”

“Sometimes it gets discouraging,” he says of his role as a legislator in the majority-white General Assembly. “Sometimes they’re practicing discrimination and don’t even realize what they’re doing is racism. They say things that are not necessarily from a place of malice, but a place of ignorance. So part of my job is educating them.”

Despite the discrimination over the years, Parkinson says he has always been proud of being Black.

“I knew I was Black early on. My mother wouldn’t not let me know. She taught me who I was and how proud I should be. I loved and still love being Black. There’s nothing like the culture and everything that comes with it.”

Because of that, Parkinson says he is an “unapologetic, uncut version of myself. We shouldn’t have to compromise who we are, at all. I don’t care if you have gold teeth or weave down your back. We don’t have to compromise our culture. This culture is dynamic with everything from natural hair to 26-inch rims to bass in the music. We should not be ashamed or dumb down who we are for someone else’s comfort.”

Mike Blake | Reuters

Mike Blake | Reuters