The Double-Headed Eagle.

“The cause of human progress is our cause, the enfranchisement of human thought our supreme wish, the freedom of human conscience our mission, and the guarantee of equal rights to all peoples everywhere, the end of our contention.” So begins the Scottish Rite creed, a set of ideas evidenced in the Masonic order’s welcoming of ambitious works by nearly 50 local, national, and international artists into their grand temple at 825 Union Avenue, a building frozen in time, and already laden with symbols, murals, and decorative detail.

Curated by Jason Miller, “Circuitous Succession Epilogue” brings together a variety of artists working in mediums ranging from wood and steel to fragile ceramics and plastic Walmart grocery sacks. The artwork can also be heady, exploring a range of topics from economic disparity to corporate dominance to female exclusion. It may also be witty, as is the case with stairwell installations by sculptor Greely Myatt, and a tricky piece by multimedia artist Jay Etkin that has been used by Miller to create a kind of hide-and-seek game with visitors.

Inside the Scottish Rite Temple: Circuitous Succession

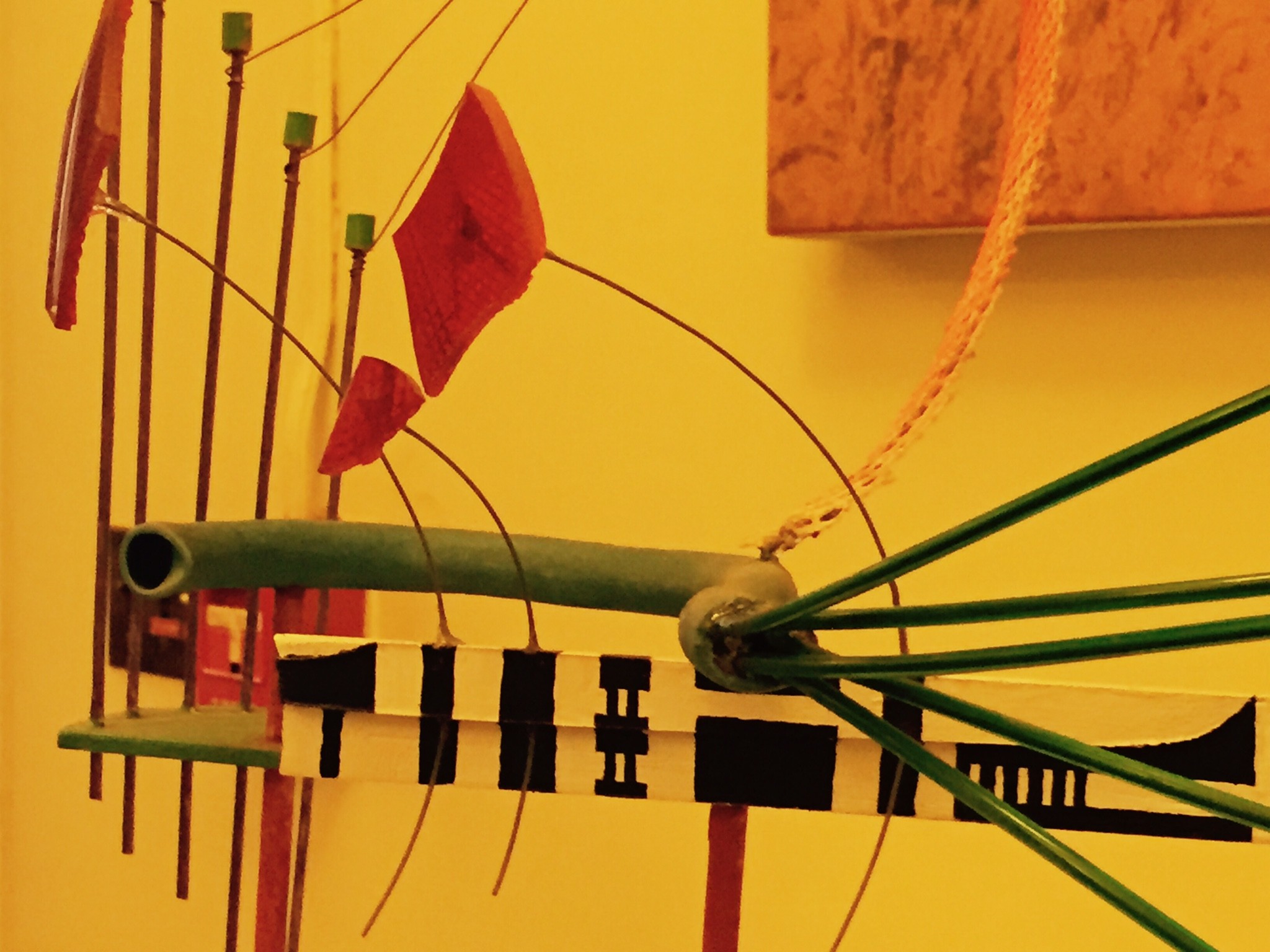

Sculpture by Roy Tamboli

Sculpture by Roy Tamboli

The Scottish Rite building is three stories with a dining room and a grand theater that was expanded and refurbished when it was used to film performance scenes for the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line. It is already outfitted with ornamental work, masonic symbols, and portraits of past members.

Inside the Scottish Rite Temple: Circuitous Succession (2)

Secrets inside

Miller, who curated his first exhibit in the grand, non-traditional space a year ago, is also a conceptual artist who believes that an artwork is completed by its surroundings. The Scottish Rite gives him a lot to work with.

The rose cross.

Miller can’t stop talking about the depth of talent in his show and seems especially excited about four pieces created by Shara Rowley Plough. “It’s called Maids Work,” he says of the collection. “She wove maids’ garments out of Walmart shopping bags. They are so detailed; it must have taken her a year.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Jason Miller, behind the board. Backstage at the Scottish Rite Temple

Going up?

Door detail

A better look at the board.

Sculpture by Anna Maranise

Anna Maranise’s sculpture, installed in front of an allegorical Scottish Rite mural, provides one of the exhibitions best interactions between art and environment. Miller describes it as being like a “Cronenberg film.”

The old masters. Masons, that is.

Sculpture by Jay Etkin

No smoking signs are everywhere.

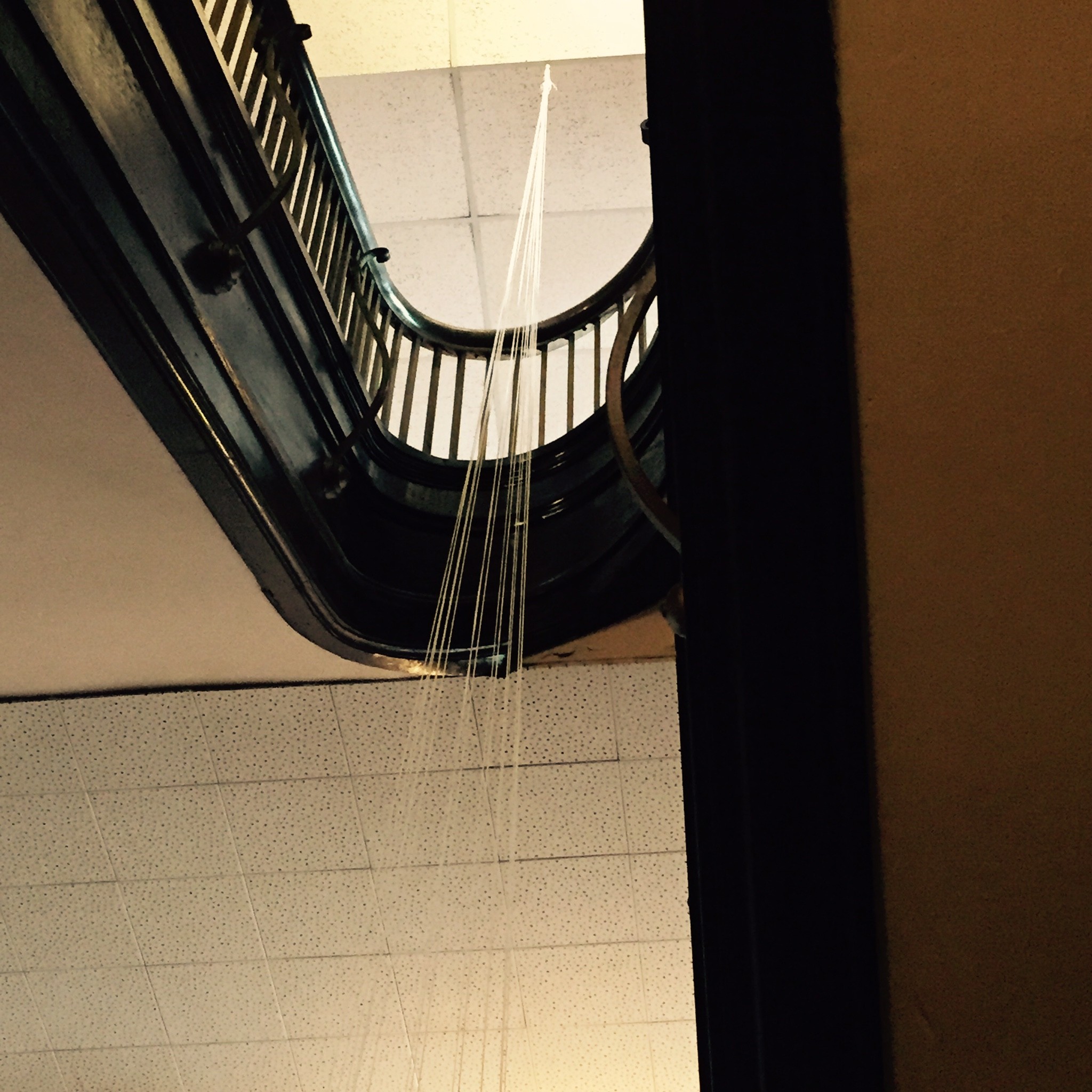

Installation by Greely Myatt.

More places to store your hat and coat.

It’s impossible to really capture how the above piece resonates in its space, below a Masonic ceiling mural. You really do have to see it to get it.

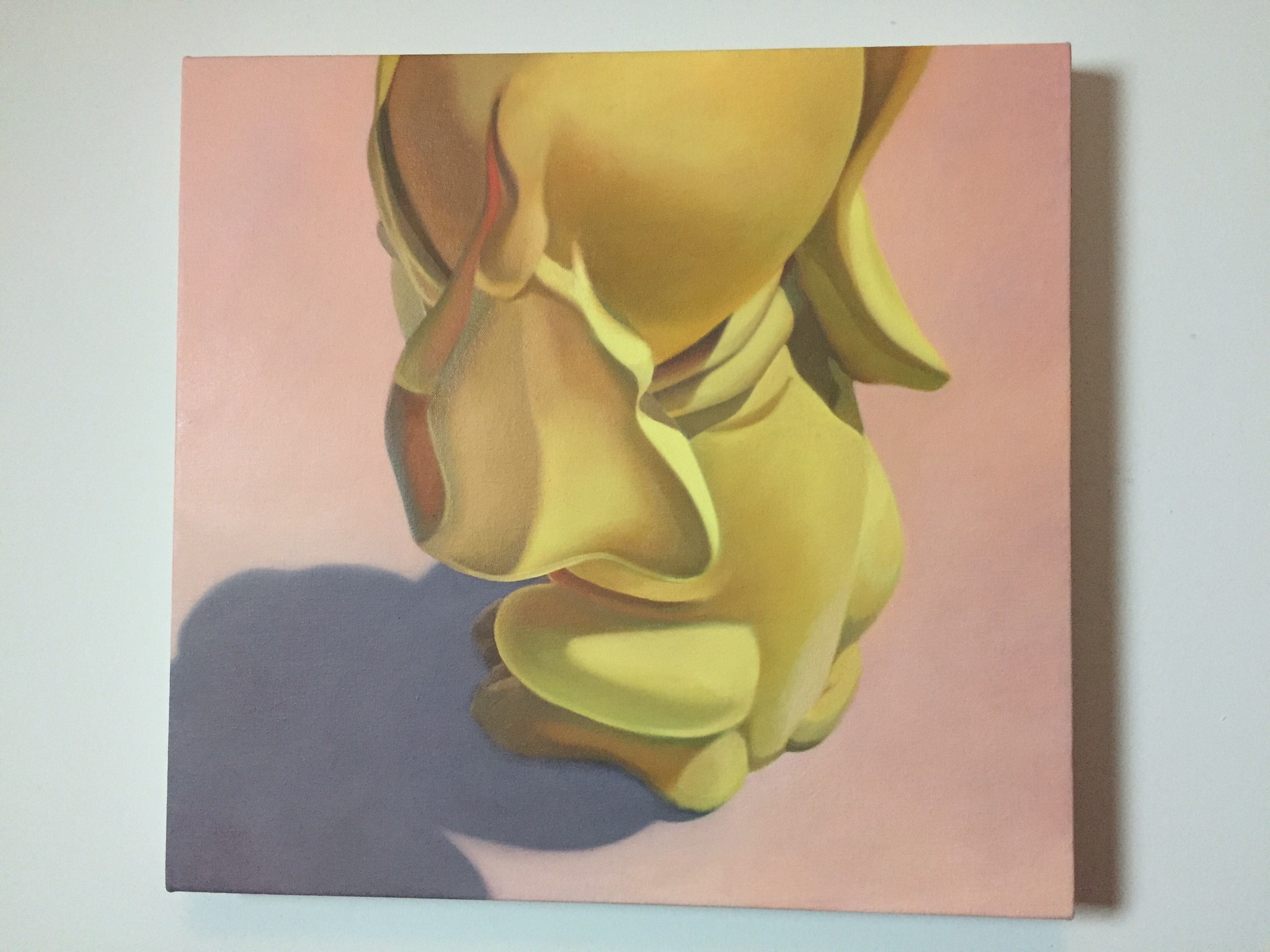

A painting by Beth Edwards

Chair.

At times it’s impossible to tell where the exhibit ends and the Temple begins. Everywhere you turn there’s a William Eggleston photograph just waiting to be taken.

It’s an impressive organ. No other way to put it.

Theater detail.

More backstage stuff.

Costumes abound.

More costumes.

More places to store your hat and coat.

Buckets and a radiator.

Stairs

Art

Fire escape

More chairs

Rope hanging in a window

All that and a place to store your cloak. Members only.

Miller can’t stop talking about the depth of talent in his show and seems especially excited about four pieces created by Shara Rowley Plough not pictured in this post. “It’s called Maids Work,” he says of the collection. “She wove maids’ garments out of Walmart shopping bags. They are so detailed; it must have taken her a year.”

Circuitous Succession is an ambitious instillation in an impressive space that’s majestic in some corners, and bit frayed at the elbows. The art alone is compelling enough. In the temple, it’s downright irresistible.