The blues may be a foundational element for most of American music, but these days the genre is pretty self-contained — widely restricted to a network of specialty clubs and festivals catering to a loyal base of fans. The Blues Music Awards — the annual “blues Grammys” sponsored by the Memphis-based Blues Foundation since 1980 — is of and for this base of committed fans. The event moves to the Mississippi Delta for the first time this year, landing at the Grand Casino Event Center in Tunica on Thursday, May 8th.

But this year the awards showcase a trio of artists — chitlin-circuit kingpin Bobby Rush, deep-soul reclamation project Bettye Lavette, and eclectic roots-music bandleader Watermelon Slim — who represent a broader vision of blues culture. Perhaps it’s a sign of health that the three highest-profile nominees this year are all artists with cachet both within and outside the parameters of the contemporary blues scene.

Together, Slim, Lavette, and Rush have garnered 13 nominations across 10 of the 25 award categories. All three are among the five nominees for the night’s biggest award, the B.B. King Entertainer of the Year, while Slim and Lavette are both up for the other big prize, Album of the Year, for their 2007 discs The Wheel Man and The Scene of the Crime. Rush, meanwhile, is the first person in the ceremony’s history to be nominated for Artist of the Year in both the Acoustic and Soul Blues categories.

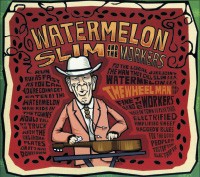

Watermelon Slim & the Workers lead the nominations for the second year in a row, with six. In addition to the aforementioned album and entertainer awards, Slim and his band are up for Band of the Year, Contemporary Blues Album of the Year, Contemporary Blues Male Artist of the Year, and Song of the Year (for “The Wheel Man”).

Only three years after being a Best New Artist nominee at the BMAs, Slim is racking up the kind of notice previously reserved for the likes of Robert Cray and B.B. King, and the fascinating, satisfying The Wheel Man testifies that the attention might be deserved.

Like Jimmie Rodgers, another working-class hero, Slim is a blues-loving white guy who blends country into his sound. The generally stomping electric blues on The Wheel Man is almost totally devoid of blues-bar-band clichés, with echoes of field hollers and jump blues thrown into the mix. And Slim proves to be a sharp songwriter too: “Drinking & Driving” (“You better pull over baby instead of drinking and driving me away”) is one of those songs you can’t believe hasn’t already been written.

Content-wise, the album mirrors the diversity of experience of the man himself. “Newspaper Reporter,” about one of Slim’s past career paths, acknowledges his white-collar credentials, while the title track and “Sawmill Holler” speak to the blue-collar experience that has seemingly shaped him more.

In addition to the two big awards, Lavette is also nominated for Contemporary Blues Female Artist of the Year. Never exactly a straight-blues artist, Lavette is among the many survivors of the ’60s soul scene that never quite hit. Detroit-raised, she recorded for regional indie labels and for Atlantic, cutting sides in soul hotspots Memphis and Muscle Shoals, but never had that big breakthrough. By the ’80s and ’90s, she was a live performer who rarely recorded.

Then earlier this decade, Lavette embarked on the comeback that most of her era and predicament can only dream of, inspiring an overseas reissue boom at the outset of the decade and then re-emerging fully with 2003’s A Woman Like Me, a reintroduction produced and guided by former Robert Cray collaborator Dennis Walker.

From there, she moved on to Anti-, an indie label that’s lately specialized in rootsy prestige artists, first with 2005’s I’ve Got My Own Hell To Raise and then with last year’s The Scene of the Crime, an album recorded at her old Muscle Shoals stomping grounds with the Drive-By Truckers on back-up.

Lavette shows off her chops as an interpretive singer by claiming Willie Nelson’s “Somebody Pick Up My Pieces” and Elton John’s “Talking Old Soldiers” as her own. But the real showcase is the album’s only original song, written with trucker Patterson Hood, “Before the Money Came (The Battle of Bettye Lavette)” — an autobiographical statement of purpose that acknowledges a whole new audience (“I was singing R&B back in ’62/Before you were born and your momma too”).

Rush, by contrast, is not a comeback story. He’s an institution. Unlike Lavette or Slim, he doesn’t so much straddle the blues scene and more general music fans. Instead, he represents a constituency that you might think would be absolutely central to the “blues” audience but really isn’t: working-class African-American adults.

In addition to Entertainer of the Year, Acoustic Artist of the Year, and Soul Blues Male Artist of the Year, Rush is nominated for Acoustic Album of the Year for his 2006 country blues disc Raw.

Raw comes across as somewhat of a bid for respect, the kind that — in the words of colleague Chris Davis — being a “big-panty provocateur” doesn’t always provide. It’s mostly a solo, acoustic affair, stripping away the ostensibly cheesy soul flourishes that are too fun and, in its own world, too contemporary to be deemed authentic and respectable by roots puritans. Not that Rush — a sublime entertainer in his more typical element — gets too staid here. The opening “Boney Maroney” has some of the lascivious, mischievous qualities we expect, while the closing “I Got 3 Problems” refers to the complicated trinity of “my girlfriend, my woman, and my wife.”

If Rush, Lavette, and Slim represent the possibilities of the blues today — as traditional music alive in the modern world — then the blues is doing alright. All three are slated to attend the ceremony.