The concert film is always a tightrope walk. For every thrilling crossing over like Stop Making Sense, there’s a ponderous failure like The Song Remains the Same.

April brings two concert films that are similar on the surface. Both of them feature black women whose gifts far exceeded their contemporaries, man or woman; black, white, or otherwise. Both are stitched together from two nights of performance, which enlist non-professional musicians playing unfamiliar styles. And in both cases, the artists are at a crossroads in their lives, and are both looking back and choosing how to reinvent themselves for the future. But the two films could not be more different in mood or execution.

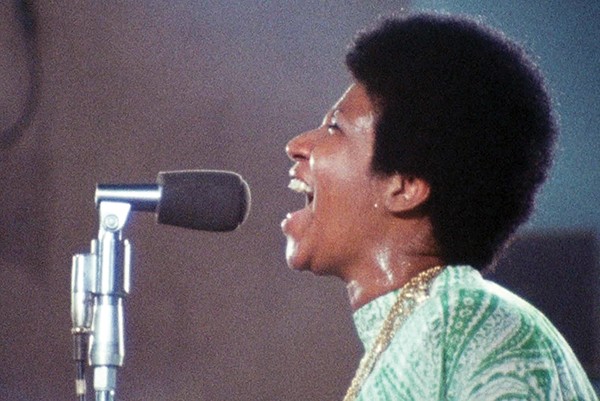

Aretha Franklin, who was born in Memphis, grew up in the church. She learned her peerless chops performing as a teenager with her travelling preacher father, C.L. Franklin. In 1972, she was four years into an unprecedented eight-year run of winning Best Female R&B Performance Grammys, and was regularly churning out top 10 hits like “Respect” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.” Instead of going back to the studio for another conventional soul record, the Queen of Soul holed up in the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church with Rev. James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir, led by a man with the unlikely name of Alexander Hamilton. Recorded before a live audience, Amazing Grace, is the best selling live gospel record of all time.

Amazing Grace LLC

Amazing Grace LLC

Amazing Grace showcases Aretha Franklin’s amazing voice.

The sessions were filmed by director Sydney Pollack, and Warner Bros. intended to make a TV special out of the footage. But when editors tried to synch the recorded sound with the mountain of 16mm film canisters, the project ended up scrapped, and the reels moldered in the Warner vaults for decades. But thanks to software like Plural Eyes, synching wild sound has become much easier in the digital era. With the help of Spike Lee, director Alan Elliott finally cut together a version of Amazing Grace, only to have Franklin sue to keep the footage hidden. After her death, Franklin’s estate got a look at the film and agreed to release it in theaters on Easter weekend.

It’s easy to see why Franklin would have bad memories of the Amazing Grace sessions. The meta story the footage tells is of a film crew completely unprepared for the conditions they would face, and a director desperately trying to get a handle on things while music history unfolds around him. But what made the footage unusable for TV in 1972 makes it gold now. Franklin’s performance is celestial, but the grainy film and haphazard framing serve to ground her as a human being. We’re a fly on the wall as magic unspools in front of us, and it is absolutely mesmerizing.

In 2018, Beyoncé Knowles became the first black woman to headline the Coachella music festival. She had been scheduled to perform in 2017, but she had to cancel because of a high-risk pregnancy that ended with the successful birth of twins. In her first show after almost dying, the most consistent hitmaker of the 21st century and feminist icon to millions pulled out all the stops. She could have done a victory lap of hits with backing tracks, brought out Destiny’s Child for an encore, and everyone would have gone home happy. Instead, she assembled not just a big band, but an actual, literal marching band.

Homecoming shows Beyoncé headlining Coachella music festival.

Beyoncé may not be the first to reinterpret her music like this — David Byrne and St. Vincent have done it, too — but arranging “Crazy in Love” and “Formation” for drum line, tuba, and brass adds depth and complexity to the insidiously danceable beats. The set, which created a pyramid out of metal football bleachers, turns out to be key to the ingenious staging, which smoothly shuffled more than 200 dancers and musicians. The face she shows the Coachella crowd is perfection, but Beyoncé, who directed the film as well as all other aspects of the show, takes care to highlight the months of planning and rehearsals that led up to the big moments.

As a musical spectacle, Homecoming has few equals. As a film, it could have been a lot tighter. As a musician, watching the prep work that goes into a show like this is fascinating and inspiring, but those segments seemed timed to kill the live show’s momentum. Since Homecoming is on Netflix, you can fast forward past them to get to the good stuff. Nobody’s perfect. Not even Beyoncé. But she’s damn close.