Need to get from East Memphis to downtown by bike?

Hit the Shelby Farms Greenline. North on Tillman to the Hampline. Through Overton Park. North on McLean to the V&E Greenline. Then, west on North Parkway all the way to Mud Island.

Sound confusing? Not to hardcore Memphis cyclists. They’ve navigated the city’s system of bike trails and lanes as its grown over the past few years. But a new tool will unlock the cycling scene here for anyone looking to get on two wheels.

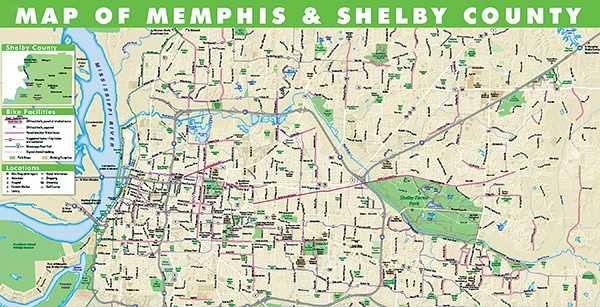

Convention and Visitors Bureau map shows all the bike lanes and trails across the city

The Memphis Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) has published the Memphis and Shelby County Bike Map. It’s the city’s first-ever printed map of the city’s bike trails, lanes, shared roadways, bike shops, and suggested bike routes.

“We made the map to support the current infrastructure, and we’re anticipating the worldwide attention we’re going to get when the Harahan Bridge project is ready for cyclists to cross the river,” said Regena Bearden, the CVB’s vice president of marketing and public relations.

Big River Crossing, a new walking and biking path across the Mississippi River via the Harahan Bridge, is slated to open next summer. Local officials believe it will make Memphis a cycling destination, especially with its promised connectivity to a system of levee trails stretching to New Orleans.

Just a few years ago, becoming a cycling destination seemed unlikely for Memphis, especially as Bicycling magazine called it one of the worst cities for biking in 2008. But the city has since done a U-turn. Memphis has added 108 miles of bike lanes since 2010 for a total of 198 total miles of bike lanes, shared paths, shared lanes, and more. This earned the city Bicycling magazine’s “Most Improved City Award” in 2012.

But some things about the Memphis system become clear when you look at the new bike map. Memphis bike lanes aren’t very well connected. Many begin and end at seemingly random places. They don’t seem designed to deliver bike riders to anywhere specific.

That’s because bike lanes are only created when a street is paved, said Kyle Wagenschutz, the city’s bicycle and pedestrian coordinator. But better connectivity is on the way, he said.

Thanks to federal transportation grants (with a 20 percent local match), more than 130 new miles of bike facilities are set to be created here by 2016, nearly doubling the amount of current bike lanes.

“The grant-funded projects were specifically chosen as a way to bridge the gap for a lot of those bike lanes,” Wagenschutz said.

The emphasis on bicycles in Memphis comes as the city embraces its outdoorsy side.

“I think there’s a transformation going on here when you look at bike lanes, hiking, the Harahan Bridge, Greenline, Shelby Farms, and Bass Pro, which is going to attract the outdoorsman, the hunter, the fisher, and the outdoor enthusiast,” said CVB President Kevin Kane. “We’re adding another dimension of the visitors we can attract here.”

The new bike map can be picked up at the CVB office and bike stores across Memphis. Find it online at memphistravel.com.

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips