In 2010, Memphis was the 18th-largest city in the country but had only 1.5 miles of bike lanes. Now, just seven years later, the city is on track to have 400 miles of bike-friendly thoroughfares.

Memphis has the chance to be a great biking city. That’s what the city’s Bikeway and Pedestrian Manager, Nicholas Oyler will tell you. That’s in part, he says, because of the city’s flat topography, its fairly mild climate — aside from July and August — and traditional street grids throughout the city that work well for biking.

Apart from recreation and exercise, Oyler says, biking can play an important role in the city’s transportation network. “In a city where a quarter of the people are living below the poverty line and might not have access to a car, biking isn’t just a fad or exercise, it’s how they get around, how they do their daily life.”

There are lots of big plans and innovative projects underway to help bicycling to become a part of “doing daily life” for many more Memphians — and in areas where safe bike facilities could really make a difference.

Sylvia Crum

Sylvia Crum

Teen ambassadors in the Big Jump Program help lead the charge to make biking in Memphis safer and more convenient

The Big Jump

The Big Jump: Making Bicycles a Part of Daily Life in Memphis

“That’s not right.”

That’s what 11-year-old Joshua told me as he reached over from his bike and adjusted my helmet straps for me. “You have to make sure the buckles are right under your ears, like this,” he said, pointing to his own helmet.

He learned that — among other biking tips — as one of the 11 young “ambassadors” of the Big Jump program, a three-year initiative aiming to make biking in South Memphis safer and more convenient.

Memphis is one of 10 cities chosen from nearly 100 applicants nationwide for the Big Jump program, sponsored by People For Bikes (PFB), a bicycling advocacy nonprofit out of Colorado. New York, Los Angeles, Austin, and Portland are among some of the other cities selected. The Big Jump aims to “achieve a dramatic boost in bike riding in specific focus neighborhoods within each of the 10 cities.”

One of the key components of the program is community engagement, and educating the teen ambassadors on all things biking is a large piece of that, Oyler says. “We can’t just put bike lanes on the street and expect that to be it. We really have to work with the people living in the neighborhoods.”

Sylvia Crum

Sylvia Crum

The city, in partnership with The Works CDC of South Memphis and Revolutions Bicycle Co-Op, recruited the teens for monthly training sessions, in which they learn safe bike riding, maintenance, and community organizing skills. In March, once the training is complete, each teen will receive a bike with a lock, lights, and a helmet. More importantly, Oyler says, the teens will become advocates for the Big Jump program and leaders of regular community bike rides. The goal, Oyler says, is not only to empower the teens as they lead the rides, but also to acclimate people to seeing bikes on the street.

Aside from community outreach, the Big Jump is unique in that it’s data-driven. “The city has done a great job in the past with building infrastructure and fairly quickly, but improvement is needed and what will be different about the Big Jump is data collection,” Oyler says.

As an early part of the initiative, the city’s first permanent bike counter was installed last month near Florida and Virginia streets, south of downtown. The counter sits under the street and counts each bike that passes over it, and eventually it will assess how that number changes over time as the street becomes more conducive to biking.

[pullquote-1]

Florida was chosen, Oyler says, because it’s one of the city’s few streets that serves as a good north-south connector between downtown and South Memphis. The data collected from the counter will not only help in decision making, but it will also validate and prove that people are riding bikes in the neighborhood, Oyler says.

“People have asked me, ‘Why South Memphis? People don’t ride bikes there. Why not Cooper-Young or Midtown?'” Oyler says. “But that’s wrong, and we now have data to show that.”

Since 2014, the city has been counting the number of cyclists riding through the intersection of South Parkway and Mississippi Boulevard. The first count, done prior to bike lane installations on South Parkway, showed an average of two riders a day. But, in the spring, the latest count showed around 122 cyclists each day. That’s about a 6,000 percent increase.

“To me, that says two things,” Oyler says. “One, when you put in the infrastructure to make it safer for riding, people will ride. And two, despite what some may think, people are already riding bikes in South Memphis.”

Big Jump sponsors, PFB, worked with Memphis in 2012 on the Green Lane project, which aimed to build protected bike facilities like those in Europe in U.S. cities. Oyler calls these facilities “all-ages infrastructure,” usable for all riding abilities.

But over time, the project showed PFB that a set of landmark bike lanes in a city is useless if they don’t make up a larger network in the community. “If you build one really nice bike lane that doesn’t go where people are trying to go,” Oyler says, “they aren’t going to use it.”

While the Green Lane project’s focus was city wide, the Big Jump concentrates on 20 square miles bordered by Mallory in South Memphis, Linden on the north, Riverside on the west, and Hernando on the east. In those designated neighborhoods, Oyler says, the aim is to improve connections and access to recreation, jobs, and education. “Obviously, bikes aren’t going to be the answer to everything, but if you can make it easier to get to these places by bike, then why not?”

Each of the neighborhoods will be used as a “proving ground” over the next three years, in which the city will try different approaches to make biking easier. The lessons that are learned in South Memphis will be carried to other neighborhoods around the city, Oyler says.

One of the next steps of the Big Jump will be to figure out how infrastructure improvements in the neighborhood should look, based on residents’ needs and preferences. Mississippi Boulevard is slated to be repaved with bike lanes in summer 2018, as the city works with the community to create a route connecting the south end of downtown to MLK Riverside Park, Soulsville, and other South Memphis locales. Forming the connection will begin next spring, when signage will be installed that directs riders from one neighborhood to the other.

Over the next 12 to 18 months, Oyler says, the route will be upgraded and repaved with protected bike lanes. “I don’t want people to talk about this as a bike project or program. I really see it as a community development program. While maybe the focus is on bikes, it’s really much more than that.”

One and Only

After Joshua was certain my helmet was on correctly, I joined him, his brother (also a teen ambassador), executive director of Revolutions Sylvia Crum, members of The Works staff, and Oyler for a Friday-afternoon bike ride through parts of the Big Jump focus area. We took off from the back of the South Memphis Farmers Market, a storage space The Works reclaimed for a fleet of refurbished bikes and helmets from Revolutions.

As we headed down Mississippi Boulevard, I rode on the back of a tandem bike with Gregory Love of The Works. Riding through the neighborhood, we passed churches, beauty salons, and a boarded window that read “believe in yourself” before reaching a small building marked by a bike hanging from the lamp post out front. Located across from the Stax Museum, the salmon-pink building — with old bikes and their parts scattered about inside — is being converted into South Memphis’ only bike shop. It is expected to be open for business sometime in 2018.

The next stop on our ride was at a two-thirds-acre farm near Lauderdale and Walker. It’s the Green Leaf learning farm, a signature program of Knowledge Quest, a nonprofit serving as a “community social change agent in South Memphis.”

In step with the Big Jump goals, Knowledge Quest will incorporate biking into its community agriculture outreach. A community-support agriculture program will be launched in the spring; it will hire teens in the community to regularly distribute fresh produce to residents via cargo bikes. A grant for the bikes was submitted to the state’s health department in late November, but Oyler says “because it’s such a cool idea,” even without a grant, it will happen.

As the sun lowered in the west, we made our final stop at Ida B. Wells — one of 15 schools across the city expected to participate in Revolutions Bicycle Co-Op’s Fourth Grade Bicycle Safety program, launching next fall. In partnership with the Shelby County School System’s (SCS) office of physical education, the program will teach the students how to safely ride a bike on on the street, giving them a reliable transportation option to get to school.

“They can try it when they’re in elementary school, then when they go to middle and then high school — which might be farther — they’ll have a good, safe way of getting there,” Crum says. “I thought when we talked with [SCS], we would have to convince them to do bikes with kids, but they were like ‘Of course we should.’ They immediately bought in.”

Downtown Elementary and LaRose Elementary, also in the Big Jump area, are two more of the 15 schools set to participate in the program.

Revolutions, located in Cooper-Young, is a nonprofit started in 2002 whose mission is to provide all Memphians, particularly the working poor, with well-functioning bikes. The co-op offers bicycle education and repair classes, bike services, and leads community rides. Revolutions has a retail store that sells refurbished bikes for reduced prices, as well as other accessories and equipment. They also have bikes available for rent.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Roshun Austin displays serious skill — and enthusiasm — for safe cycling.

Bike Share

As the Big Jump ramps up, one of its partner organizations, the nonprofit Explore Bike Share, is set to launch a bike-share system by spring 2018, in partnership with the B-Cycle Dash System, which operates 1,250 bike share stations with more than 10,000 bikes in 50 communities in the U.S. B-Cycle will bring 600 bikes to Memphis. They’ll be equipped with high-tech amenities, such as GPS systems with route recommendations and turn-by-turn directions.

Explore Bike Share, whose mission is to provide an inclusive and accessible bike-sharing system, plans for its 60 bike share stations to service high-demand areas such as Midtown and downtown, as well as developing biking communities like Binghampton, Uptown, Orange Mound, and parts of the Big Jump focal areas in South Memphis.

“From its inception, Explore Bike Share has vowed to prioritize neighborhood needs, utilizing the system to serve all of Memphis — not just where the city sees density on a map,” says Roshun Austin, executive director of the Works and an Explore Bike Share board member. “We are proud to execute equity-oriented strategies such as bike safety education, ambassador programs, and workforce development partnerships.”

By 2019, Explore Bike Share plans to add 300 bikes to Memphis’ fleet at 30 additional stations, thanks to a $2.2 million Congestion Mitigation Air Quality expansion grant.

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

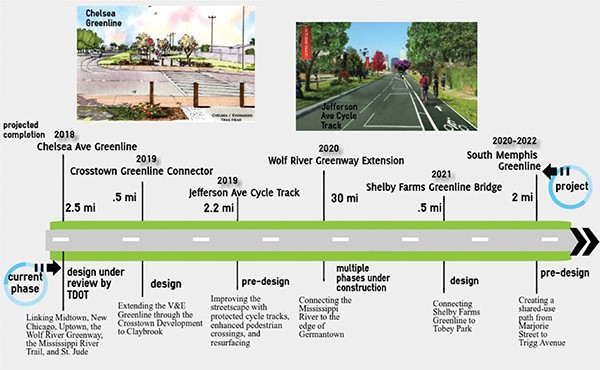

Potential Trails

The Path Forward

Oyler said he hopes as more Memphians are riding bikes throughout the city, the riders will be more “representative of Memphis’ population.”

For many Memphians living below the poverty line, bicycles can provide transportation equity, Austin says. “You may be initially getting on a bike for varying reasons, but when we did our community ride, people were coming from different backgrounds. Some were walk-ups from the neighborhood. They saw us and got excited and wanted to participate.”

Crum agrees, adding that cycling has to become more visible, with slow rides, group rides, and rides that connect from one neighborhood to another. “It helps all of us see people out on bicycles. And when residents see people who look like them out on bike rides, then the mindset starts to change to ‘Hey, maybe I could try that out.'”

If the goal is to get more people biking in Memphis, Austin says the city has to create a larger system of safe bike facilities. “You don’t build a house without a foundation. And infrastructure is that foundation for cycle transportation.”

Bike lanes smooth new riders’ transition to the road, says Lyndsey Pender, The Works’ research and evaluation specialist. “One of the barriers we encounter is fear of the road and sharing it with cars. I think bike lanes provide that confidence that some people might need initially, when starting to bike.”

Oyler says the city’s vision for the near future is to have a better network of safe bike facilities throughout the entire city. “For so long we have built our streets and neighborhoods around cars in Memphis,” Oyler says. “The only way that’s reliable, safe, and realistic to get around Memphis, for the most part, is by car — by design.

“If you look at a map of our bike lanes today, it’s disconnected, with a little piece there and a little piece here,” Oyler says. “If you imagine that those lines on the map were streets, you wouldn’t see that many cars, because what’s the point? You can’t connect. You can’t get to point A and B.” But, two to three years from now, he says there will be a “much better connected network of safe streets for bike riding, and as a result of that, more people will ride bikes for transportation, because it will become easier.

“There’s a saying among bike advocates that you don’t justify building a bridge by the number of people swimming across the river,” Oyler says. “You build the bridge, and then people start going across it, and that creates the demand. It’s the same with safe bike facilities and bike lanes. Until we have the safe infrastructure it will be a barrier to people.”

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens