For many years, you could often find me at 1580 Vollintine, in a sleepy strip mall in the Klondike neighborhood. There, at the juke joint known as Wild Bill’s, it felt like the party would never end. Many of us took out-of-town friends there. Cyndi Lauper, Yo-Yo Ma, and filmmaker Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu were among the many luminaries who visited over the years. Director Dan Rose shot a scene there for his underground epic, Wayne County Ramblin’ (featuring Iggy Pop), casting two-thirds of the Gories and Lorette Velvette as the house band. Everyone reacted with the same fervor: Wild Bill’s was unlike any other place on the planet.

“We had people from all different countries visit every weekend,” says vocalist and author Charles Cason, who emceed at the club. “I remember when I was performing at B.B. King’s, the tourists went up and down Beale Street and saw everything they needed to see, and then they’d ask where they could see pure, unadulterated down-home blues. We’d always recommend Wild Bill’s.”

In the early days, you flung the door open to Wild Bill himself — William Storey, a native of New Albany, Mississippi, who came to Memphis in 1937, started driving a cab in 1948, and began running nightclubs in 1964. He eventually opened Wild Bill’s in the early 1990s. Despite his sobriquet, Wild Bill was a somber cat. He’d eyeball you, hold up a number of fingers based on the size of your group, and once you handed over the cover charge, he’d slide off his stool and guide you past the band to a seat at one of the three long rows of card tables that lined the room.

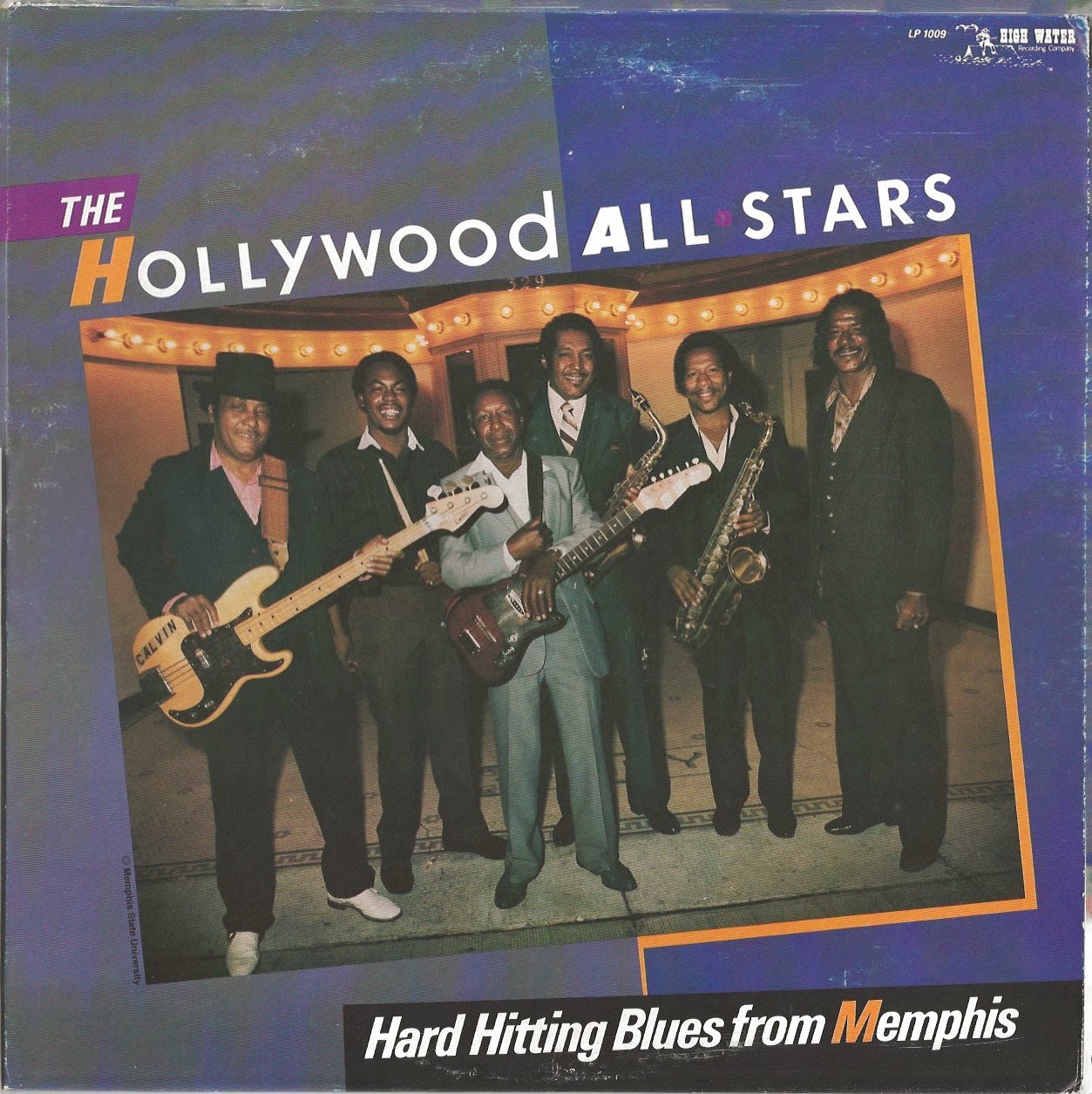

They sold cold 40-ounce beers and hot fried buffalo fish and fried chicken. When the dance floor got hopping, waiters Buddy and Mike strode up and down the room with giant plastic chitlin buckets, collecting tips. The band was typically an amalgamation of groups like the Hollywood All-Stars and the Blues Busters, with plenty of special guests and pick-up musicians thrown into the mix.

For a white person like me, Wild Bill’s offered a glimpse of a Memphis that others thought had dried up and blown away decades before. The smoky milieu was home to a unique black subculture, dominated by people of my grandparents’ generation — and I always felt welcome. Its proximity to the Rhodes College campus made it a haven for college kids wanting a taste of the real blues.

“Wild Bill’s was like church, with its own congregation,” says musicologist David Evans, who recorded most of the club’s musicians for University of Memphis label High Water Records. “In the 1980s and 1990s, there were a few clubs like that, but Wild Bill’s was just about the last one standing. These clubs were for the black community. White folks started visiting, and I think at Wild Bill’s, whites became a large factor, once they discovered it.”

The Hollywood All Stars on High Water Records

House guitar player Levester “Big Lucky” Carter died in 2002, leaving a large hole. Storey himself died in 2006, leaving the club to his wife, Lerlene, who ran the joint for several more years. Keyboardist William “Boogie” Hubbard, who had honed his craft backing up the likes of Memphis Minnie, passed soon after. And in 2012, effervescent bassist Melvin Lee died, leaving drummer Don Valentine as one of the few original members of the house band.

In more recent years, Wild Bill’s was run by a woman named Michelle (who did not respond to queries for this story). Around the first of the year, local stations ran stories about the club’s demise. According to news reports, landlord Rashad Alasdi pulled the plug on the venue because rent hadn’t been paid since last May. Cason contradicts that report, asserting that the property owner was actually behind on property taxes.

“It had to be something extremely crucial for [the club owner] to close at a time like that,” Cason says. “Here it was the weekend of New Year’s Eve. It was going to be a full house, wall-to-wall. And on December 29th, we suddenly got the notice that it was closed. The feds had enough consideration to call ahead and let her know that the taxes were way behind and they were coming to lock down Wild Bill’s. They suggested she carry out her stuff in advance — otherwise, everything inside the building would be confiscated.”

Evans laments Wild Bill’s closure, noting its impact on the local music community. “The musicians were part-time,” he says. “They made all right money, and most of the people who came to listen to them were their friends. It was also an incubator of talent, where younger musicians could sit in. Some musicians might have gotten their start at Wild Bill’s, or found the impetus to keep playing. Wild Bill’s kept Memphis blues going in the black community on a weekly basis.”

UPDATE, Feb. 17, 2018: Wild Bill’s Reopens.

Two days ago, Facebook followers were greeted with the following post:

“We’re baaaaaack! Come get your fill at the NEWLY REOPENED Wild Bill’s this Friday and Saturday night! Same great place, same crazy people, same cold beer, same hot music… only we’ll be starting a little earlier this time around for those of you who can’t wait to get dancing! Don’t call it a comeback. We been here for YEARS!”

The bar’s phone number remains disconnected, but by all indications the club has indeed been revived. Charles Cason, the emcee quoted above, was as surprised and delighted as anyone by the news. In celebration, we offer this tasty video from nearly twenty years ago…

Farewell to Wild Bill’s (Updated)