When asked about what makes a good wine, Irish-born Canadian wine guru Billy Munnelly of Billy’s Best Bottles always replies, “A wine that works for the moment.” This isn’t an exercise in short-sighted transience but a pairing of wine with a mood, more or less. As Munnelly says, “There is no ‘best’ — only ‘best for.'”

That’ll turn the role of the restaurant sommelier on its head — but I’m not sure that I can picture myself ordering chargrilled oysters and a big, mouthy Cabernet because it pairs well with my indignant malaise. The other side of the coin isn’t much better. Imagine being queried by the waiter, “I see that you’ve ordered the lamb, so tell me, are you suffering soul-crushing depression? Are you unusually horny, perhaps?”

Actually, the point to Munnelly’s approach isn’t so much about the wine drinker’s mood, but more the context of where he or she happens to be. Personal taste is very, well, personal; it is also maddeningly dependent on context. It is the same as having a music playlist for working out, which you’d never play during a candlelight dinner. So, if you pick a wine for the mood you are trying to establish, everyone will be happy. “The trick,” Munnelly writes, “is to stop looking at all the choices and start thinking about what you need.”

Granted, if you answer “I need to get drunk! And somewhat consistently!” then you ought to stick with vodka. Or an AA meeting.

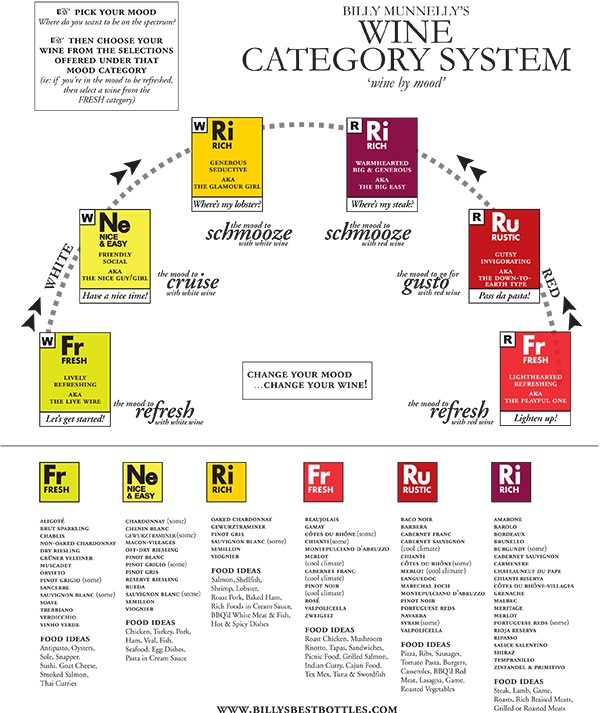

Munnelly has decided that there are three different “moods” for whites and, symmetrically, three for reds — and that almost every type of wine falls into one of these categories. It’s sort of a periodic table for winos, and it’s kind of brilliant.

“Ne” for Nice & Easy is a white wine category that includes Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, and Chenin Blanc — to name a few. Or, if you’re enjoying a rustic vibe, look under “Ru” to find suggestions like Côtes du Rhône, Syrah (some), and Merlot.

It’s an intriguing idea that isn’t as off the wall as it sounds. A recent study by Michigan State University assessed pairing certain wine categories (called “vinotypes,” because academics can’t leave well enough alone), not by food, but by certain innate characteristics of the drinker.

In Toronto, an “unwine bar” has opened up called Mad Crush, where the staff of aspiring sommeliers makes recommendations based on mood. And why not? To celebrate a victory there is a good reason to blow open some Champagne, as opposed to dousing one another in Barolo — no matter how “rich” it feels.

While wine as mood-enhancer is not a new concept, it does make you think twice about which moods you actually want to enhance. The danger here is not for the drinker, but the poor clod behind the bar and everyone within flanking earshot. After polishing off a couple of glasses “unaccountably chagrinned,” or “I just have sooooo much love to give,” the customer will almost certainly feel compelled to explain their particular mood to someone.

And you, gentle reader, simply do not care.