The Memphis City Council and the Shelby County Commission are 13-member bodies that meet with regularity, both in full session and in committee meetings. The way in which they both have come to operate might constitute a lesson of sorts to other legislative bodies supposedly higher up the chain of government. By that, of course, we mean the Tennessee General Assembly and the Congress of the United States.

The most direct contrast to those more rarefied legislative entities can probably be supplied by the county commission, because it, like the Tennessee legislature and the U.S. House and U.S. Senate, is elected according to the dictates of the two-party system, which pits Democrats against Republicans in electoral contests and thereafter requires the representatives of either party to sit in common assembly.

Increasingly, the commission provides a textbook example of how the two-party system is supposed to work. There are conflicts, sometimes ferocious ones, but these develop more often according to personality than to party lines. Differences that arise from the ideological divide of the two parties occur, of course, but they are usually resolved by the simple arithmetic of a vote-count (abetted in no few cases by some artful vote-trading).

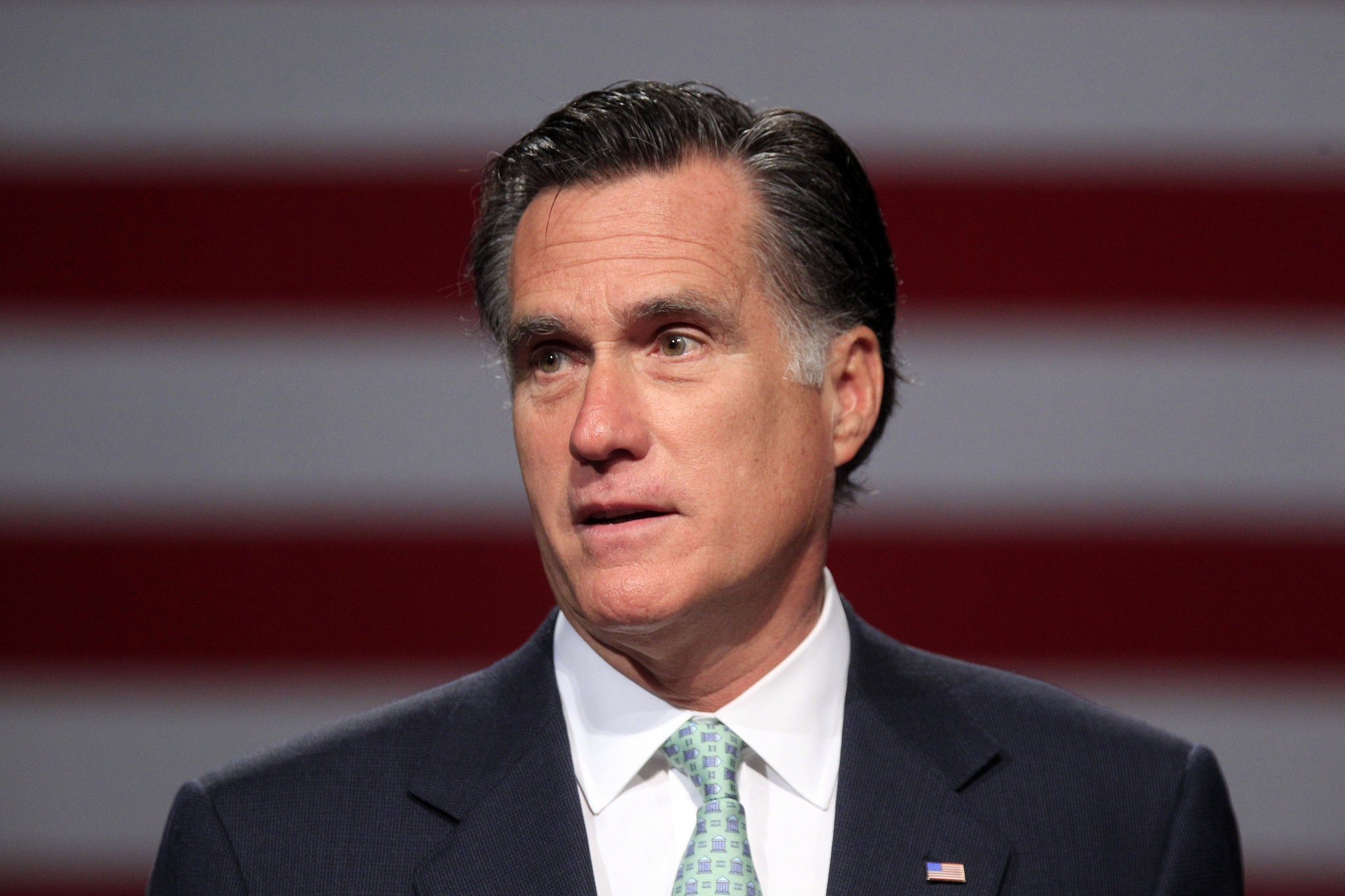

Mitt Romney, father of Obamacare

After a stutter or two a few years back, the commission has resumed its “gentlemen’s agreement” tradition of rotating its chairmanship back and forth by party. This year’s chair, elected on Monday, is a Republican, Heidi Shafer, who succeeded Democrat Melvin Burgess.

During this past year, the members of the commission concurred across party lines on matters ranging from minority contracting to taxing philosophy to the essentials of a long-term “strategic agenda.” It is hard to make direct comparisons to the General Assembly, where the ratio of majority Republicans to minority Democrats is wildly disproportional, but the two houses of Congress are balanced enough between the two parties to allow for instructive contrasts. Rather infamously, the two-party system there is totally dysfunctional, and “gridlock” is too kind a name for it.

The nation has just witnessed the spectacle of one party in the Senate trying to abolish the nation’s prevailing health-care insurance system — and recklessly, without a real alternative. The scheme failed only because three members of the majority party were conscientious enough to scuttle it, calling instead for bipartisan action and consultative reform efforts.

What made the shabby repeal effort doubly ironic was that the Affordable Care Act, so tenuously rescued from Republicans acting in near-total lockstep, had been inspired by a Republican think tank and a Republican governor, Massachusett’s Mitt Romney, in the first place. The congressional GOP’s fanatic resistance to the act had been based on nothing more, ultimately, than a nakedly partisan pledge made eight years ago to oppose anything and everything offered by Democratic President, Barack Obama.

Now that Obama is out of office, that sordid motive is obsolete. Going forward, two parties, like two heads, can be better than one. But only if they genuinely take heed of each other.