As he poses for a new photo, leaning against a tree with his guitar, tall and slender guitarist Kenny Brown looks pretty much like he did in old photos of himself in his twenties performing with blues legends.

“I’ve weighed between 130 and 160 since I got out of high school,” says Brown, 68.

But then he adds, “Somebody told me the other day — we went down to the coast — something about my skin looking so good. That’s the only person who ever told me my skin looked good. Hell. My hair iscoming out. Growing out my ears and nose and falling off my head.”

Though his hair is falling “off his head,” Brown’s musical ability continues to grow. The latest proof? Brown is nominated, with The Black Keys and Eric Deaton, for a 2022 Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album for Delta Kream.

“[The title] ‘Delta Kream’ came from a William Eggleston photo of a Delta Kream custard stand down in Tunica,” Brown says. “Eric Deaton plays bass and I play guitar. The way it happened was, Eric had done a couple of records with [The Black Keys’] Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye studios in Nashville. They were doing a Robert Finley record and they asked me to play on it.”

They finished that record in two days, but Auerbach asked Brown and Deaton to stick around for a couple more days. They recorded Delta Kream.

That serendipitous recording session was no fluke; Brown has a history of finding himself in the right place at the right time.

Must Have Been the Right Place

Brown recorded his debut album, Goin’ Back to Mississippi, in 1995 with Dale Hawkins in Little Rock, Arkansas, but his list of bona fides is long. Brown played on albums with blues legends R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, Paul “Wine” Jones, and CeDell Davis, all of which were recorded for Fat Possum Records based in Oxford, Mississippi. That was also where Brown recorded his solo album, Stingray.

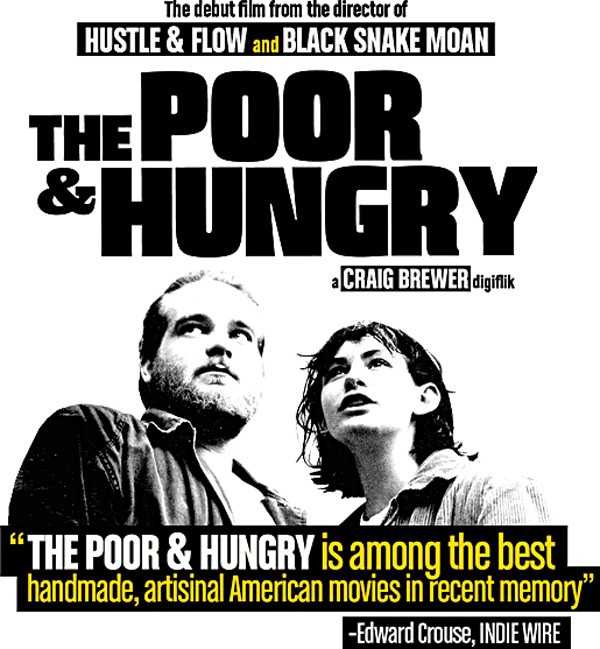

He performed in the 2006 movie, Black Snake Moan, which was written and directed by Craig Brewer. In addition to backing Samuel L. Jackson’s singing, Brown appears in the film as a blues band guitarist along with his buddy, Grammy-nominated drummer Cedric Burnside.

“I was always a big fan of Kenny Brown,” Brewer says. “I am a fan of that whole early Fat Possum era that he was a part of. I think why I love him and everybody loves him, is there’s a great craft in the way he plays. The older I get, the more I tend to appreciate that. It’s authenticity. He’s playing what he lives. He’s playing what he knows and you can feel it. It’s more than just hearing it. You can feel it. There’s only a handful of artists that can do that. And he’s one of them.”

Raised on Radio

Brown’s mother was spot-on when she wrote about her child in his baby book. “She said that I was crazy about guitars, guns, horses, and cowboys,” Brown says. “I still am.

“The first time I remember hearing any music was getting in my parents’ car in the early ’50s,” the musician remembers. “I was laying in the car getting ready to go to church and hearing, I guess, a Johnny Cash song. I grew up watching the Ozzie and Harriet show with James Burton and Rick Nelson playing. There were some country shows that would come on like Louisiana Hayride.”

Brown also listened to a blues station late at night with a friend. “We’d sneak out in the car and lay down in the seat and turn on the radio and get that Nashville station,” Brown says, remembering that he didn’t need the car key if the car was put in “lock.”

Growing up in Nesbit, Mississippi, Brown remembers when he heard his first blues fife and drum band, a style of music with its roots in African drumming, military fife and drum corps, and blues influences. “I was out in the yard playing one day and I heard this music. I couldn’t tell where it was coming from, and it was getting closer and closer. I looked and there was this truck coming up the road and there was this fife and drum in the back of the truck,” Brown recalls. “That’s how they announced the picnics. Not everybody had phones [at the time]. They turned right across the road from my house. There was this guy who had picnics right across from the house.”

Brown didn’t get to go to them, but the picnics fascinated him. “I would lay in bed at night. Sometimes they’d play all night long and party all night.”

The music took root in Brown’s mind, and he got his first guitar when he was 10 thanks to a business venture with his brother. “You could order seeds from the back of a comic book. We ordered a bunch of seeds and we rode our bicycles selling garden and flower seeds to the ladies around us,” he says.

The Brown brothers won prizes for the amount of seeds they sold. “I got a little plastic guitar that would tune up and had a book with it. I think my brother got a BB gun,” he remembers.

Brown taught himself to play the guitar, which had “little catgut plastic strings,” by reading the book as well as listening to the radio “trying to figure out stuff.” He also took some lessons.

One day his mom surprised him with a real guitar. “A Kay archtop acoustic guitar with the F holes and stuff,” Brown says.

In another right-place, right-time moment, blues guitarist Mississippi Joe Callicott moved next door when Brown was 10. “His house was probably not 100 yards away. I could hear him sitting on the porch playing.” Brown’s brother said, “You ought to go over and see Joe.”

Brown and Callicott played “When the Saints Go Marching In” and other gospel songs. They also played blues songs, including “Frankie and Albert.”

Callicott gave him pointers. “He’d say, ‘Hit it like this, boy.’ And he was singing songs. All that got me really interested. I hung out with him almost every day.”

Conjuring Brewer’s comment about authenticity, Brown muses about the heart of blues music, saying, “It feels so good. And it’s real music — comes from the heart. It’s hard to describe. People just get feelings for different things.”

Brown, who plays the “North Mississippi hill country blues” style, says, “The hill country stuff kind of fit. Maybe from growing up around here, I don’t know. People always ask me to describe ‘hill country.’ I just tell them, ‘Don’t try to analyze it. Just feel it.’”

“Some of That Stuff”

As he got older, Brown began meeting other blues players, including Jim Dickinson, Sid Selvidge, and Lee Baker. “Sometimes I think I was better when I was 18 than I am now,” he says. “I guess ’cause I didn’t know anything. I’d just do whatever I could do. I was so hungry for it back then, I guess. I was a slow learner, but I just tried to learn from everybody I could. I never expected to make a living at it.”

A friend who had a rock-and-roll band hired R.L. Burnside to open for him. Brown introduced himself and said he liked what he was doing and wanted to learn “some of that stuff. He told me where he lived and I started going down there and playing.”

They played together at juke joints, picnics, and other events “for 30 years until he quit playing. For years, I’d just play around his house or go to picnics or juke joints.”

R.L. took him to his first juke joint, Brown says. “It was a juke joint way out in the sticks somewhere in Panola County.”

It was “just an old house in the middle of nowhere. Seems like we drove down one of the wooded roads that was like a tunnel for 20 miles. All the trees have grown together above you. We came to a house. There was nobody there for 30 minutes. As soon as we started playing, it filled up. I don’t know where they came from,” he says.

“We got to playing. And they were gambling in the back room. All Black people. I was the only white person there. It was the first juke joint I’d really been in. We were playing for a while and R.L. said, ‘You keep playing. I’m going in the back and gamble some.’ I said, ‘R.L., don’t do that. They’ll kill me out there.’ He said, ‘I think you’ll be all right.’ He lost his money and came back. I kept playing and people loved it.”

Brown went on to play gigs with other blues performers. “We used to play a lot of picnics and little juke joint house parties. Sometimes I’d get with Johnny Woods and pick him up Friday and start driving and go to different house parties and stay gone all weekend.”

Music was a side job at first. “I made decent money doing construction, being a carpenter. That way I could afford my habits — going to the juke joints and stuff to play.”

Juke Joint Caravan, Hill Country Picnic

Brown began touring after he met George “Mojo” Buford on Beale Street. “Hit it off with him and we got to playing. We did a tour up to Canada and the East Coast and ended the tour in Clarksdale on Muddy Waters’ birthday.”

Brown invited R.L. to sit in with the band at the Clarksdale show. R.L. arrived with Matthew Johnson, founder of Fat Possum Records, where

R.L. was recording.

A couple of weeks later, Johnson called Brown and said they wanted him to play on R.L.’s record. They said, “We love his solo stuff, but we want it to rock a little more.”

They recorded R.L.’s album, Too Bad Jim, with drummer Calvin Jackson the first day. Then Brown played on Junior Kimbrough’s album, Sad Days, Lonely Nights. They were recorded at Junior Kimbrough’s legendary now-gone juke joint near Holly Springs, Mississippi.

“I love Kenny,” Johnson says. “I was lucky to be around a lot of great people, but I put Kenny at the top of the list.” Of Brown, whom he calls “a savage guitar player,” Johnson says, “We wouldn’t have Fat Possum without him. He was so vital in the creation of the label.”

Plus, in a nod to the seemingly mundane but practical details that can make or break a burgeoning music career, Johnson says, “He had a van. He had a driver’s license.”

After they made a record, they had to get out and promote it, Johnson says. “You got out there and beat the hell out of the road if you’re going to make it. And we did that. We toured nonstop.”

After they did the Fat Possum albums, Brown and R.L. were invited to play a gig in Canada. They needed a drummer. R.L. said, “I’ve got a grandson who plays pretty good.”

That was Cedric Burnside, whose Grammy nominations include Best Traditional Blues Album in 2019 for Benton County Relic.

“We would go out for two weeks at a time. We’d have me and R.L. and Cedric and T-Model Ford or Paul ‘Wine’ Jones. We’d have a vanload of people. A lot of times they called it the ‘Juke Joint Caravan.’”

And, he adds, “I think I counted up one time. I’ve been to every state and, I think, something like 12, 15, 17 countries.”

Brown began the iconic North Mississippi Hill Country Picnic 16 years ago. “I’d been traveling all around the world, seeing all this interest in this style of music. I think they began calling it ‘hill country’ music by then. People were loving it everywhere we went, but nobody was doing a festival here in Mississippi focusing on that type of music from the region.”

The first Hill Country Picnic was held in a pasture in Potts Camp, Mississippi. The stage was a flatbed trailer. About 1,000 people attended the picnic, which was organized by Brown’s wife, Sara. “All we did was send out maybe 100 emails.”

Brown later had a permanent stage built at the picnic’s current location between Oxford and Holly Springs. One year, Brown says, the two-day event, which is held the last full weekend in June (June 24th and 25th this year), drew 3,000 people from 38 states and 11 countries. “I wanted it to be like the old-style picnics where there was plenty of food and drink and good hill country music.”

Farther from home, Brown plans to attend this year’s Grammy presentation on April 3rd in Las Vegas. “I hear all the time people are booking gigs and asking if they’re Grammy-nominated. I don’t know. I hate to say it’s not a big deal ’cause I guess it is. But I don’t know how much my life will change.”

For now, Brown says, “I’m doing a tour with The Black Keys this year. It’ll be fun. Decent pay.”

Brown, who lives near Potts Camp, says, “I’ve got a big barn over here next door to my house with a big living area upstairs I’m trying to convert. We set up some recording equipment in there. I’ve got a project I’m trying to get done there. There’s a record by a pretty big country artist that I played on that’s supposed to be coming out in April, but I’m not supposed to tell who. I’ve got some songs put together good enough to record them. And digging out some old stuff to record. And trying to get everybody lined up, find the right people to record them.”

He’s written original songs over the years as well. “I write ideas down all the time. Lot of times I get them during the night,” Brown says, “and if I don’t get up and write them down, they just keep flying through the air and somebody else gets them.”

Last Kind Word Blues

Brown has watched his old friends and mentors die. He was 15 when his next-door neighbor Mississippi Joe Callicott died. “His wife told me he rolled over and his last words were, ‘Kenny be a good boy.’

“I hated to see him go, but he had gone downhill some. None of us are getting out of here alive. Hell. It used to be I was the youngest one hanging around all these guys like Bobby Ray Watson, Johnny Woods, and R.L. Burnside. Now I’m one of the older guys.”

Brown once visited a psychic at a health food store. “He told me my purpose on Earth was to raise the vibratory rates of the human race through music. I don’t know how many people he told that to, but I was one of them. He didn’t know I played music. That was kind of a weird thing that he could actually tell that. He could have been making it up and it could have been all bullshit.”

But, Brown says, “We were on stage in Santa Fe, New Mexico, one time. The place was packed wall to wall. T-Model and R.L. were doing the show. And every face that I saw had a smile on it. And I thought, ‘Maybe he was right.’”