Even today you can look to any random corner of my bookshelf see where forGET SOMEthing came from. But what matters is where it didn’t come from.

Like many fragile, anxiety-ridden white men in America today, I worry that my decades-old experiments with blackface will go public. I fear the fallout will be catastrophic and am concerned, even now, that my opening sounds too much like some ironic personal essay plagiarized from McSweeney’s. Because, I’m not really afraid. But in this moment, with America browsing old middle school annuals and memory books — artifacts memorializing our intimate histories better than a journalist ever could — I wonder if there’s some value in reviewing my own worst judgment as an author and artist? It’s good to see better and more honest dialogues about privilege filtering out beyond academics, as the idea sinks into popular consciousness. But privilege has helpers and component parts and if we’re ever to dismantle all that, maybe it’s not a terrible idea to reflect on seduction, pride, nostalgia, and all the intellectual blind spots and emotional investments that can make glaring insensitivities seem like no big thing — that can make biases impossible to self-diagnose and easy to manipulate.

[pullquote-1]Unlike so many U.S. high school graduates (apparently), I never did “blackface.” I did something much worse. In the 1990s, when I was a young artist working outside the mainstream and trying my best to get noticed, I wrote and produced an arty little play requiring three other white actors to wear the burnt cork. I wanted to offend. I wanted to shock people out of complacency and cause a damn riot like Alfred Jarry, the French pataphysician who infuriated audiences with the first word of Ubu Roi. Could theater even move people that way anymore, I wondered before embarking — with open heart, purest intentions, and a crew of mostly white friends — on a consequence-free journey to none of the answers.

Shortly after graduating from college I decided black people were imaginary. Not literally; it was how my angry, artist’s brain processed being poor and powerless and almost as shocked by the things I saw daily in the street, as I was my own relatively high standing in the social order. It was impossible not to notice discrimination everywhere, not to mention the politicized drug war and urban development that hid and warehoused people. More relevant to the second-most racist thing I ever wrote, as a college student studying communication theory and history, I’d grown to believe that a monolithic media culture folds images of minority life — including those of struggle and overcoming — into a vast white supremacist fantasy. This fantasy (that I now document as a media writer) is what I meant by “imaginary.” It wasn’t hardly “woke,” but I might still be proud of those big ideas today, if I hadn’t expressed them so profanely and illustrated them in my script with a minstrel show.

Of course I didn’t stop to reflect on the absence of black representation in my own process — Welcome to the 1990s. Hindsight will cut you.

It’s gonna get nerdy in here, but only for a paragraph. In his book The Theatre and Its Double, Antonin Artaud imagined ways theater might be more like painting, and I ate that stuff up, even though I didn’t totally understand it. I drifted into performing arts as a teenager, partly because I wanted to be a visual artist but had little aptitude for it. So it came to pass, enraptured as I was by grotesque figures in Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights,” and drunk on Post-structuralism, I wondered if I might be able to make tiny plays that worked like a painting montage, using nightmare images plucked right out of the American dreamtime? Could I spin media tropes, religious iconography, a spectrum of kitsch and other mass replicated images into a comic vision of hell on Earth, where nothing good can ever be obtained absent a focused and sustained period of humiliation?

Dude.

The second-most racist thing I ever wrote was a brief, surreal farce about the rituals associated with getting a job from “Help Wanted,” and entering “normal,” adult life. A woman played the leading man; a man played the leading lady; and my script featured a two-faced villain lovingly crafted to remind the audience of every slick infomercial they’d ever seen, and of every shitty boss they’d ever worked for. The plot was borrowed entirely from the Bible, and opened with the most shocking image I could imagine: A pair of blackface actors forced into an eternal game of kicking each other in the ass. I named the 40-minute skit forGET SOMEthing after a promotional sign I’d seen hanging in a fast food restaurant that spoke both to my Gen X sensibility and to an idea I couldn’t shake: We’re not allowed access to “normal,” without participating in rituals so reprehensible we make ourselves forget instantly. Then somewhere between all the getting and forgetting we stop being able to differentiate between the rituals and their promised rewards.

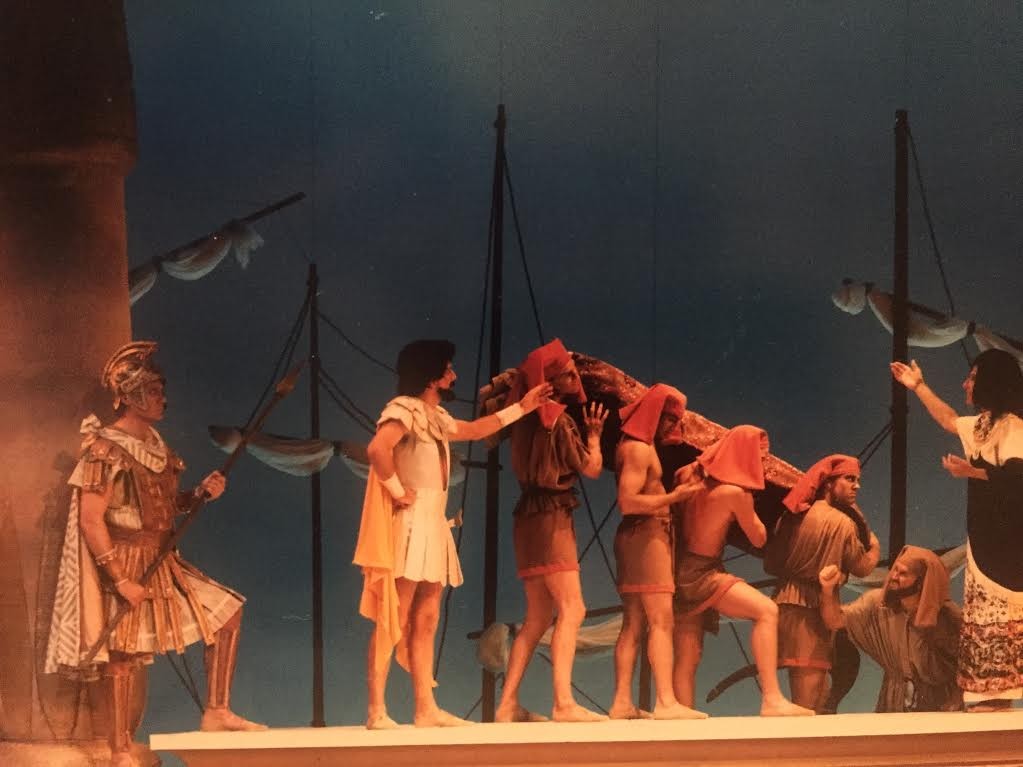

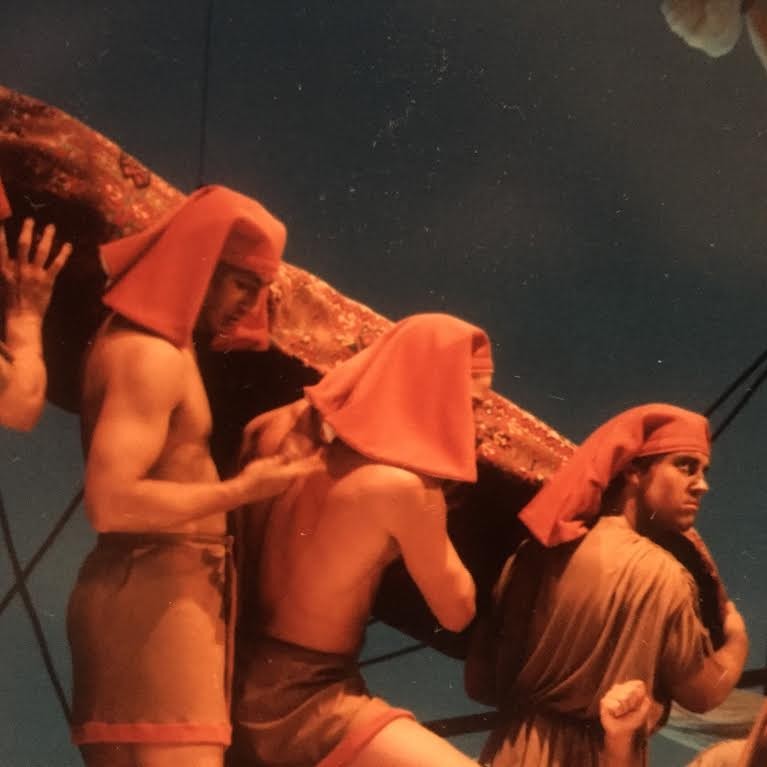

Theatre Memphis’s 1980s-era production of Caesar & Cleopatra.

forGET SOMEthing was heady, no doubt. It was angry, full of extreme imagery and lots of reliably hilarious scatology. The climactic line “There is some shit I will not eat!” marked a dramatic turnaround as the doomed hero pushed back against his/her abusive boss Mr. Peelum, and his disgusting demands of fealty. With this unlikely battle cry, all “traditional” things in the show were liberated. The audience cheered and cat-called when Adam shed his boyish cocoon to become a fully grown (and mostly nude) woman with fig leaves in all the appropriate places. The crowd responded similarly when Eve, a receptionist so underpaid he/she moonlights as a phone sex operator, swapped genders and approached her counterpart as in this famous picture of the artists Marcel Duchamp and Brogna Perlmütter. When it looked like old man Peelum was vanquished for good and some strange paradise was finally possible, the bad guy came back to life, transformed into the Satanic partner Mr. Edom, to murder Eve/Adam, crushing all hope for a happy ending.

“I’m the boss,” Mr. Edom snarled triumphantly, as the decorative heart Eve wore around her/his neck pumped blood across the stage. “You can’t get rid of me. All you can do is change my name.”

Scene.

I suppose it wasn’t all Artaud and Ubu. The Who snuck in there in at the end, and, adding insult to irony, I imagined the whole enterprise to be a kind of love letter to Douglas Turner Ward, whose white-face comedy, Day of Absence, is one of the great American plays.

Now that the stage is set I should do a bit of housekeeping. Like, if forGet SOMEthing is the second-most racist thing I ever wrote, what’s the first? “Steal This Flag” is an essay born in fragility and out of my frustration with intractable public debate over Confederate iconography when action seemed necessary. If the rebel flag-huggers wouldn’t peacefully lay down their red white and blue security blankets, the next step was obvious — Somebody had to take the flag away. Somebody (read: African Americans) should appropriate that oppressive iconography, bear all its shameful weight, and change the flag’s meaning so completely that racists can’t recognize or accept it as their own. Radical, right? But strip that column to its skivvies, and what have you got but another white reporter telling black folks that racism is their mess to clean up? Chop chop, black folks: time’s a-wasting.

“Steal This Flag,” found an audience and got my hand shaken by many sensible and successful white people. And speaking of bullshit, I’m only able to say I’ve never performed in “blackface” because it’s my entire body they painted brown.

As America continues to pore over her recent past and an Old South kept forever young in the autographed pages of our high school yearbooks, I additionally wonder about all the kids whose intolerable stage moms signed them up to play Siamese children in community theater productions of The King and I. I think about the musical theater kids who painted themselves red and spoke broken English as one of the native Americans in “family-friendly” entertainments like Little Mary Sunshine or Annie Get Your Gun. Or the ones who landed one of those plum yellow-face “comic relief” roles in their high school’s beloved production of Anything Goes. This was the wholesome stuff, and it’s been everywhere.

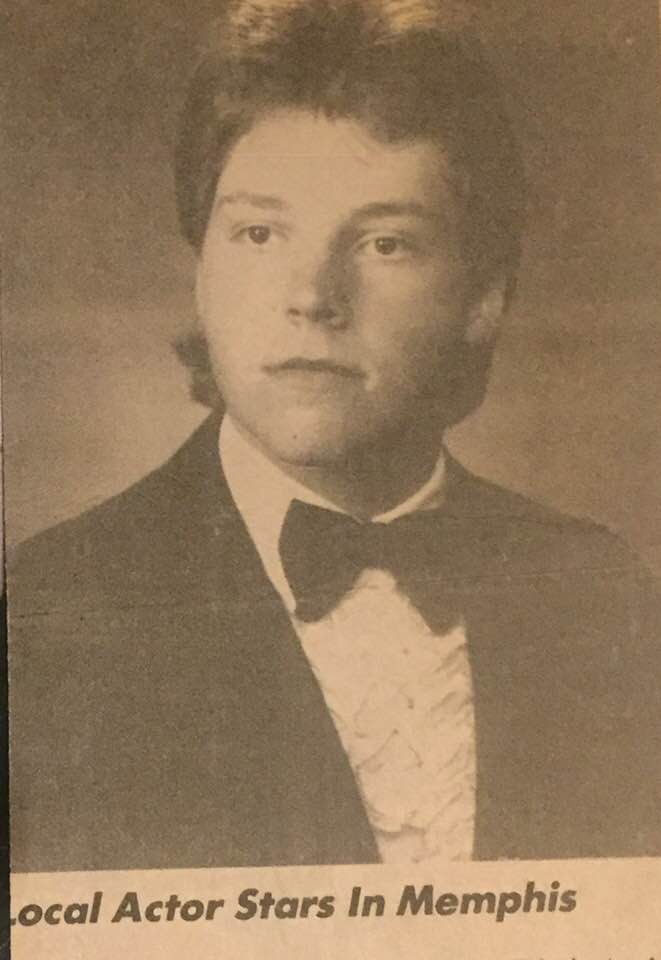

I think about another teenage ritual that took place on stage: “slave auctions,” the annual homecoming event where varsity athletes were sold to the highest bidder to perform reasonable, between-class labors for a day. Then there’s that one weird time when I was 19 and so damn excited to be cast in my first big costume drama on the main stage at Theatre Memphis, I didn’t bat an eye when director Sherwood Lohrey told me to shave off all my body hair because I’d be playing Egyptian and naturally they needed me smooth and bronze from head to toe.

Naturally.

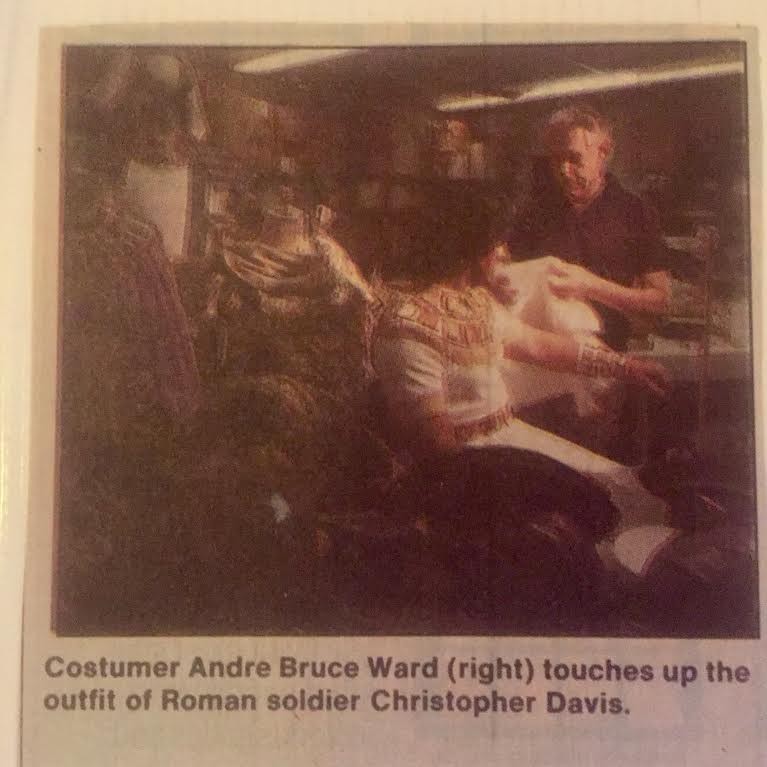

The smooth, bronze show in question was G.B. Shaw’s, Caesar and Cleopatra and to promote Theatre Memphis’s lavish costumes, a full color photograph of me being made up and dressed, appeared on the cover of the Commercial Appeal’s entertainment section. It was 1987. Not yesterday, but modern times by anybody’s accounting, and I don’t think a soul working for the theater, or the newspaper, gave my afro-wig a second thought. So I didn’t either.

Dammitt Gannett (even though Gannett didn’t own the Commercial Appeal in the 1980’s). I was an EGYPTIAN soldier. The Romans didn’t have to shave their bodies, paint themselves brown, or wear afro wigs!

To my great disappointment/relief, nobody rioted when forGet SOMEthing opened at an art gallery in Memphis’s Edge district. Instead, pale denizens of the gallery scene belly laughed, snorted, and rewarded my bad behavior with crazy applause. I was a hit, and toasted by academics (who invited me to sit in and talk to their classes), and tastemakers (who invited me to dinner!) About year later I revived the sketch for another group show at a different downtown art gallery. [pullquote-2]

Word was out for the second show. The sweaty upstairs gallery packed fast and got crazier as the night went on. People had been drinking, and once the show started, everybody laughed and hooted so wildly I couldn’t hear or follow my own dialog. When the crowd laughed at the clowns — totally unable to hear a thing being said — I got the sickest, sinking-est feeling in my gut. Listening to all this instant feedback — the kind of uncontrollable laughter every wannabe playwright dreams of — I started to think that maybe I’d made an awful mistake. I still believed in what we were attempting and was proud of the actors and what we’d done together. But now a big chunk of me wanted to make the whole thing disappear forever. Instead of disappearing, a Memphis art magazine called Eye (now disappeared) ran a glowing feature and an interview with the local musician/actor who played twin villains, Peelum and Edom. I was mad that they hadn’t spoken to me because I wanted credit. Or blame. Basically, I wanted to start the explaining.

The guy all the way down right looking all mad? Me.

forGET SOMEthing marked the beginning of the end of my time as a producing artist. A few more original scripts made it to their feet and I spent a couple of years working through the Center for Independent Living, making art and activist theater available to people living with brain trauma, autism, Down Syndrome, and various other cognitive and physical challenges. But I mostly worked on other people’s projects before applying for a receptionist’s position with Contemporary Media, and accidentally becoming a professional critic.

Dennis Freeland, the Memphis Flyer editor who made me a full-time writer, called me into his office one day to scold me for writing “like a regular reporter.” It’s probably why I still feel compelled to invest time in pieces like this one. He said he wanted me to go big and weird and take risks and do what I could to tell Memphis’s story in ways you can’t approach using a reverse pyramid style. He wanted gonzo stories like the “Adventures of Shirtless Man,” and hot takes in the vein of my weird plays, and occasional forays into storytelling and performance art. So, even as a writer who matured in a liberal petri dish, when I look back at the stepping stones, I have to acknowledge the presence of supremacy and exploitation. It’s no excuse that I was raised in practical segregation and came of age working in a medium that still makes a regular practice of yellowface, blackface, and expedient erasure. But I’m not making excuses. Even it I wanted to, modern controversies related to bad judgment and vintage photos, aren’t well-answered with whys or wherefores. They’re part of a messy, overdue process of discovering whether or not we’ve learned anything since.

The Second-Most Racist Thing I Ever Wrote

I‘ll close with a memory that’s time-embellished, but as close to a picture of the truth as I can paint. It all starts with an old high school friend standing beside her broken-down car on the shoulder of Highway 13, somewhere outside of Clarksville, Tennessee. She was going to Nashville to audition for a nationally televised lip-synch contest called Putting On the Hits. It was the mid-1980’s, and my friend’s brown hair was frosted and teased high. One red stiletto heel was ruined, and mascara streaked her cheeks and stained her denim jacket. After coming to her rescue with another friend in tow, the three of us took my car to a convenience store where we bought White Mountain Coolers and Pink Champale, then drove to a nearby creek to sit fully clothed in the water and toss a pity party because misfits like us never catch an even break. My friend sobbed because she thought she’d let everybody down, especially Tina Turner, and the darker-than-normal makeup she’d worn to look like her favorite singer, ran in the cold current. There, in the middle of that creek, with, “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” blaring from the nearby car’s speakers, she performed her lip-synch routine for us, and in that twisted John Hughes-moment we were all as good, and loving, and perfect as three underage kids drinking and dreaming their hearts out can be. But here’s the twist folks: I’m not playing this conclusion for sympathy. That sweet picture is the strongest evidence of corruption I can conjure.

Now that I’m done with all this, I almost forget the point and don’t know for sure that I made it. I think it all had something to do with how surprised I was by everyone’s surprise at all the casual racism that went down during the best years of our lives. It’s not like we weren’t all there the first time.

The news from back home. Also, the 1980s.