Thirty-four turned out to be Mario McNeil’s unlucky number. The 34-year-old African-American man and a friend headed to a favorite hangout, Divine Wings and Bar, the afternoon of March 16th. As the men entered the restaurant, an assailant opened fire on them. According to eyewitness accounts, the gunman jumped into the passenger seat of a Chevy Lumina and sped off. McNeil’s friend survived the attack. Paramedics rushed McNeil to the emergency room at the Med, but McNeil died as the result of gunshot wounds. He was the city’s 34th homicide victim of 2007.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

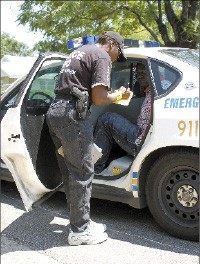

Operation Blue Crush targets crime hot spots around the city and uses police resources to reduce illegal activity.

Police describe the suspect in the shooting as an “unknown black male.”

The vast majority of murders in Memphis are of the so-called black-on-black variety. The annual number of these crimes has grown from 83 in 2004, to 99 in 2005, to 106 in 2006. These totals account for 65 to 70 percent of all homicides in the city each year.

The Memphis Police Department (MPD) made a staggering 102,000 arrests last year. Yet the homicide statistics as a whole, and the black-on-black murders in particular, have swelled. MPD has instituted a new, technologically sophisticated strategic tool. Now Memphians will see if a new system of crime-fighting can suppress an old problem.

The city has battled its bloody image for over a century. An editorial in the October 10, 1870, edition of the New York Sunday Mercury included the line “to those desirous of shuffling off this mortal coil, to those weary of life, but who have not the courage to shoot or hang themselves, we recommend a trip to Memphis.”

In the early 1920s, a statistician for the Prudential Life Insurance Company named Frank Hoffman dubbed Memphis “murder-town.” Mayors Rowlett Paine andS. Watkins Overton financed research and publications debunking both the claim and Hoffman’s annual rankings of America’s bloodiest cities. While the mayors found plenty of caveats to attach to Hoffman’s numbers, neither could dispute the high total of homicide victims in the city.

Unable to solve the problem of violence, the city’s public-relations efforts turned to consolation. A headline in The Commercial Appeal in September 1928 spoke directly to the fears of a violent, racially split city: “Few Negroes Kill Whites.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Richard Janikowski

That trend has held firmly. The stubbornness of residential segregation and the nature of crime in general, and of homicide specifically, have kept interracial murder rates relatively low in Memphis. MPD statistics list 15 homicides involving white victims and black suspects in the three years from 2004 to 2006.

Public attitudes on the issue of black violence in Memphis can be difficult to gather. Reporters asking questions tend to put folks on their best behavior. In the relative privacy of online communication, however, observers of black violence in Memphis speak openly.

An article on WREG.com entitled “Black on Black Crime Growing in Memphis,” which included homicide statistics for the first half of 2006, was posted on the American Renaissance Web site last year. American Renaissance is a self-described “publication of racial-realist thought.” Readers of the site are able to leave comments about articles posted. The responses to the black-violence article revealed a wide range of reactions to the problem.

One post reflects a misperception: “[B]lack on white crime is actually more common … nobody ever even mentions black-on-white crime.”

Another says, “It’s because of the stats like this that the locals near Memphis call the place ‘Memphrica.'”

Many commenters left messages similar to this one: “Well, white folks certainly DO have a stake in this, but how is it their responsibility? How is the weight on them? What are they supposed to do, walk around the city waving their fingers sayin’, ‘Now, now — don’t you go killin’ nobody.'”

Another sums up the frustration with standard — albeit disempowering — explanations: “It’s been said before but deserves to be said again. You can’t put all the blame on poverty, that’s way too simple.”

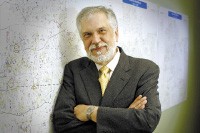

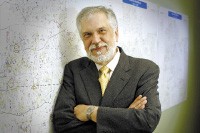

Richard Janikowski chairs the criminology and criminal justice department at the University of Memphis. As the architect of the much-ballyhooed operation Blue Crush, Janikowski hopes to bring Memphis policing strategy from behind the curve to the cutting edge.

Blue Crush is the local version of data-driven policing programs like CompStat in New York City and I-Clear in Chicago. MPD implemented Blue Crush operations beginning with a pilot program in August 2005, and the program went citywide last October. “The entire guiding principle behind Blue Crush is to get the right resources into the right place at the right day and right time,” Janikowski explains.

“There are criminologists around the country who say that the only way to cure crime is to cure all social problems,” Janikowski says. “This is the old ‘root causes’ thing. The lesson of the last two decades is that we can affect crime without affecting the root causes. Police make a difference. We can use innovative techniques to suppress crime.”

Blue Crush takes a geographic approach to fighting crime. It locates concentrations of offenses in a given area and charts the day, time, and nature of offense. “We track arrests … and look at Part I crimes [murder, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, motor vehicle theft, and arson], the most serious offenses, reported to the FBI,” explains Janikowski, though Blue Crush does not target homicide.

The program also does not track the race of an offender. “[Ethnicity] doesn’t directly figure in the data,” Janikowski says. “The reality is that [with] arrests in Memphis, just like nationwide, the overwhelming number identified in criminal activity are young African-American men.

“Geography trumps ethnicity,” he says.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

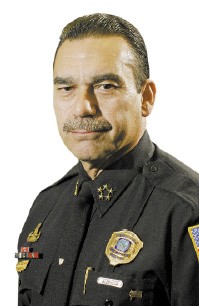

Larry Godwin

The Blue Crush program generates weekly crime reports that identify hot spots — zones of heavy criminal activity within a precinct — to MPD, which then focuses resources on where police are most needed. Police inspectors — the rank of most precinct commanders — can decide the day, time, and tactics to launch a Blue Crush operation on a hot spot. Patrolmen credit Blue Crush with getting the proper number of officers on the street during operations.

Blue Crush also supplies MPD with the finances necessary to keep extra manpower in the hot spots. Officers work Blue Crush operations on their days off and earn overtime without costing the city. “Because we are the university, we have access to grants. Part of our job is to push the edges,” Janikowski explains.

The hot-spot approach feeds off of criminal psychology, which, as Janikowski explains, is not unlike regular human behavior.

“We tend to go to work the same way every day, go to the places we know and are comfortable in,” Janikowski says. “Offenders are the same way. They’ll offend in the neighborhood they’re used to.”

Janikowski has taken the geographic approach to reducing crime in Memphis due in part to some of the city’s unique historical and demographic features.

Urban renewal and the abandonment and reclamation of downtown in the past half-century have shaken up the city’s residential and criminal patterns. “As public housing closed down, we dispersed people,” Janikowski explains. “Offenders became more mobile than they used to be, and crime has expanded into areas that weren’t necessarily targeted before.”

While the idea that Memphis crime is expanding its horizons may not reassure residents, Janikowski insists that the situation aids crime-fighters. “The advantage to having offenders operating where they aren’t comfortable is that that’s when they make mistakes and get caught,” he says. “A group started doing robberies in Collierville. They robbed a woman in her driveway. Collierville PD got them because those fools got themselves lost in the subdivision.”

Susan Lowe

Susan Lowe

On the scene: an MPD officer at work fighting crime.

Every Thursday morning, high-ranking officers from each of the city’s police precincts gather at Airways Station to discuss the results of the previous week’s Blue Crush operations and announce plans for the next.

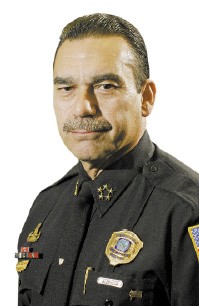

Director of Police Services Larry Godwin and 20 lieutenants, majors, and inspectors from across the city sit at a horseshoe-shaped table that faces a screen and podium. The scene recalls DC Comics’ Justice League of America, albeit with more guns and less colorful costumes. Another 50 police personnel sit at rows of tables to observe. One officer likens it to a scene from the TV series The District.

Janikowski welcomes a couple of guests to the meeting, pointing out that they can help themselves to a cup of coffee “and — of course — there are donuts.”

Godwin kicks off the meeting with a general address. He’s nothing if not concerned with the public perception of his officers. After receiving complaints about cops talking on cell phones while on duty, he urges greater discretion. “I could pull up beside an officer on the phone [in his car] and put a bullet in the back of his head, and he’d never know it,” he told those gathered at the meeting.

After Godwin’s address, those in the horseshoe take turns giving PowerPoint presentations from the podium detailing statistical breakdowns of particular crimes in their respective precincts. They flash graphs and tables on the screen. They compare the given week to the three leading up to it, as well as the same week in the previous year. If certain tactics fail to suppress a problem in a hot spot, they try something else. “Precinct commanders have to decide where police will operate in their precincts based on the [Blue Crush] data packages they receive. They know their area. They’ve got to decide how to best use their resources,” Janikowski says.

Crime does go down in the hot spots. The question remains whether or not Blue Crush reduces crime across the board.

Through these snapshots of weekly Part I crimes in the city, one learns that residential burglaries occur in nearly epidemic proportions. If “epidemic” seems too strong a word, ask yourself if 82 new cases of avian flu in a month in Hickory Hill would alarm you. Residential burglaries outnumber every other crime in virtually every precinct in the city.

Blue Crush in action deploys combinations of visible patrolmen to suppress criminal activity and plainclothes officers to gather intelligence on the street. Though officers are generally pleased with the extra manpower that Blue Crush operations mobilize, some wonder if full-time undercover officers could enhance results.

A white officer joked that he and his partner going plainclothes had little to no effect in their predominantly black precinct. He mocked the idea of two whites driving around asking groups of young blacks, “Got any dope?”

Street cops have other concerns. Some say that attrition in their numbers from retirement and relocation outpaces the number of new recruits. One officer said that he counted only 40 graduates from the MPD training academy since Mayor Willie Herenton’s call for an expanded force last fall. (The idea of a new publicly funded football stadium is unpopular among those who have not received a pay raise in two years.)

Janikowski explains that increased efficiency and proper usage of resources could address some of the force’s manpower issues. “Blue Crush is reengineering the entire police department and restructuring things,” he says.

“The TAC unit [the Memphis equivalent of a SWAT team] does barricade and hostage situations and dignitary protection. The rest of the time, they’re working out and shooting, and they look really tough while they’re waiting to get called out. They’re the best trained, in the best shape. Give them warrants each day to go and chase some folks. This has been happening over the last six months,” Janikowski explains.

While the issue behind much of the city’s crime is easily identifiable, it remains difficult to solve. “If I was going to pinpoint a particular problem, it would be gangs, because it relates guns, drugs, robberies, and burglaries,” Godwin says.

Janikowski adds that predominantly African-American gangs drive crime statistics disproportionately. “The gangs are making their money in the drug market, in guns, and in stolen goods,” he says.

Godwin notes some incremental progress: “About eight months ago, we locked up 55 known gang members. That doesn’t sound like a lot when you’ve got 5,000 gang members [in the city]. But when you’re hitting the upper echelon in those gangs, it puts them in turmoil.”

Janikowski, however, says that Memphis gangs are highly fluid institutions with high turnover rates and no hierarchy. “They’re not these solid, corporate structures like the Mafia. Even gang allegiance changes. Some guys have tattoos from the Gangster Disciples and Vice Lords,” he says, adding that they show resilience to arrests, deaths, and defections from within the organizations. “They’re like any other employer. When they lose an employee, they hire another one,” he says.

Gangs’ modi operandi feed the police strategy for fighting organized crime. “We embed undercover officers in the gangs,” Godwin says. “I’m a firm believer in the undercover program in the gangs. I don’t think going around in a car that has ‘gang unit’ written on it is going to get you into the gangs and get you those good arrests. You’ve got to be one of them. You have to buy the guns, buy the drugs, and watch them deal in prostitution. Then build cases that way and make them stick.”

“Good arrests” for the police are federal crimes, since state-level convictions seldom result in more than half of a sentence served.

“We get a lot of information from being embedded [in gangs]. We’re living with them. It’s like any other rumor mill. You hear things within the gangs. We start to try to verify those things and substantiate whether or not it’s a possibility that a hit is coming down here,” he says, adding: “I’m all for reaching out to gangs and saying, ‘One of your members was shot. Let the police handle this instead of retaliating.’ I wish we could reach out more and make that arrest before the other gang can retaliate.”

Which brings us back to unlucky 34. The proverbial word on the street says that an organized crime outfit wanted Mario McNeil dead. McNeil was, by various accounts, a devoted father, a small-business owner, and a singer in his church’s choir. Those mourning McNeil’s murder left 15 pages of remembrances on his online obituary guestbook.

Whether McNeil’s murder was the result of gang activity or a random act of violence against an innocent, his story is symptomatic of an old problem that could prove immune to new cures.

“There’s no magic bullet. I think that is something that the media tries to feed [people]. ‘If we had this, it would solve it,'” Janikowski says.

No one disputes the prevalence of black-on-black violence in Memphis. The numbers don’t lie. MPD strategy, however, is, technically speaking, color-blind.

“We don’t address [black violence] in any way different from any other crime. We look at areas. Some of those may be predominantly African-American [parts of the city], but we address them all the same. A crime is a crime to us,” Janikowski says.

The future of crime-fighting might also be impacted by this year’s Memphis mayoral election. Though Herenton stands firmly beside Godwin, mayoral candidate Carol Chumney promises to devote fresh energy to the issue of crime. Though Janikowksi favors the long view of crime statistics and advocates patience with the progress of any crime remedy, Chumney says that Blue Crush should be scrapped if it isn’t working.

“Nothing’s immune to politics,” Janikowski says. “As it becomes ingrained in the police department, as the public sees effects over time, it’s going to be the way we do business in the future. It may not be called Blue Crush, but this idea of data-driven policing is here to stay.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Susan Lowe

Susan Lowe