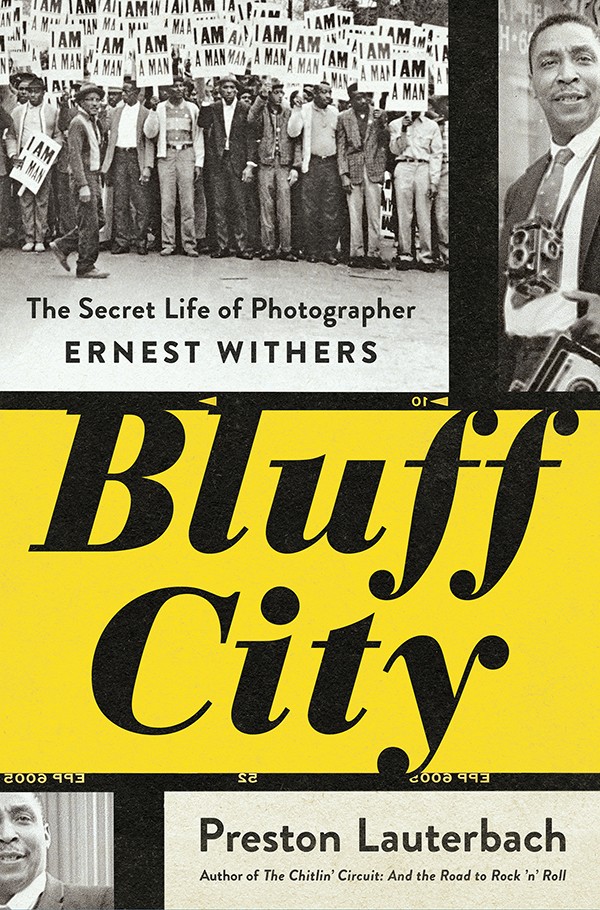

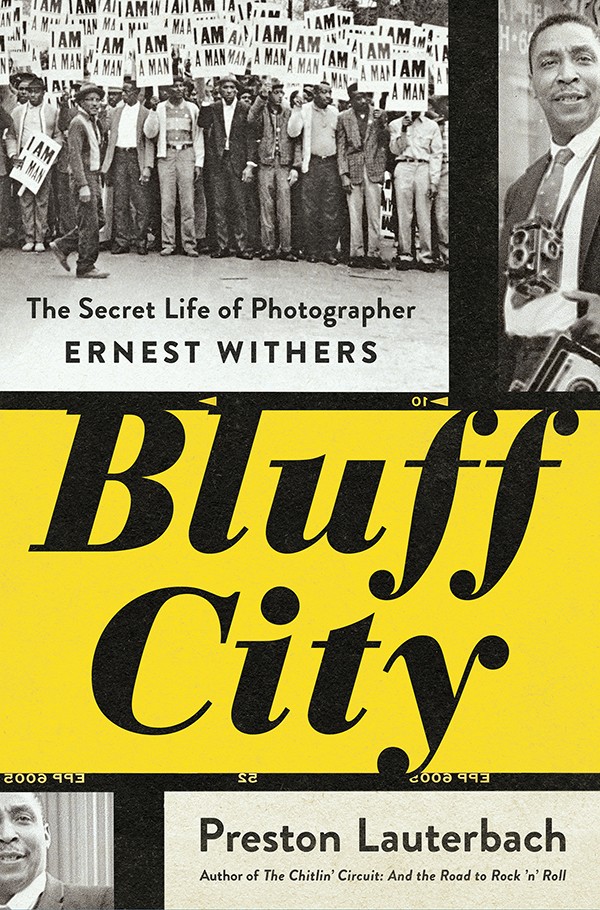

Last week, as Ken Burns visited Memphis to unveil his upcoming series, Country Music, he said he considers himself not so much a historian as a storyteller. It’s a distinction salient to Preston Lauterbach’s new book, Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers (Norton). As was seen in reportage by Marc Perrusquia nearly a decade ago, and in his subsequent book on Withers from last year, the subtle differences between history, storytelling, and journalism make a dramatic impact on the final framing of a narrative.

Perrusquia’s work, for example, was centered on the writer’s own sleuthing, and his ultimate triumph in gaining access to the FBI’s file on Ernest Withers. The reporter’s success turned Withers’ life story into one big “gotcha” moment. Revelations that the renowned chronicler of the civil rights movement had made regular reports on that movement to the FBI’s Memphis field office were indeed earthshaking, but that narrative of betrayal so overshadowed any other perspective on Withers’ life that many Memphians who knew Withers resented Perrusquia’s detective work.

Lauterbach’s storytelling offers a refreshing widening of perspective. His more holistic focus on Withers’ life, in all its contradictions, makes that life emblematic of Memphis history itself. And it’s undeniable that the photographer, a lifelong Memphian, embodies the city’s distinct character, not least in his willingness to think outside the box and forge his own independent path.

Elise Lauterbach

Elise Lauterbach

Preston Lauterbach

Lauterbach’s previous volume on Memphis history, Beale Street Dynasty, was loosely organized around the life of African-American millionaire Robert Church, with the city itself a character in the tale. Because that book did not aspire to biography, even in its title, the wide-ranging digressions on other major players in the Beale Street saga made narrative sense.

The new work, then, is a sequel to that tale, bringing Beale Street into the late 20th century. Withers was a fixture there, setting up his studio “in the thick of the midnight world.” There, Withers gained easy access to clubs on the street, snapping photos of patrons and performers alike, then running across the street to develop and sell them that same night.

This, along with with Negro Baseball League players and everyday weddings and funerals, became Withers’ initial subject matter. And he is defined in this book primarily by the places he went and the things he did. As a biography, it makes little headway in unpacking the psychology of its subject, or his relation to his friends and family. The Ernest Withers of Bluff City is primarily a doer, with an instinct for finding significant events and the flash-frame moments that express them.

Lauterbach has a storyteller’s gift for setting a scene — and the threads leading to moments captured by Withers’ lens. A digression seemingly unrelated to Withers’ life or personal relationships will culminate in the moment immortalized by Withers with a single, well-chosen shot. And as the civil rights movement heats up, becoming more torn by its internal factions, the scene-setting comes to dominate the tale, as extended digressions on the lives of key civil rights figures cause Withers’ personal story to vanish at times.

One salutary effect of this is a more informed perspective on Withers’ relationship with the FBI. When Withers first begins reporting on civil rights groups’ activities, it’s clearly a natural extension of his reliance on federal authorities to keep him safe from more racially blinkered local police, as when FBI agents investigate his abuse at the hands of officers in Jackson, Mississippi.

As the movement develops, the ethics of Withers’ involvement become more blurred. If, on the one hand, his reporting on the Nation of Islam helps counter the FBI’s tendency to paint them as instigators of violence, he’s equally willing to buy into the Bureau’s anti-Communist rhetoric, brazenly misleading Northern activists to earn his informant’s wages. In light of Richard Wright’s disillusionment with doctrinaire Communists in Black Boy, it’s understandable, but Lauterbach never really digs into the historical complexities of the Left’s racial politics. For that, one must turn to other sources. The implication — that Withers was trying to insulate moderate activists he deemed legitimate from accusations of extremism — remains merely an implication. Teasing out such ethical and political niceties is precisely where the book’s storytelling falls short of historical analysis.

Of course, Withers’ true intentions will always be mysterious. Having passed away in 2007, he’s never been able to answer accusations of “spying” directly. But Lauterbach’s tale, with its greater sensitivity to the contradictions inherent in surviving racism, goes a long way toward a fuller, more human vision of a life lived in the fray.

Elise Lauterbach

Elise Lauterbach