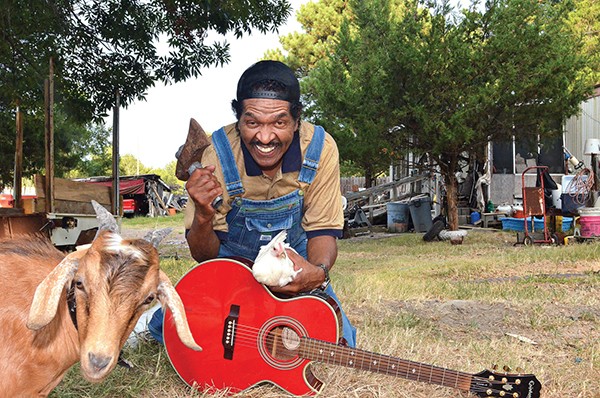

Despite having won a Grammy award a few years ago for his album Porcupine Meat, and several Blues Music Awards to boot, you can always rely on Bobby Rush to keep things down to earth. That’s obvious enough on the cover of his newest album, Rawer Than Raw (Deep Rush/Thirty Tigers), released last week, which features him chasing chickens in a farmyard.

That image is in perfect keeping with the album’s sound, and, like the recordings themselves, was only chosen for the album after the fact. “This wasn’t planned to be no album cover. It was something I’d done because I wanted to go back to my roots. An old friend that I knew, in his backyard. That’s where I was raised up. Every day, my mama would say, ‘Boy, we need a chicken to eat.’ And we’re out in the yard, we kill a chicken. That’s the way we did it!”

Kim Welsh

Kim Welsh

Bobby Rush

And that’s just how he recorded this album, accompanying himself on guitar and harmonica, his foot stomping the beat. While its closest precursor, 2006’s Raw, was similarly stripped down, it did feature a dobro player on some tracks. This one is different.

“Ain’t nobody there but me, mane! Nobody. I had a harmonica around my neck. And when I got to someplace where I’m singing, I went back and did a couple lines with the harmonica, but that’s the only overdub. If I messed up, it’s messed up. If I got it right, it’s right. It’s one take down! I got a board at my feet, and me patting with a damn board, man. Feet going one way, as a drum, and my thumb going one way as a bass player, and the fingers going one way as a guitar player. Doo-rwee-dap-dap, doo-rwee-dap-dap, bop bop!”

Like the cover image, the tracks weren’t made with an album in mind. He may well have been recording with his touring band now, but COVID-19 got in the way. Rush is convinced that the coronavirus was the illness that beset him in February and March. He’s grateful that he pulled through without any long-term effects but wants the world to know how serious the situation is. “It’s no joke. Wash your hands, keep your mask on, and try to stay to yourself as much as you possibly can. I know you wanna hug and kiss and touch, but that’s a no-no right now.

“I didn’t record this while I was sick. I had already done these things. I wanted to do something, and I thought, ‘What am I gonna do?’ You can’t go out. So I said, ‘Dog! I’ve got at least 150 songs already recorded.’ I picked out some that I started with my guitar, and I said, ‘Hell, these are already finished!'”

Choosing which of those would make a coherent album was another matter. “I said, well, let me try to salute all the people that I love and respect. Still, I couldn’t put all of them on one CD. I said, ‘Let me pick the guys from Mississippi. Like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. People that I knew back in the day, that I respect highly.’ That’s one reason. The second reason is, the guys from Mississippi never change. When they’re Mississippi blues men, you know who in the hell he is. ‘That’s it. It’s from Mississippi.’ But I’m not doing it just like they would do it. I’m doing it my way.”

Beyond that, he’s mixed in five of his originals, including the opener, “Down in Mississippi,” and the inimitable “Garbage Man,” best summed up by the line, “Out of all the men my woman coulda left me for, she left me for this garbage man. … Every time I see a garbage can, I think about her and the garbage man, all the time!”

It’s especially stark, featuring only Rush’s wailing harmonica, voice, and stomping foot. Rawer than raw, indeed.

Though he’s best known for his crack band on the touring circuit, he’s lost none of the chops he refined when he had no ensemble to rely on. “When things go wrong, I take it out on my guitar. And I sing about it and soothe myself.” The album’s climb up the charts suggests that listeners can relate. “Maybe they like it,” he surmises, “because it represents being alone by yourself, set aside, with nothing to do.”