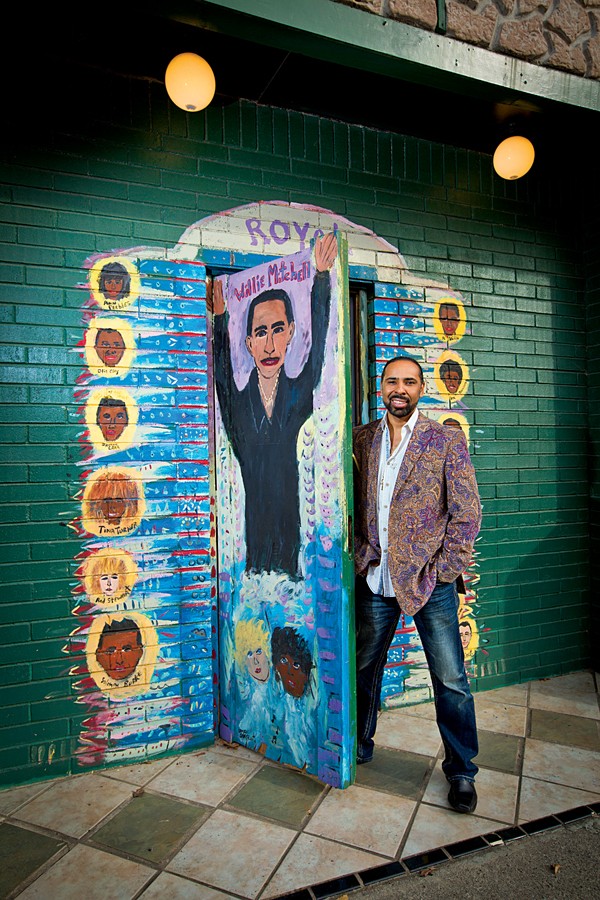

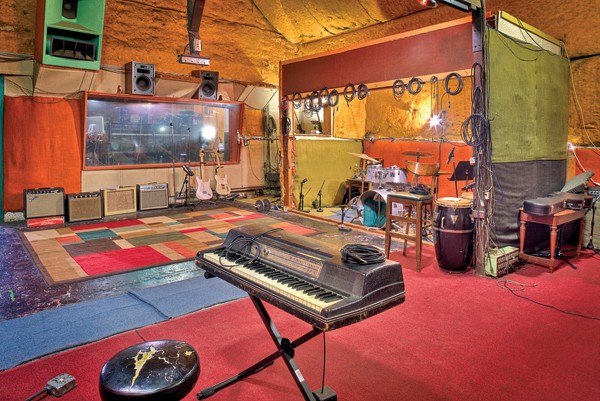

Jocelyn “Jozzy” Donald is recalling her mother’s glory days in the recording industry. “She was a singer with Hi Records, with Willie Mitchell producing. She had a group called Janet and the Jays, back in the day. Boo Mitchell knows my whole family.”

It’s the kind of memory a family can treasure, a brush with greatness, a bit of immortality on vinyl. The group not only worked with a producer who became legendary, they recorded songs by writers like Don Bryant and William Bell, masters of their craft. They too have become legendary, though Janet and the Jays fans would only have seen their names in the very small print below the songs’ titles. That’s just how songwriters were credited. In the age of streaming, the people who composed the music are often completely unacknowledged (though the Sound Credit platform designed by Memphis’ own Soundways is trying to change that).

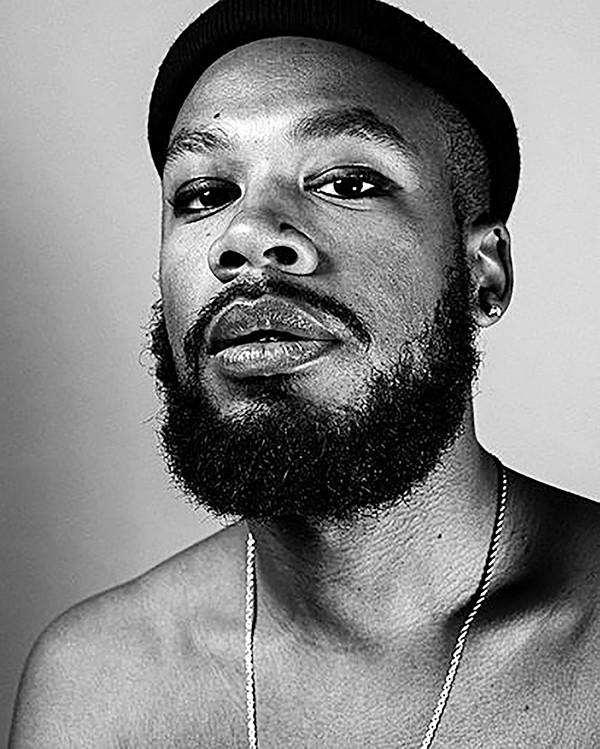

Chris Paul Thompson

Chris Paul Thompson

Jocelyn “Jozzy” Donald

The lack of public credit given songwriters is all too apparent when I ask Boo Mitchell if he remembers Jozzy and her family. “Sure!” he says. “She writes music herself. I recorded some of her first stuff in the four-track room at Royal Studios.” It’s yet another moment in the big small town of Memphis, where everyone seems to know everyone else. But he’s not ready when I toss out another factoid: that a song she co-wrote is currently the No. 1 song in the nation — a little number called “Old Town Road.”

Matt White

Matt White

Don Bryant

“Really?” he exclaims. “Good for her!”

It’s a Memphis thing. Great songwriters are crawling out of the woodwork, and most of us don’t even realize it.

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

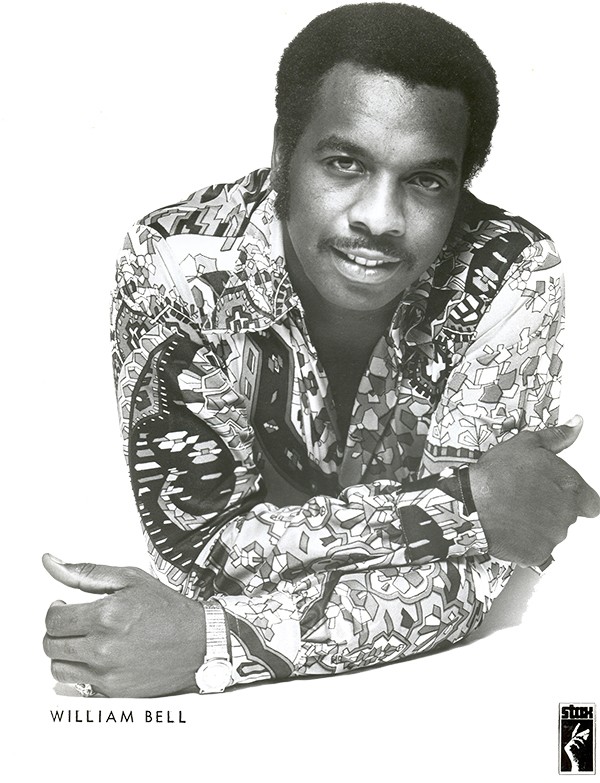

William Bell

In the case of Jozzy, it’s a tale many years in the making. “My brother became a recording artist but got locked up. So I pretty much took his whole love of music and just ran with it. That’s what happened with me falling in love with music. I started working at this studio called Traphouse, with DJ Larry Live. He’s actually Yo Gotti’s right-hand man now. He had a studio on Highland, right near the University of Memphis, and I used to go over there and write. That was where I got my start. I was still at Germantown High School then. All the rappers in the city knew me as the girl who wrote hooks. I was just the hook girl.”

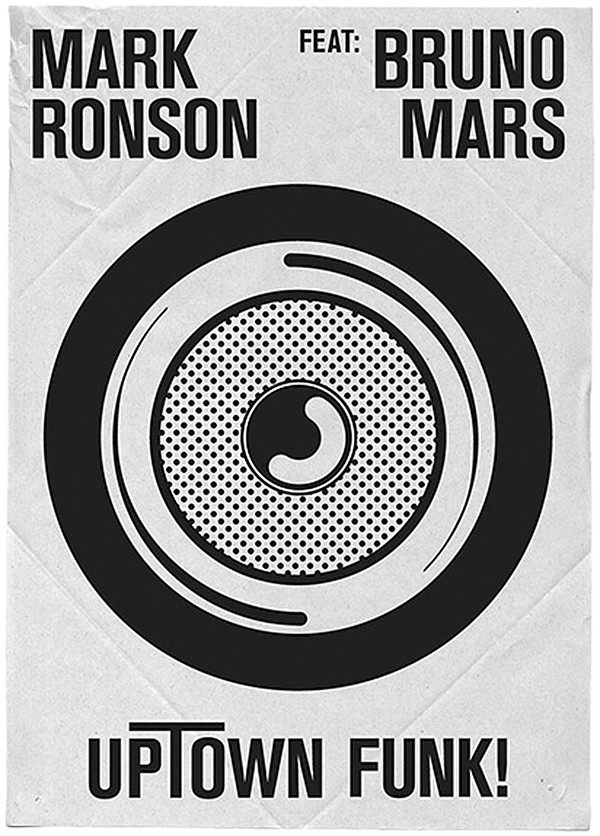

Word of her prolific creativity got around, and before long she was working with famed producer Timbaland in Miami. Then came a move to Los Angeles and being signed to Columbia Records as an artist in her own right. It was then that her label mate, Lil Nas X, found he needed a hand supplementing a song he’d already written and released.

“Old Town Road,” his song of determination in the face of alienation, made use of the old pop trope of the African-American cowboy, which dates at least as far back as the Coasters or Jamaican dub legends the Upsetters. But having a banjo-driven track with Western themes wasn’t enough for the Nashville establishment to recognize the song as a legitimate entry on the country charts. So Lil Nas X upped the ante and actually featured a country star in a remix of the song. That’s where Jozzy came in to write an extra verse for the cameo.

“I just love that Billy Ray Cyrus really stood behind us,” says Jozzy of the star she ended up writing a passage for in the remix. “Because Billy Ray went through the same thing with ‘Achy Breaky Heart,’ which they also took off the country charts. So he could relate to it. And really, the controversy added to the greatness of the song, but I hate that the country music industry had to act like that. Still, new country artists like Keith Urban are supporting this song.”

Indeed, country fans even love it. When Cyrus brought Lil Nas X out for the song at the recent Country Music Association Music Festival, the crowd went crazy.

Now dropping her debut single as an artist, “Sucka Free,” featuring Lil Wayne, Jozzy is poised for something most songwriters never receive: public acclaim. It’s almost a tradition in Memphis, which does not always get the same credit as Nashville as a font of song creation. The absurdity of that is apparent if one simply reflects on the songwriting legacy of the Bluff City. Of course, Memphis looms large in the Songwriters Hall of Fame, where notable inductees include Al Green, Isaac Hayes, David Porter, Otis Redding, Maurice White, and W.C. Handy. Keith Sykes, now managing Ardent Recording Studios after a lifetime of songwriting for himself and other artists like Jimmy Buffett, recently attended this year’s induction ceremony for the New York-based institution and saw fellow Memphian Justin Timberlake receive the Contemporary Icon Award. “He also closed the show. Fantastic, man! And he gave a huge shout-out to Memphis, several times,” Sykes says. His friend and erstwhile collaborator John Prine, who is rightfully honored as the gold standard of songwriters, also was inducted, causing Sykes to ponder Prine’s longtime connection with Memphis.

Keith Sykes

“He did his first album here, with Don Nix at American,” recalls Sykes. “He did Common Sense here and Pink Cadillac here. He’s done a bunch of stuff in Memphis. And he loves it down here.” Beyond working in the city so often, Prine has influenced a whole crop of songwriters based here, who took his template of finely honed, detail-rich narratives to heart. The great John Kilzer, whose recent death is still being mourned, was one such practitioner of the narrative songwriter’s craft. “John Kilzer, I signed in 1986,” says Sykes. “His songs, you could just tell there was something there.”

Beyond his natural talents of observation, Kilzer studied creative writing at then-Memphis State University. It’s a path that other songwriting greats have taken as well, including local writer and performer Cory Branan, whose tightly woven tales are gems of song construction. (I should know; I sometimes play bass for the guy.) English hitmaker Frank Turner recently quipped, “The thing about Cory for me is, almost every songwriter I know is slightly embarrassed by his existence, in the sense that he’s just better than all of us. And should be more successful than any of us.”

Cory Branan

Branan says studying creative writing and literature can indeed enhance this approach to songwriting. “I didn’t write songs until I was 24 or so, but I wouldn’t be doing this if I hadn’t tested into the right classes when I was in school in Mississippi. My teacher, Ms. Evelyn Simms, went off the curriculum, let’s just say that. She would see what we were interested in and then steer us toward things that technically she couldn’t assign.”

From wider reading, Branan learned to take in the wider world. “Keats called it ‘negative capability.’ The idea of not having a persona or a personality, to be able to pursue another one. Basically, not getting your fingerprints all over shit.” (Playing with him and seeing rooms full of fans singing along to “The Prettiest Waitress in Memphis” and others attests to the power of evoking characters that may or may not reflect the songwriter himself.)

It’s an approach that befits almost any style of songwriting, revealing a basic attitude toward the craft that transcends any genre or timely trends. Producer IMAKEMADBEATS, reflecting on songs he’s cowritten with singer Cameron Bethany, puts it this way: “The thing about stepping out of the world of hip-hop, whether it’s for a Cameron Bethany record or an Aaron James record, is that you get to just shamelessly become somebody else. You get to really take on the perspectives of another person. And try to tell that story. With that, songwriting is fun to me because it becomes infinite. I’ve heard songs by people from the perspective of being a gun. I’ve heard songs from the perspecitve of what they thought it was like to be their parents. You can take on any and all perspectives.” Memphis native William Bell, one of the first hitmakers for Stax Records and a 2017 Grammy winner, would agree. “I started singing with the Phineas Newborn Orchestra when I was 14, and I was always a people watcher. At that age, I couldn’t go out in the club, so I had to sit backstage and peek out at the audience. And I would just watch people as they’d come into the club, and after a couple drinks, how they were acting. All of that stuff just kinda hit home, and I wrote about a lot of that just from observation.”

Catherine Elizabeth

Catherine Elizabeth

Cameron Bethony

Don Bryant, who started in the same era and for a time put off his own performing career to become a staff writer for Hi Records (penning “I Can’t Stand the Rain” for wife Ann Peebles), is similarly inspired by the everyday tales he hears around him to this day. “I had six brothers,” Bryant recalls, “and they always came home with something, or I’d be out in the neighborhood and you hear little things. After a period of time, you visit back on those days and you see a whole lot of things. I pull stories from anywhere I can.”

While much younger than pioneers like Bell or Bryant, Greg Cartwright is universally admired in Memphis as a writer whose songs might have been written in their heyday. As such, his recorded work (on which I’ve played in the past) stands as a kind of bridge between the classic songwriting that emerged from studios like Stax, Royal, or American and the edgier, punk-infused style of bands like the Oblivians or the Reigning Sound.

Kyel Dean Reinford

Kyel Dean Reinford

Greg Cartwright

“I write about things that I’m familiar with,” he says, “so I can speak with authenticity when I say it. But that doesn’t mean necessarily that it happened to me. It just means that I can empathize with the idea. Even though it may not be purely autobiographical, it’s certainly something that I can understand and empathize with. I’m not saying it’s about me so much as to say, ‘I empathize with you if you feel this.'”

But if not autobiographical, Cartwright feels it’s imperative to find one’s authentic voice, something he did through a longtime bandmate. “When I met Jack [Oblivian], he was the first person I met who didn’t sound like anybody I’d ever heard. He wasn’t trying to sound like anybody I could put my finger on. Sure, he had lots of influences, and he would tell you right away what they were, but in my early 20s, most people were very taken with whatever the music of the time was or whatever their social scene was into. And he just seemed like he was just flying his own flag.” In the end, this willingness to buck prevailing trends and pursue a personal vision may be the hallmark of all the city’s great songwriters. “What I look for is something fresh and original,” says Sykes. “And I can never put my finger on what that is.” Some toil at length to build that quality into their songs. “I work hard at making things sound off the cuff,” Branan told one interviewer. Others, like Jo’zzy, take another route. “Your first mind is everything,” she says. “Your first melody that comes into your head, normally that’s the right melody. I tell my manager all the time, ‘Never play me a beat before I go in the studio.’ I’d much rather go freestyle.”

Yet another approach to forging individuality is to be overwhelmingly prolific. Kirby Dockery, a graduate of the Stax Music Academy, left Berklee College of Music to pursue her music career, but was having trouble getting recognition. Her resolve led her to post a song a day on YouTube — eventually culminating in 200 compositions and being signed to Jay-Z’s Roc Nation Publishing. There, she ascended to what is surely the songwriter’s mountaintop, co-writing “Only One” with Kanye West and Paul McCartney, and “FourFiveSeconds” with West, McCartney, and Rihanna.

Josiah Roberto

Josiah Roberto

Kirby

Working under the name Kirby, she reflects on the role of the Stax legacy in her achievements. “The Stax Music Academy [SMA] was one of the first catalysts that helped me believe that songwriting wasn’t just a dream. It was there where I first heard my lyrics and melodies put to music. If it wasn’t for SMA I wouldn’t have had the pleasure of meeting my future publisher years before I even knew how to be signed as a songwriter. SMA planted seeds that are still blooming in my life today. I am forever grateful.”

To that end, she’s now giving back to the institution. As SMA executive director Pat Mitchell-Worley notes, “Kirby offered four scholarships to students in the program, based on the students creating original material. And she listened to every song that was offered. And not only did she pick the best ones, she gave them feedback on their songs. So her scholarship reinforced our songwriting focus.” In fact, the SMA is now promoting the importance of songwriting more than ever.

“For the upcoming regular school year,” says Mitchell-Worley, “we have a full songwriting track. Songwriting and music business. And the two go hand in hand. If you’re gonna pursue a career as an artist, you need to have every form of revenue that you can grasp, and songwriting is a very important part of how you get paid. Students have come to understand more that owning the material that they record and perform affects their revenue streams.” Beyond that, they’re thriving on the creativity that such an emphasis fosters.

Perhaps an old tune by Youmans, Rose, and Eliscu from 1929 puts it best, reeling off the reasons we should be grateful for the craft that has shaped the city’s history for so long:

Without a song, the day would never end

Without a song, the road would never bend

When things go wrong, a man ain’t got a friend …Without a song.

Eric Allen

Eric Allen

David McClister

David McClister  Ronnie Booze

Ronnie Booze  Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon