A Woman in Charge

By Carl Bernstein

Knopf, 628 pp., $27.95

Her Way

By Jeff Gerth and Don Van Natta Jr.

Little, Brown, 438 pp., $29.99

Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, the TV prime-time soap opera that flared for several seasons in the 1970s, focusing largely on the marital disappointments of a loyal but necessarily self-reliant wife, had nothing on the Hillary Rodham Clinton saga of our own time. Two new biographies of the latest Clinton to have a go at the presidency of the United States offer revealing insights — and some gossipy asides — about the life of the former first lady and current U.S. senator and presidential hopeful.

Hillary, Hillary, the combined saga might be called. Not that other book-length treatments aren’t out there, but most of those are either authorized hagiographies or hothouse-cooked hit pieces. Carl Bernstein’s A Woman in Charge does full justice to its subject, and, to a somewhat lesser degree, so does Her Way, by sometime New York Times-men Jeff Gerth (the investigative reporter who virtually invented the ephemeral but fateful Whitewater scandal) and Don Van Natta Jr.

Both volumes make clear the signal importance of Hillary Clinton in the making of the president 1992 and 1996 and in the preservation of her husband’s tenure through the humiliations of the Monica Lewinsky affair that, hard as it may be to believe in this post-9/11 era, dominated the attention of the nation’s media for upward of a year.

Bernstein’s book is clearly the more sympathetic of the two treatments, though the erstwhile Watergate reporter does not eschew reporting on his subject’s all-too-visible warts. Not only was her mishandling of the ill-fated health-care legislation of 1994 a major factor in the Democrats’ electoral debacle of that year, Bernstein maintains that her slowness to comprehend Washington ways in earlier matters, like the over-ballyhooed Travelgate scandal got the Clinton administration off to an unnecessarily awkward start.

Interesting, too, is Bernstein’s estimate of Hillary Clinton’s intelligence as more methodical in a lawyerly way than her husband’s, which intimates of both Clintons regarded as essentially “off the charts,” if subject to the lapses in self-discipline characteristic of the “creative” temperament. But it was the “pragmatism” of Hillary Clinton’s mind, as well as her mastering of human relationships and capacity for adaptation, that enabled her husband’s political career to stay on track, flourish, and survive and that later allowed Senator Clinton herself to become a respected member of the famously clubbish U.S. Senate.

Bernstein deals in considerable detail with the “bimbo eruptions” that characterized her husband’s private life (and constantly threatened his public one), as well as with Hillary Clinton’s adjustment to them. Once again: pragmatism über alles. He also deals fully and sympathetically with the tragic denouement of her law partner and friend Vince Foster’s tenure as a White House aide.

Understandably, Gerth and Van Natta give the Whitewater matter a disproportionate share of attention. They also provide more insight into Hillary Clinton’s Senate career, however, devoting almost half their book to that phase of her life and suggesting that some of her most controversial decisions owed as much to her prior experience as first lady as to presidential-race considerations. They note her apologia for her 2002 vote to permit the Iraq war: “Perhaps my decision is influenced by my eight years of experience on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue in the White House, watching my husband deal with serious challenges to our nation.”

Although the two titles, A Woman in Charge and Her Way are not without occasional irony, both books ultimately portray a determined, ambitious woman with the strength and durability to confront “serious challenges” in her own right. — Jackson Baker

The Wrong Stuff

By Marcus Stern, Jerry Kammer, Dean Calbreath, and George E. Condon Jr.

Public Affairs, 326 pp., $25.95

How did Randy “Duke” Cunningham’s true nature remain concealed as he won election after election as a Republican congressman from California? How is it that such a doltish and despicable man wasn’t caught a long, long time ago?

Sure, he had the reputation of a hero and a patriot: the only American flying ace of the Vietnam conflict. But when he wasn’t burning up the skies over Southeast Asia, Cunningham was an intolerable husband and father whose ego and sense of entitlement were rivaled only by his greed and moral flexibility. Even the scumbags he did business with didn’t seem to care much for Cunningham, who is currently cooling his heels in prison for selling military contracts to the highest bidder.

The Wrong Stuff is adapted from reporting by the Pulitzer Prize-winning team of Marcus Stern, Jerry Kammer, Dean Calbreath, and George E. Condon Jr., who broke Cunningham’s story in the national press. It contains plenty of sordid and unsavory details not found in the original articles and sheds a bright light into some of the darkest corners of the American political system.

Readers, for example, are introduced to Cunningham’s money-man Kyle “Dusty” Foggo in the Casablanca-like world of Central America during Reagan’s secret wars. It was in the hotel bars — just outside the war zone — where Foggo, surrounded by a colorful cast of spies, terrorists, and death-squad commandos, learned to get what he wanted by plying legislators with booze and buying them cheap, sometimes underage, hookers. Foggo was made for Cunningham and vice versa.

One metaphor — perfect beyond belief — stands out: A hot tub on the deck of The Duke-Stir, a yacht given to Cunningham in exchange for services, was filled with polluted water directly from the Potomac. It was so fetid only Duke (and perhaps a lady friend) would use it, even at parties for the crème de la corrupt. But even partying in a bubbling pool of sewage isn’t the most telling detail in these pages.

Cunningham loved to tell people that the Tom Cruise character in Top Gun was modeled after him. It wasn’t true, of course, but he told the story anyway. As Vietnam’s only ace, he was known to play the patriot card at every turn. It’s unlikely that the strategy would have worked so well had the electorate known about events that occurred on the night before he was awarded the Navy Cross, the highest honor the U.S. Navy can bestow. He told his commanding officer he wouldn’t accept the medal. He was “holding out” for the Congressional Medal of Honor because he “needed that money.” His C.O. explained that there wasn’t money to be had with the medal and that people don’t “hold out” for the honor. They die for it. — Chris Davis

Welcome to the Terrordome

By Dave Zirin

Haymarket Books, 258 pp., $16 (paper)

Full disclosure: I know Dave Zirin, author of Welcome to the Terrordome: The Pain, Politics, and Promise of Sports. Zirin and I were pretty close acquaintances when we both attended Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, in the mid-’90s. Zirin also worked with one of my college roommates organizing and agitating as a campus socialist.

So I wasn’t all that surprised to see Zirin emerge as something of a genre unto himself a few years ago as the country’s foremost (first? only?) politically oriented sports writer, first with his online column “Edge of Sports” (EdgeofSports.com) and then with a book, What’s My Name, Fool?: Sports and Resistance in the United States. Zirin — who also writes regularly for Slam and The Nation — focuses on sports as a social, cultural, and economic arena as much as a realm of entertainment or athletic competition.

This second collection takes its title from the 1989 Public Enemy anthem (PE mouthpiece Chuck D. penned the book’s foreword), but the reference is to the New Orleans Superdome, a publicly financed stadium where the New Orleans Saints play football and where 25,000 of the city’s poorest residents — people who could never have afforded a ticket to a Saints game — were herded in the days after Hurricane Katrina. In the following weeks, Zirin points out, many of these citizens were relocated to yet another publicly funded sports stadium, Houston’s Astrodome.

In his introduction, “The March of Domes,” Zirin asserts that turning these “$500 million welfare hotels for America’s billionaires” into homeless shelters made tragedy into farce. And he uses this moment as an apt symbol for what drives most of his work: a perceived corruption of sports by “corporate greed, commercialism, and military cheerleading” that Zirin suggests has turned the games, in large part, against the very people who play them or are fans of them.

Zirin’s topics span the gamut of the sports world: how the shifting demographics of Major League Baseball are rooted in the moral messiness of globalization and the Reagan-era destruction of urban social services; the complicated, evolving relationship between the NBA and hip-hop culture; the exploitation of sports by the political class.

Sports are often considered an apolitical, if not an outright conservative, segment of the cultural landscape, but Zirin reclaims sports from a progressive perspective. — Chris Herrington

Laurel Canyon: The Inside Story of Rock-and-Roll’s Legendary Neighborhood

By Michael Walker

Faber and Faber, 248 pp., $14 (paper)

In 1978, I moved from Virginia to Los Angeles with a boyfriend, a Volkswagen van, and a few personal treasures, including a cassette case with dozens of tapes. The trip across country was fueled by music, and at first we cranked up Gregg Allman and Al Green or maybe Marshall Tucker if it was getting late. But once we headed west on Interstate 40, folk rock moved into high rotation. We were going to the promise land, baby, and all we cared about was Joni and Jackson and their pals.

Over time, the boyfriend left me, and the LAPD confiscated my van for unpaid parking fines. But the case of cassette tapes I still have, thanks to my husband who rescued them recently from our yard-sale pile. “You can’t sell these,” he said with indignation. “This is a classic collection.”

If I had read Michael Walker’s Laurel Canyon before cleaning out my closets, I would have made that decision on my own. A journalist by trade, Walker has retold the serendipitous story of how a fragile canyon in the middle of Los Angeles spawned a new kind of music industry and an unprecedented string of landmark hits, thanks to the collection of musicians who lived there during the 1960s and ’70s.

Consider this: Crosby, Stills and Nash sang together for the first time in Mama Cass Elliot’s Laurel Canyon living room; Joni Mitchell wrote “Ladies of the Canyon” from her cottage on Lookout Mountain Avenue; Frank Zappa kept his canyon cabin until he died there in 1993. And then there was everyone else: the Byrds, the Animals, Jim Morrison, Dusty Springfield, John Mayall, Peter Tork, Keith Richards, and, yes, Justin Timberlake, who lives there today.

Looking back is always risky, especially when the topic is counterculture and the target is baby boomers. But Walker’s work, rich in new research and anecdotes, never strays too far into nostalgia. And maybe that’s why his book, now in paperback, has spent almost a year on the Los Angeles Times bestseller list. A resident of Laurel Canyon himself, Michael Walker’s stories are told not with sentimentality but with a loving acknowledgement that time and place matter to us all. — Pamela Denney

Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President

John F. Kennedy

By Vincent Bugliosi

W.W. Norton, 1,612 pp., $49.95

What’s not to like about Vincent Bugliosi? Starting with Helter Skelter, his 1974 chronicle of the infamous murders by the Manson Family — whose members he successfully prosecuted — Bugliosi has seemingly set out to be the final word on the central legal cases of our time.

Stress on the word “final.” In each case, beginning with his tome on the Manson matter, which already had been evocatively handled in 1972 by Fugg member Ed Sanders in The Family, Bugliosi’s books have cleared up the loose ends left by other writers and commentators.

He did so with an energetic philippic against the acquittal of O.J. Simpson, with a reasoned assault on the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore, and with detailed treatments of several intriguing but lesser-known cases.

Now Bugliosi, in a massive volume that is heavy enough to double as a workout tool, has set out to close the book, as it were, on the most shocking political event of the last century. Bugliosi not only analyzes every conceivable aspect of the case, refuting all known conspiracy theories in the process, he comes up with the most complete catalogue of details imaginable.

We learn, for example, what pharmaceutical means Lee Harvey Oswald’s Russian bride Marina availed herself of on her wedding night to convince her husband he was marrying a virgin. More importantly, we follow the tergiversations of the presumed assassin all the way from his first political stirrings to November 22, 1963, when, Bugliosi leaves little doubt, Oswald perched at a window on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository and discharged three fateful rounds from his mail-order Mannlicher carbine.

Care to read the transcripted exchanges between a lippy Oswald and his Dallas Police Department interrogators? The most exhaustive (one might even say numbingly complete) forensic and ballistic examinations ever put between covers? The truth, blade of grass by blade of grass, about what happened — and didn’t happen — on the grassy knoll? Those things, and everything else you can think of, are all here in Bugliosi’s 1,600-plus pages.

This is not the sort of book that one just sits down and reads cover to cover, of course — not unless your vacation stretches all summer and into the fall. It’s rather like an omnium gatherum of the Kennedy assassination materials, a sort of single-volume Brittanica on the controversy and an ex parte treatment of unparalleled completeness and intensity. Prosecutor Bugliosi tries and convicts Oswald as a lone assassin and, after weighing all the evidence, rejects all possible appeals. — Jackson Baker

On Chesil Beach

By Ian McEwan

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 198 pp., $22

On Chesil Beach is a novel of perspective. At the book’s opening, its two main characters, newlywed virgins Edward and Florence, sit at the dinner table in their honeymoon suite. The prospect of wedding-night sex is the elephant in the room but for different reasons for each of them.

Edward (a historian) fears “arriving too soon,” but mostly he longs for resolution to his and Florence’s torturous (to him), chaste courting.

Florence (a violinist) has her own burden, but it starkly contrasts with Edward’s: “Sex with Edward could not be the summation of her joy, but was the price she must pay for it.”

What Edward and Florence are caught up in is timeless: the lack of perspective of the young. Lack of perspective, though, is not a problem for McEwan. He switches points of view and time frames with elegance.

The title of the novel calls attention to the setting on the Dorset coast. But it indirectly underscores the age as well. The wedding night takes place in 1962, and McEwan continually refers back to the complexities of Edward and Florence’s generation, rebellious against their parents’ patriotism and horrified by the threat of the nuclear era but still tied to the social conventions and mores of the earlier age.

Edward and Florence cannot know that they were born a few years too soon, but McEwan does. As he writes: “This was still the era — it would end later in that famous decade — when to be young was a social encumbrance, a mark of irrelevance, a faintly embarrassing condition for which marriage was the beginning of a cure.” He frames the couple’s struggles, with each other and within themselves, in terms that are anachronistic to them but illuminating to today’s reader.

An artist with the English language, McEwan has the ability to paint a whole scene within the brevity of a sentence. For example: “How extraordinary it was, that a self-made spoonful, leaping clear of his body, should instantly free his mind to confront afresh Nelson’s decisiveness at Aboukir Bay.” Words such as these are worth cracking the spine of On Chesil Beach. — Greg Akers

Boomsday

By Christopher Buckley

Twelve, 318 pp., $24.99

When the “greatest generation” decided to get all sex-crazy and pop out millions of postwar babies, they had no idea the effect such a population surge would have on the country’s economic stability. After all, people didn’t typically live to age 85 in those days. But with the rising popularity of wheatgrass shakes, Lipitor, and colon cleanses, baby boomers are living well past retirement age. And the MySpace generation is paying out the ass for them in Social Security.

The solution? Voluntary suicide, according to Gen-X blogger Cassandra Devine, the lead protagonist in Christopher Buckley’s humorous political novel Boomsday.

When Devine posts a late-night rant calling on her generation to rise up against their elders by rioting at golf courses and retirement communities across the nation, to her surprise the suggestion hits home, and she’s soon made the face of Social Security reform. She also encourages a senator pal to sponsor a bill urging baby boomers to kill themselves by age 70. She calls it “voluntary transitioning.”

Of course, she doesn’t actually want people to commit suicide, but talk of radical measures brings media attention to an otherwise humdrum issue. Devine hopes such coverage will force changes in Social Security. However, when polling of the under-30 set reveals that the majority of young people take voluntary transitioning seriously, the president of the United States begrudgingly appoints a commission to look into the issue.

Buckley (author of Thank You for Smoking) manages to make an important, and often boring, political subject the topic of laugh-out-loud satire. Though a boomer himself, the author seems to have a decent grasp on the habits (Red Bull, Ritalin) and obsessions (blogging) of a younger generation.

Much like Devine’s voluntary-transitioning bill, Boomsday manages to raise a major “meta-issue” (to use Buckley’s word). Hopefully, the powers-that-be will figure out how to repair the current Social Security system before real-life boomers are forced to trade their golf clubs for burial plots. — Bianca Phillips

Rant: An Oral

Biography of

Buster Casey

By Chuck Palahniuk

Doubleday, 318 pp., $24.95

When I first opened Chuck Palahniuk’s latest novel, Rant, I was prepared to be a little disgusted. It’s why I read Palahniuk: to revel in the horrors, to watch as the lives of characters implode, and to wonder how the hell Palahniuk comes up with his spectacular twists. And in Rant I got all of that in droves. But I found something else buried in the tangle of Palahniuk’s eighth novel: something weirdly like hope.

The title character, Buster “Rant” Casey (from Middleton in the Middle of Nowhere) is a poison junkie who gets off on being bitten by spiders, snakes, and coyotes. With his animal-bite obsession and his teeth stained black from chewing highway tar, the kid is nothing short of ghastly.

The book opens with the premise that two things are true: Rant caused a rabies epidemic, and Rant died in a nationally broadcast, explosive car accident. While the first premise is true enough, the idea that Rant died the day of the accident is constantly questioned. And it’s that question that makes Rant so enjoyable.

Palahniuk interlaces the real with the unreal in his alternative timeline of the world today. Because Middleton is so crowded, it’s divided into night and day, literally. “Nighttimers” are segregated from “Daytimers,” but in an act that’s part rebellion, part leisure activity, and mostly adrenaline rush, many Nighttimers partake in “Party Crashing,” a kind of demolition derby to disrupt the flow of traffic. Rant joins in this sport as soon as he comes to the city, meeting friends and making enemies among the Party Crashers.

Rant’s story is told in the form of oral biography, mainly through the eyes of the Party Crashers and fellow inhabitants of Middleton. It’s the distinctive voices of Echo Lawrence, Shot Dunyun, Neddy Nelson, and Green Taylor Simms that especially give the reader the clearest idea of who Rant was and what became of him.

Because Rant’s body is never recovered at the scene of the accident, people assume that, like Elvis, Rant is still alive. A cult of personality builds up around him, everyone swearing that they contracted rabies right from Rant himself. This is key to one of the central themes of the book: If enough people believe a lie, it isn’t a lie anymore.

The mystery of where Rant’s body went is what gives Rant its hope. If he survived the accident, where did he go? No one saw him leave the car. His clothes were left at the scene. What if he never existed at all? What if reality isn’t so real after all? After all, if enough people believe it, it becomes true. Right?

— Cherie Heiberg

Falling Man

By Don DeLillo

Scribner, 256 pp., $26

Don DeLillo is both the unlikeliest chronicler of 9/11 and perhaps the best suited.

Praised and derided for his emotional detachment and intellectual engagement with his characters and their world (which happens to be our world too), the New York-born writer is fascinated by seismic shifts in mass perception. In the case of Falling Man, however, there are so many emotions attached to iconic 9/11 images that DeLillo’s usual detachment might seem at best merely unsympathetic and at worst crass.

On the other hand, perhaps that’s exactly what we need: an incisive author who can cut through volatile emotions and the resulting ideological schisms and show us what really happened. That’s a lot to ask of one writer and one book, and honestly, Falling Man doesn’t — can’t — live up to it. It’s flawed in its slow pacing, elusive characters, and plot contrivances, and yet, it remains potent and powerful.

The novel begins, like so many of DeLillo’s books, with an intense first chapter. In just a few pages full of punchy passages cordoned off uncomfortably by commas, DeLillo creates a world turning itself inside out and readies readers for a novel about the most culture-changing American event since John Kennedy’s assassination.

That first chapter follows Keith Neudecker, a typically cerebral DeLillo protagonist, out of the Towers and through the streets, “sealed in ash” and carrying a stranger’s briefcase. Unthinking, he goes directly to his estranged wife Lianne’s apartment. Theirs was a grim marriage that produced a son, Justin, along with much suspicion and grief, but Keith emerges from the soot a changed man. Falling Man investigates the nature of that change and its effect on his family.

Everything is subtly askew in Falling Man, from the characters’ perception of their world to the prose itself. The phrase “whatever that means” is repeated throughout the novel, not in dialogue but in DeLillo’s omniscient narrator’s voice: “Keith stopped shaving for a while, whatever that means. Everything seemed to mean something.” Those words, typically as innocuous as an “umm” or a “like,” simultaneously invite and disregard meaning, as if old assumptions no longer hold.

These literary tics are extensions of many of the same postmodern ideas that 9/11 was supposed to have squelched, and yet DeLillo seems to be inverting them even as he reintroduces them, so these absences of meaning never feel like cop-outs. It’s simply a means of gauging his characters’ changing world, as if to ask: Are their transformations real? Was ours? — Stephen Deusner

Mere

Anarchy

By Woody Allen

Random House, 160 pp., $21.95

Add Woody Allen to the long list of authors who have plumbed Yeats’ “Second Coming” for a book title with this, his first collection of short fiction since Side Effects in1980. Mere Anarchy reminds us that Woody Allen is the master of the absurd. To put it plainly: No writer is funnier.

Those who wonder why Allen’s films over the past, oh, decade or so have not been very humorous will marvel at how hilarious he is on paper. Fans of his movies may recognize a few lines of dialogue here and there, lines that didn’t work as well in the movies as they do on the page. These short stories pop and shimmer with his surrealistic wit, his similes out of left field, his goofball character names, and his flat-out funny, Marx Brothers-style … well, “anarchy” is the word for it.

Allen’s prose is sharp, intricate, and dense with gags and wordplay. Sometimes it takes a couple or three readings to get the wit of a sentence, to follow Allen’s jump-cut mind.

There are many gems to savor in this book, and it is tempting to fill a review with quotes from the book. Almost every page dances with his crackling sentences and crackerjack jokes. This slim collection will remind you, movie-wise, more of Sleeper than Curse of the Jade Scorpion.

But not every story works. “Surprise Rocks Disney Trial” is a funny premise — cartoon characters mingle with real-world stars in incongruous ways — but flags after you laugh at its one-note foundation. This is a minor quibble.

Overall, the collection is laugh-out-loud funny, in a way belonging solely to Allen. No one else — except perhaps the late, great Donald Barthelme — so successfully crafts a short story as a jokey admixture of Dada and Robert Benchley. Forget that Small Time Crooks made you wince. Read “Calisthenics, Poison Ivy, Final Cut” or The Maltese Falcon parody, “How Deadly Your Taste Buds, My Sweet,” and be reminded that Woody Allen is still the most intelligent funnyman of our time. — Corey Mesler

I Love You,

Beth Cooper

By Larry Doyle

Ecco, 272 pp., $19.95

It’s highly possible that the best, funniest time at the movies this summer might be found between the pages of Larry Doyle’s I Love You, Beth Cooper. Sure, it’s a book, but the coming-of-age tale of geeky Dennis Cooverman is pure cinematic, teen-sex zaniness. It’s as if Doyle took all of the best elements of S.E. Hinton’s movie adaptations and the work of John Hughes, Amy Heckerling, and Savage Steve Holland and tossed them into that crazy, lightning-activated lady-making super-computer from Hughes’ own Weird Science to create the perfect teen-sex comedy.

In case the filmic tropes aren’t obvious — from the impossibly nerdy protagonist to the cheerleader with a heart of gold to the one-dimensional jock bullies — Doyle cherry-picks some quotes from classic teen movies (from Gidget to Ghost World) to place between chapters. He even has one character, Rich Munsch, cite movies (along with directors and years) at appropriate times like a flamboyant, human IMDb search engine.

The entire book takes place on one night after high school graduation, a ceremony in which Cooverman used his speech to declare his love for the titular Cooper, admonish the snobs and antagonists, and even “out” his best friend, Rich.

Doyle wisely places the story in the modern day so that we can relate when Cooverman is embarrassed by his unhip iPod playlist or recoil when Cooper’s boyfriend, the villainous Kevin, a violent army guy fresh from Iraq, is hopped up on cocaine and various spirits.

Doyle is a funny man: He wrote for The Simpsons before that show jumped the three-eyed mutant fish, and this book, alternately poignant and ribald, deserves to be wrapped in a protective library-style jacket in case any beverage-sipping reader dowses it with an unexpected, comically overdone spit-take — the kind one sees in the movies.

— David Dunlap

Shoe Addicts

Anonymous

By Beth Harbison

St. Martin’s Press, 336 pp., $21.95

Within the realm of “chick lit,” there is a special category that might be called “shoe porn.” Granted, regular chick lit usually includes shoes as well as clothes, boys, martinis, and shopping. Shoe porn makes shoes a major plot point (a stiletto, natch) if not a supporting character.

The first — and most famous — example of shoe porn is the story of Cinderella and the fabulous glass slippers that won her the prince. A more recent example is In Her Shoes. The novel, about two sisters who have nothing in common except their shoe size, was made into a movie with Cameron Diaz, Toni Collette, and Shirley MacLaine.

Shoe Addicts Anonymous fits right into the sub-genre. In this tale, four Washington, D.C.-area women bond over their love of designer shoes. One is a debt-saddled shopaholic; another an agoraphobic phone-sex operator. The cast is rounded out by a young nanny and the glamorous wife of a controlling senator.

All of them are a little lost and dependent on more than arch support from their fancy footwear. But in a desperate attempt to satisfy her shoe fix, one of the women starts a shoe-swapping night, which results in the four’s strange friendship.

Start to finish — or heel to toe, as the case may be — Shoe Addicts Anonymous is an entertaining read, including a shoe support group that deals with bankruptcy, a gay “boyfriend,” and a blackmail plot.

As with much chick lit, Shoe Addicts Anonymous is not going to challenge its audience’s worldview. But if it’s fairly predictable, it’s predictable in a way that most readers will find comforting … like slipping on a pair of fuzzy slippers after a night out dancing in three-inch heels. — Mary Cashiola

Rewind, Replay, Repeat:

A Memoir of Obsessive-

Complusive Disorder

By Jeff Bell

Hazelden, 356 pp., $13.95 (paper)

When you left town last, did you check to make sure you’d turned off the stove? Probably. But how many times did you go back to make sure?

For most of us, some checking is normal and brings peace of mind. But for people with obsessive-compulsive disorder — and there are 2.2 million Americans who live with it — the checking leads to rituals they feel driven to perform, as revealed in Jeff Bell’s memoir Rewind, Replay, Repeat.

Bell’s natural propensity for questioning and checking for accuracy served him well as a journalist. He rose quickly through the ranks of radio and in less than 10 years became a news anchor with KCBS in San Francisco, where he still works. But his successful public life was a counterpoint to the dark torment of his private life.

Dogged by the voice he labeled “doubt,” Bell constantly second-guessed his perception of reality, retracing driving routes to make sure he hadn’t run over something or picking up broken glass or twigs from the street, all in an effort to relieve the anxiety and quiet the tapes that looped in his head suggesting his oversight might cause someone else harm.

In this richly detailed narrative, Bell describes the exhaustive ways in which his obsessions played out and the extent to which they slowly began to strangle him. Only his wife Samantha was privy to his anguish and admirably stood by him as he sought help, through cognitive therapy and medication, to manage his disorder.

What’s remarkable is that Bell managed to keep his “quirks” hidden from friends and colleagues. Even a fellow anchor, with whom he shared an announcer’s booth for five years, was stunned to learn of his secret.

Writing the book was cathartic, Bell said during a recent phone interview: “I owe so much to others with OCD who shared their stories. Had I not read The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Washing, I don’t know where I’d be.”

That book opened a window onto Bell’s world. Bell hopes his own story shines light into the shadows for others imprisoned by this stifling beast. — Jane Schneider

Wish You Weren’t Here! The Black

Cat Anthology of Travel Humor

Edited by Cecil Kuhne

Black Cat, 267 pp., $13 (paper)

For me, there was one horrible vacation: a nine-hour canoe trip in which my family missed a cut-off point on the Buffalo River. We spent the day eating melted granola bars and shouting at each other in the Arkansas heat, while our only ticket back to civilization scraped sand in shallow waters.

So I could relate to Wish You Weren’t Here!, a collection of travel horror stories told by unlucky adventurers and edited by Cecil Kuhne. Everyone who has experienced a less-than-stellar vacation will relate too.

My favorite story in the anthology is the opening one: “Would You Belize?” by Christopher Buckley, who takes the reader on a group tour of Mayan culture. Even with tales of torture, however, the author’s light-hearted writing makes the story a quick read. For instance, Buckley bird watches not in a picturesque setting but at a dump abundant with foul garbage and fowl droppings. Meanwhile, Beano-happy vegans — the “He-Vegan” and “She-Vegan” — continue their quest of global conversion.

In “French Revolutions,” Tim Moore — undoubtedly one of the healthiest authors in the collection — decides to follow the Tour de France. By doing so, he discovers Paris. Readers will enjoy the humorous yet uncomfortable scene in which Moore also discovers the silkiness of his newly sheared legs.

But the character who left the greatest impression on me has to be Little Bit: the miniature poodle with rain boots, sea-green cashmere sweater, personalized traveling bag, and extensive leash collection. “Little Bit and the America” by Ludwig Bemelmans tells the story of the pooch’s escape from captivity on a cruise. And though I can’t say I cared for a bratty girl named Barbara, the little poodle grew on me. After all, it takes a special dog to stay mute while hidden beneath a scarf all day.

In Wish You Weren’t Here!, Kuhne has gathered some of the most memorable (and undesirable) vacations of modern times. With trips rivaling National Lampoon’s Vacation, the book may have you thinking twice this summer before lugging out the suitcases.

— Rachel Stinson

Where’s Waldo?

It begins with a weekend flea-market visit, as influential underground comix author Kim Deitch and wife Pam add to their collections of old movie stills and films (for Kim) and stuffed-cat toys (for Pam). It ends after a jaunt through pre-World War I New Jersey, a South Pacific island, and Midgetville, populated entirely by “little people.” What happens in between is funny, ribald, and bizarre, and it almost convinces you that it could be true — if not for the walking, talking, conniving cat, Waldo. Drawn to perfection, Alias the Cat (Pantheon) is classic Kim Deitch.

— Greg Akers

Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe Strummer

By Chris Salewicz

Farrar Straus and Giroux, 640 pp., $30

Introducing: Everything you’ve ever want to know about Johnny Mellor — aka Woody Mellor, aka Joe Strummer (of the Clash) — who tragically passed away in 2002 due to an undiagnosed heart condition.

But talk about exhaustive biographies: Chris Salewicz’s Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe Strummer takes the cake. Most music biographies fall victim to too much pre-fame, pre-relevance, and youth coverage, and Redemption Song is no different. Occasionally in the opening pages, Salewicz does flash-forward and back through Strummer’s adolescence, the Clash era, and post-death accounts from friends and relatives. For the most part, though, Redemption Song follows in chronological order, and the highlights of the first 160 pages — some of it slow reading — are as follows:

Strummer’s older brother suffered from depression and committed suicide when Strummer was 18. This had a massive impact on Strummer’s life and creative drive, including Strummer’s pre-Clash concern, the 101’ers, a decent pub rock band that never released recordings while together. Salewicz also traces during this period the ongoing development of Strummer’s stoicism offstage and drama and high energy onstage, behavior that came to its fruition with the Clash.

Naturally, the Clash sections of Redemption Song beat out the book’s beginning and end in terms of readability. Most interesting is the fact that the band was created by an impresario, just like the Sex Pistols, who had Malcolm McLaren. The Clash was more or less masterminded by a lesser known but equally brilliant London scenester/hustler by the name of Bernard (“Bernie”) Rhodes. The political phrases pasted on Strummer’s Telecaster, for example? That was Rhodes successfully launching a trend that carries on to this day.

Salewicz’s writing is workmanlike, and he gets the job done. It also helps that the author was a good friend of Strummer’s. This intimacy benefits Redemption Song, peppering it with minute details that a less familiar biographer might not know.

After the Clash folded, Strummer busied himself with sporadic projects, including but not limited to soundtrack work for Sid and Nancy, co-writing much of the second Big Audio Dynamite (Mick Jones’ post-Clash project) album, and recording a 1989 solo album, Earthquake Weather which turned out to be a flop.

The closing portion of Redemption Song is given over to Strummer’s final three to four years with the Mescaleros, his handpicked band, which made a respectable impact by jumping all over the musical map: reggae, roots-rock, ska, and much cover material. It was with this group that Strummer reignited the spark that burned hot during his days with the Clash.

Clash fans are encouraged to check out Pat Gilbert’s Passion Is the Fashion: The Story of the Clash. For Strummer fanatics, see Redemption Song. — Andrew Earles

Candid Camera

In 1976, William Eggleston was the first artist granted a one-man show of color photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But earlier in the ’70s and back in Memphis, where Eggleston lived, he was redefining black-and-white portrait photography in a series that is only now being published — a series of lightning-quick shots made using a large-format camera and a strobe. The subjects were friends and acquaintances. The settings were Memphis nightclubs. And the book based on these portraits is 5 x 7 (Twin Palms). There’s some signature color shots here too, but it’s Eggleston’s super-sharp images in black and white that, thanks to Twin Palms, finally come into focus. — Leonard Gill

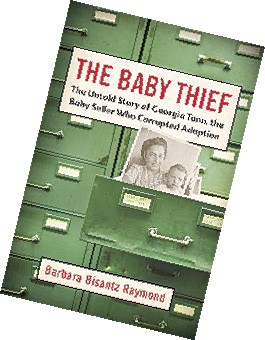

Baby love?

For more than three decades, Memphian Georgia Tann was praised for her hard-working efforts to place orphans with decent foster families. Would-be parents — including such luminaries as movie star Joan Crawford — came to the Tennessee Children’s Home and usually carried home a child. But the whole house of cards came tumbling down in the 1950s when investigators discovered that Tann was actually running an adoption-for-profit scam. Working closely with Juvenile Court, she took children away from their real parents and — for a fee — sold them to whoever put up the cash.

It’s not really an “untold” story, despite the title of

Barbara Bisantz Raymond’s The Baby Thief: The Untold

Story of Georgia Tann, the Baby Seller Who Corrupted

Adoption (Carroll & Graf). Mary Tyler Moore

played Tann in a made-for-TV movie some years

ago, and Memphis magazine covered the scandal

20 years ago. But it’s still a little-known one and

a cautionary tale that needs to be remembered.

— Michael Finger