The American West: land of manifest destiny. Troops fought for it. Farmers and ranchers settled it. Christopher “Kit” Carson was there too: as a trapper, a scout, an army leader, and a homesteader himself. He had unsurpassed knowledge of the land and its peoples — the Native Americans, the Mexicans, the Spanish, and the French — because he’d traveled the West, lived off of it on foot or muleback or horseback, from Missouri to the Northwest, down the California coast and back across what would become Arizona and New Mexico.

Little wonder, then, that Carson served the U.S. expansion west like no other. He helped map it. He helped the U.S. gain control of it. And he treated the Navajo — a tribe that in many ways he admired — shamefully in what would become known to the tribe as “The Long March” out of their territory and onto a reservation. Nine thousand Navajo were forced there under orders from the U.S. army; over 3,000 Navajo died.

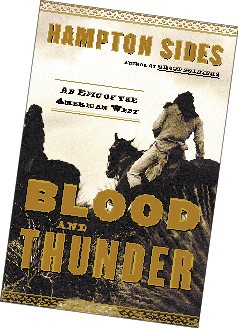

All of which, in his own lifetime, turned Carson’s exploits into the stuff of legend. “Blood and thunders,” the name given to the dime novels that featured him as the meanest, bravest Indian killer of them all, turned those exploits into the stuff of pulp fiction. His story — the real story, the whole story, America’s story — is told in the more than 400 very turnable pages of Blood and Thunder: An Epic of the American West (Doubleday), and the author is Hampton Sides, a Memphis native living in Santa Fe and the bestselling author of Ghost Soldiers, an account of American servicemen captured, imprisoned, and freed in the Philippines during World War II.

The Flyer caught up with Sides by phone during a nationwide tour and before his signing in Memphis at Davis-Kidd on October 24th. Here’s what he had to say on the writing of his latest book, on his central figure Kit Carson, and on America as nation builder, from the 19th century to today:

Flyer: First, congratulations on Blood and Thunder. What led you to embark on such a comprehensive, large-scale project?

Hampton Sides: I originally envisioned writing about the Navajo wars and the Long Walk of the Navajo people, a story that in some ways was similar to the one in Ghost Soldiers in terms of narrative arc — a story of exile, captivity, and release.

Then I asked the obvious question: If it was Kit Carson who rounded up the Navajo, who was Kit Carson? It took me four years to answer that one. It’s a better, more complicated book because of that question, but it involved going on a kind of wild goose chase. It’s a bigger story than I bargained for but a more interesting story because I took it deeper.

Who, then, was Kit Carson?

I had always thought of him as fictitious or almost fictitious — a character in a Wild West show. And in a way, he was fictitious: the hero of all those terrible books (the “blood and thunders”) and terrible movies. What’s known about Kit Carson generally is that fictitious character.

But I found that the real Kit Carson was a lot more interesting — interesting in the way he dealt with his celebrity, the way he was embarrassed by it, hounded by it, until the day he died — the expectations that celebrity created in him, the assumption that he could solve countless problems, that he could succeed at any mission. He rose to the occasion in many ways, but he always hated those expectations because what he wanted was to get home, stop wandering, settle down, have a normal life.

His sense of duty to his superiors in particular and to his country in general was profound, even when he had no personal stake in the mission handed to him, even when it came to the violence he committed against native tribes.

A sense of duty to a fault, I would say. Carson was the kind of person who, if a superior asked him to do something, he did it. That was typical of his time, typical of the army of his day, but I think Carson went beyond the call of duty in many cases. He was clearly reluctant to do some of the things he was asked to do. But in the end, he did them. And that’s really the question I wrestled with more than any other: Why did Kit Carson keep doing things he obviously was reluctant to do? And why — once he said yes to a mission, once he got going — he gave 110 percent.

How was it writing as a historian and not as a journalist?

I’m used to interviewing people. My background is journalism, magazine journalism. My first job out of college was at Memphis magazine. Ghost Soldiers I viewed as a work of journalism too, because it was primarily based on interviews.

With Blood and Thunder, though, I came up against the reality of what it means to work strictly from the documents, and I soon realized just how hard that is. There’s no “lifeline.” There’s nobody you can call. Writing this book gave me a whole new respect for historians who work strictly from archival material. There was no one to interview.

You know, I live in Santa Fe. I guess I could’ve tried to do a seance, tried some New Age method to contact the dead. Instead, I had to go at it the old-fashioned way, which meant parking myself in libraries and archives.

Did you worry about the reliability of the 19th-century accounts you were reading and depending on?

The documents themselves were spartan, spotty. A lot of the writers were semi-literate. Kit Carson was il-literate. So it’s difficult when your central character can’t even write. There’s no dependable paper trail.

Certainly, tons of people wrote about Carson during his lifetime. He dictated a lot of stuff too. So we do have documents. But they’re spread all over the place, and there’s always the problem of who Carson was dictating to. Did that person change what Carson said, project his own voice, his own interpretation of events? It was like, Will the real Kit Carson please stand up?

Plus, the Navajo culture I depict is based on an oral tradition. Like most Native Americans, their history is passed down in narratives and ceremonies. I had to work with that. I wanted to work with that. But I had to be careful how I presented it so that that oral tradition would be clear to the reader.

Has there been a reaction to Blood and Thunder among Native American readers?

I’ve had a few Navajo friends read it, and they seemed to like it a lot. But I’m sure I’ll get people from all backgrounds who will take issue with this story. It’s a multicultural minefield. And that goes not just for the Navajo — the Taos Indians too, the Comanches, the Kiowas, the Utes. All these tribal groups figure in addition to Hispanics and Anglos. And Texans … that’s a whole other tribe.

I welcome any controversy. The more we get people talking about this story, the more interesting the discussion becomes. But as for the Navajo, I certainly made every effort to understand their culture. In fact, in the book they get the last word.

There’s no denying certain parallels between the events in Blood and Thunder and the news of today: American “exceptionalism,” American interventions in the Middle East, the ongoing sectarian violence there, the cultural and religious misunderstandings or outright ignorance on the part of American foreign-policy makers. You never explicitly point to them in the book, but the comparisons are there. Do you want readers to draw those parallels?

The American strain of idealism … this wanting to be perceived not as conquerors even while we’re conquering — it’s naïve. We blunder into a world we know nothing about. We think we’ll be loved. We’ll be thought of as deliverers. We’re benevolent. Our political system is obviously the best. That naivete is still with us, I think. But then comes the realization that our intervention in other countries, other cultures, is harder than we thought it would be — that, holy shit, this is going to be complicated, bloody.

In the 19th century, we entered the Southwest, a desert world we knew nothing about. We made for wars, for animosities, for cultural and religious divisions. And now again in the Middle East we’re pledged, as General Kearny, leader of the Army of the West, said in the 19th century, “to correct all this.” U.S. intervention was then and is now a very expensive and very bloody proposition.

But I’m equally struck by American ambition and American willingness to work and sacrifice and endure … the unbelievable amounts of energy and money spent fixing the massive problems we helped to create. That’s the flip side, the good side, of the same coin.

Implicit too in the pages of Blood and Thunder is today’s immigration issue between the U.S. and Mexico.

Anyone who gets wound up about immigration — how outrageous it is that Hispanics are crossing our borders illegally and in large numbers — needs to remember that we crossed their borders long before they crossed ours. It’s hard to take a position of outrage when the U.S. swallowed an enormous chunk of land that was, you know, Mexico’s in the mid-19th century. We forget that. We’re still digesting what we swallowed in 1846 — the meanings, the moral implications.

I remember, growing up, being taught that the U.S. had never invaded a foreign country for the purpose of gaining land. I was told we’d never engaged in foreign intervention to expand our national domain. But obviously, no. The Mexican War was a blatant example of it. It was a land grab. We wanted it. We wanted it all.

You’re busy this month promoting Blood and Thunder, but do you already have plans in the works for your next book?

I want to do some magazine work first. Cleanse the palate. Clear my head. But I’ve been thinking of doing a social history of the Apollo 11 moon landing. Or research the week when Martin Luther King was killed in Memphis — piece that week together and follow exactly what led to James Earl Ray’s arrest. But to answer your question about future projects: I don’t have a definite answer yet.

I’ve spent a decade now on some pretty dark material — in Ghost Soldiers and in Blood and Thunder. I discovered what American prisoners of war in the Philippines were forced to eat to survive. I discovered what American troops in the Wild West were forced to eat to survive. I’m looking for something a little cheerier to write about, something where so many people don’t die.

Hampton Sides booksigning

Davis-Kidd Booksellers

Tuesday, October 24th, 6 p.m.