We hope you’ve been enjoying our in-depth interview with Jared “Jay B” Boyd. (Here are links to Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.) We conclude with a story about the time Boyd met one of his heroes: Stax legend Booker T. Jones.

Looking out the window onto Broadway, Booker T. Jones seemed to be seeing New York on both that day of July 12, 2023, and the many days past when he frequented the area around Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. “I would walk right through here,” he reminisced, speaking of his earliest trips to the city with the M.G.’s. “Our agent was on 57th. … We would stay at the Essex Hotel and walk past here on the way to Atlantic Records over on Broadway. And it made me question my age because I thought I remembered them building this Lincoln Center here, but I wouldn’t be that old,” he added with a wink and a grin. “I don’t think so.”

Truth be told, the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center, where a packed house had gathered to hear WYXR’s own Jared “Jay B” Boyd interview Jones, had not even been built then. Jones’ memory was correct, however — the first building on the Lincoln Center campus opened in 1962, the same year that Booker T. & the M.G.’s became a household name with the hit “Green Onions.” Now, over 60 years later, Lincoln Center was hosting Booker T. Jones: A Career Retrospective to a rapt New York audience.

Yet there were more gripping things in store that day than hearing the world’s most famous organist’s stories, for the forum was a continuation of a multifaceted series of events dubbed City Soul on the Move, three days in July when Memphis held Manhattan in the palm of its hand.

It began, as so many things do, with Tom Hanks. The actor and director is passionate about his music and, it turns out, his radio. Rock ‘n’ Soul Ichiban, with DJ Debbie Daughtry on WFMU, was a longtime favorite of Hanks, and when Daughtry launched her own internet station, Boss Radio 66 on the Tune In app, he became a DJ for the station himself.

“He’s a huge fan of Booker T.,” Daughtry says of Hanks. “He said that he would love to interview him, and then it just kind of spiraled from there. But the date that we decided on was today, and Tom couldn’t be here.” Asking around for suggested interviewers during a visit to WYXR, Daughtry landed on Boyd, who’s interviewed Jones before at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music. And WYXR’s program manager rose to the occasion, his rapport with Jones only amplified by the fact that Boyd’s mother and Jones shared a piano teacher, Elmertha Cole.

Once the interview was locked in, Daughtry says, “Lincoln Center is the one that said, ‘Why don’t we get the Stax Music Academy [SMA] to come up and play?’ And my mind just exploded!”

With the interview and SMA performance as a centerpiece of Lincoln Center’s Summer for the City series, other Mempho-centric events materialized. The night before, renowned songwriter Greg Cartwright, host of WYXR’s Strange Mysterious Sounds, played a quiet but powerful acoustic set at Union Pool in Brooklyn, accompanied by longtime Reigning Sound keyboardist Dave Amels on harmonium. The stripped-down arrangements only made Cartwright’s songs more powerful, whether they were old recorded favorites like “Reptile Style” or the more subtle songs Cartwright has been writing recently. His encore solo performance of “She’s the Boss,” dedicated to the late Rachel Nagy of the Detroit Cobras, brought the house down. Meanwhile, that same night, Boyd was featured in a lively DJ set at BierWax NYC.

Shortly after Wednesday’s interview, Cartwright and Daughtry played DJ onstage in the Lincoln Center plaza as an audience gathered, several hundred strong, bursting with expatriate Memphians. When the show began, the SMA students handled themselves with a striking professionalism, especially when Jones sat down behind the organ and led the SMA Rhythm Section through some classic M.G.’s numbers. As the students played their parts with precision and passion, backing both Jones and charismatic SMA singers Pasley Thompson, Nicholas Dickerson, Rachael Walker, Khaylah Jones, and Joi Stubbs, Jones looked them over with an unmistakable wonder, the words he’d shared with Boyd earlier still echoing: “Right now I’m full of joy. I was moved by the music and the rehearsal. … They played so well. They didn’t play the music exactly like we did. They put their own twist to it. But it felt so good.”

In a fitting warm up to this week’s 20th Anniversary of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music (see our April 27th cover story), Booker T. Jones was on the road this month, ostensibly to celebrate the 60th Anniversary of “Green Onions,” the tune that propelled Booker T. and the MG’s and Stax Records into the national spotlight. Given that the song was recorded and released in 1962, the most chronologically appropriate homage was at the museum last September, when Jones joined the Franklin Triplets, all Stax Music Academy alumni, in what would have been the record company’s old tracking room to play a short set of MG’s classics. And indeed, nothing could have topped the magic of that moment, now available as an episode of Beale Street Caravan.

But 2023 is becoming the de facto year of tributes to the classic track, cut almost as an afterthought by the group and originally dubbed “Funky Onions” by then-bassist Lewis Steinberg, until label co-owner Estelle Axton made it more palatable by changing the first word to “Green.” It was only this February, more than 60 years on, that Rhino Records re-issued the original Green Onions LP, notably the first album ever released by Stax.

Jones himself has paid tribute to the tune this year with multiple cover versions released on streaming services, all adapting the song’s basic riff to styles as disparate as Latin rock, straight rock, and country.

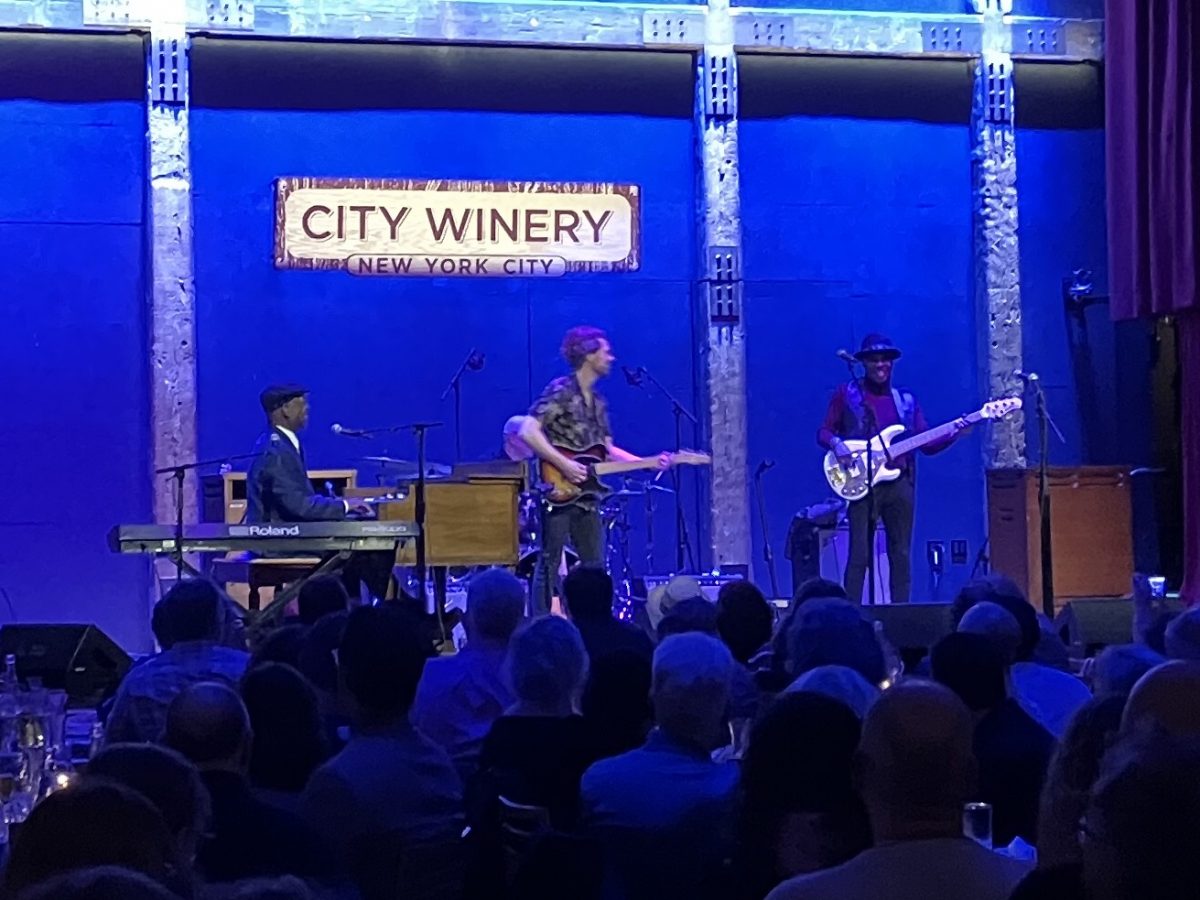

And so it was that an appearance by the famed organist, composer, and producer at New York’s City Winery on April 15th was billed as “Booker T. Jones: Celebrating 60 Years of ‘Green Onions.'” What was more surprising was the venue’s release of a special wine dedicated to both the song and the show. Sales of the dedicated vintage will benefit the Stax Museum.

That night, my date and I sampled a freshly uncorked bottle as we settled into the spacious, sold-out venue and its sweeping view of the Hudson River, the dusky spires of Jersey City looming in the distance. Soon the band, sans Jones, took the stage and began playing the descending figure of “Soul Dressing,” a cut off the MG’s album of the same name. “Wow,” exclaimed a fellow patron, representative of the night’s older demographic, “it’s not every day you get to hear the MG’s!”

I refrained from correcting him, but in my mind I heard Steve Cropper’s recent quip that “if I went out with Booker now, we’d have to call it Booker T. and the MG!” Meanwhile, I was content to take in the band before us: Dylan Jones on guitar, Melvin Brown on bass, and Ty Dennis on drums. Soon Booker T. Jones himself sauntered out to the organ, looking dapper in a blue suit and flat cap, and “Soul Dressing” began in earnest.

What followed was a tight, focused journey through not only the MG’s catalog, but other Stax hits as well. The band, while missing the inimitable swing of the original Stax house band, was on point with the arrangements. Dylan Jones carried off many of Steve Cropper’s original guitar parts faithfully, though he couldn’t resist injecting a bit of shredding when he soloed at length. His work on the the MG’s “Melting Pot” was quite venturesome, but that was in keeping with the song’s original jazz-inclined aesthetic. Brown’s bass solo on the same tune also went far beyond anything the MG’s recorded, but was imaginative and soulful nonetheless. Throughout, Booker T. Jones’ playing was as funky, tasteful, and restrained as his recorded works, even when stretching out for extended soloing on “Green Onions” in the set’s midpoint. That tune, of course, elicited the evening’s most frenzied applause.

Vocalist Ayanna Irish stepped out to put across numbers more associated with female singers, such as “Gee Whiz” and “Respect,” the latter having more to do with Aretha Franklin’s cover version than the Otis Redding original, and her approach was appropriately old-school.

Booker T. Jones sang as well, and another surprise followed his brief reminiscence. “The first time I came to New York City, in 1962, I was at the Roseland Ballroom,” he said. “With Ruth Brown and Jimmy Reed.” Already holding a guitar after singing Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine” (which he produced), he then launched into Reed’s “Bright Lights, Big City.” For a moment, you could imagine you were back home on Beale Street.

The show reached its climax with the smoldering build-up of the ostensible set-closer, “Time is Tight,” the coda of which seemed to throw the band for a loop. But as the applause died down, Jones immediately brought everyone back to Memphis. “I was standing on McLemore Avenue, and I see this guy pull up in a van from Georgia, and he starts pulling out guitar amps and suitcases and stuff and carrying them into the studio. Then he sits next to me on the organ and he wants to know if he can sing a song. And of course I say, ‘No, you can’t sing a song. You’re the valet!'” Laughter rippled through the room. “Anyway, he started singing this.” While I expected to hear “These Arms of Mine,” often associated with that story, Jones instead launched into another of Otis Redding’s great masterpieces from the early Stax era, “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now).”

At the song’s end, just as we were thoroughly melted into the floor, Jones brought things squarely into the contemporary age. “This song was written by Lauryn Hill, and it’s called ‘Everything is Everything.'” The tune, its title taken from a promotional slogan used by Stax in its heyday, and recorded by Jones in collaboration with The Roots, was the perfect way to remind us that, all anniversaries notwithstanding, this was a restless, thriving artist standing before us. Long live “Green Onions,” I thought, and long live Booker T. Jones.

We don’t often review singles in these pages, but we’ll make an exception given that this is a remake of one of, if not the, premier song of Memphis for over half a century — by its chief composer, no less.

“Green Onions” is a masterpiece one never tires of hearing, and the man who wrote its key riff and progression has always been a good sport about taking it out for a spin when he’s in town. That would be Booker T. Jones, of course, though it’s actually credited to band mates Steve Cropper, Al Jackson, Jr., and Lewie Steinberg as well, in the egalitarian spirit of both Stax Records and the 1960s.

Last year, while appearing at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, Jones treated the audience to a beautiful rendition of the tune, accompanied by three Stax Music Academy alumni, the Franklin Triplets (Sam Franklin IV, Christopher Franklin, and Jamaal Franklin). And while we often hear the tune performed in countless bombastic ways here in the Bluff City, this was clearly “Green Onions” done right: bare bones, tight, and funky. Furthermore, while speaking after the performance, Jones announced that he would soon have a new recording out to celebrate the song’s 60th Anniversary.

Jump forward to 2023, and that new track has indeed been released, though seemingly without fanfare. No press from Fantasy Records accompanied the drop, nor were there any reviews. And yet its appearance last November was perhaps one of the most significant events of 2022, in terms of its relevance to Memphis music history.

Jones himself noted the release on his Instagram page: “On this 60th Anniversary of the beloved song ‘Green Onions,’ it seems magical that my love for Latin music would be intertwined with my first musical hit. Listen to the new ‘Cebollas Verdes Cut’ out now!”

The single’s full title, “Green Onions (Cebollas Verdes Cut),” should tip off listeners that this is not your grandma’s “Green Onions,” for Jones, not one to rest on his laurels, has re-imagined the tune in a Latin boogaloo style.

And while this transforms the song’s feel considerably, the core riff and harmonies remain the same, making for a highly satisfying recasting of the song for the new century. With Melvin Brannon II on bass, Lenny Castro on percussion, Ty Dennis on drums, Jones himself on the Hammond B3, and his son, Ted, on guitar, the song retains some of the original’s glorious lack of clutter and overproduction, even as it propels itself forward on a new groove.

Careful listeners will immediately recognize that Jones has incorporated nearly all of his original solo into the new arrangement, and of course the instantly recognizable organ riff is preserved. From there, Jones takes the tune into new sonic territory, with classic Latin start-stop breakdowns and some innovative harmonies and soloing.

At the root of the tune is a bass line more in the vein of what some call the New Orleans “Spanish tinge.” One might almost mistake it for a remake of “Black Magic Woman” for a minute, until Jones enters with that inimitable solo. From there, Ted Jones brings a decidedly more progressive quality to the guitar solo, also echoing Santana.

If you don’t care for the sound of that, skip the radio-friendly A side and go straight to the deep cut, a much longer edit that plays more fully on the possibilities of mixing the boogaloo beat with the organ. Indeed, there is no guitar solo here, only the extended riffing and soloing of Jones, a master of the Hammond B3.

In all, this is a satisfying gem of a single, and, given the city’s influx of Latin American emigres since the original single dropped, a welcome update to fit current demographics. One can only hope that it becomes the standard of this century, carrying on that slinky, earthy groove well into the next.

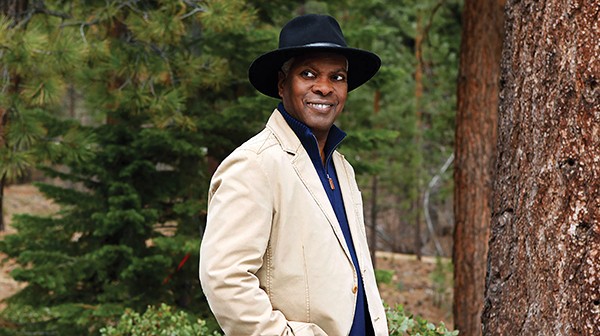

Booker T. Jones is such an iconic Memphian that he’s still identified with his hometown a half century after moving to California. And, that relocation notwithstanding, he’s an enthusiastic advocate of all things Memphis, including the Memphis of his youth, and the supportive community he continues to find here today.

So, it’s wholly appropriate that Jones will be inducted into the Memphis Music Hall of Fame (MMHOF) on Thursday, September 15th. While Booker T. & the MG’s were inducted as a group in 2012, this year’s honor will serve as a recognition of Jones’ accomplishments as an individual, outside of that seminal band, including the many songs he’s penned, recorded, arranged or produced since leaving Stax Records. As such, it’s as much a recognition of the California Jones as the Memphis Jones.

Jones will be performing at Thursday night’s ceremony. In addition to Jones, the 2022 inductees include the late blues and jazz saxophonist, composer, arranger, and educator Fred Ford, Grammy-winning producer and engineer Jim Gaines, American Sound Studios keyboardist, singer, and Grammy winner Ronnie Milsap, former chair of Elvis Presley Enterprises Priscilla Presley, Sun Records artist, songwriter, and producer Billy Lee Riley, Stax artist and Grammy-winning soul giant Mavis Staples, and the iconic drummer for Jerry Lee Lewis and other Sun artists (as well as singer and producer) J.M. Van Eaton. Gaines, Jones, Milsap, Presley, and Van Eaton are all scheduled to attend, while local favorites Reba Russell and John Paul Keith will also perform.

All in all, very good company for Booker T. Jones. Anticipating his imminent homecoming, Jones recently spoke at length with the Memphis Flyer from his home in northern California. Only one day after a mass shooter terrorized the city, our hearts were heavy, yet Jones helped put the day’s events in perspective.

Memphis Flyer: How strange that Memphis is in the headlines for its crime, just when you’ll be coming here to celebrate its positive, musical side.

Booker T. Jones: My condolences to the families. And I hope everybody does something positive in the wake of that. Do something nice for somebody, or for yourself. Try to do something that’s the opposite of that negative energy. Something positive. It’s a huge tragedy.

I was just thinking how appropriate your song, “Representing Memphis,” featuring Sharon Jones and Matt Berninger, is at this moment. It really celebrates the neighborhoods, sights, and sounds of the city.

Well, it’s good to mention Sharon’s name. She was one of the most positive people I’ve known. It was wonderful meeting Sharon. She’s from Brooklyn, I think. She was a very neighborhood-friendly type of person.

“Representing Memphis” also featured Matt Berninger on vocals.

Yeah, he’s another good friend of mine. He’s in a band called The National.

Since you moved to California 50 years ago, it seems you’ve done one collaboration after another.

Yeah. Of course, I miss Memphis. I wouldn’t have been able to go to California if Memphis hadn’t been so good to me. I have a lot of friends there. I’m coming there in a few days, and it’s going to be great to see my family. My family’s from Red Banks, Mississippi and Holly Springs, Mississippi, and they’re all coming. So, it’s going to be great.

How does it feel to return to the Stax building?

I tell you what, Alex: That is hallowed ground. It just is. I remember when I went back a few years after they had torn down the building, and I picked up some bricks and brought them back to California. Because when you walk in the area of 926 East McLemore Avenue, it’s just great. That’s an indication of the spirit of Memphis. It’s all over that town.

It seems you’ve become more appreciative of Memphis in recent years, more so than in the ’70s and ’80s.

That’s true. I have embraced it more, emotionally. Intellectually, I’m maturing. I’m 77 years old. Hopefully I’m maturing somewhat. And just realizing and recognizing who I am and where I come from.

You even named your new record label after the street you grew up on… Edith Street.

Yeah, that’s where it started. That’s another place that’s emotional for me to go back to.

Being inducted into MMHOF apart from the MG’s must be very meaningful to you, after your struggle to get more recognition as an individual before you left Stax.

It is, it’s a really big deal to me. I owe so much to so many people in Memphis who gave me so much at such a young age. And I had so many mentors. And there was such a spirit of giving in my community. In the music community at school, at church, in the neighborhood. So I’m a result of that giving. And it’s a lesson to me. I’m just very fortunate.

It’s ironic, maybe that spirit of giving and support also gave you the strength to break away from Stax.

Yeah, it definitely was a positive/negative, yin/yang type of thing, and of course as soon as I got to California, I had other mentors. Namely Quincy Jones, who was right there, introducing me to this kind of music, that kind of music. And I was immediately surrounded by other mentors. Herb Alpert and so many others. But a lot of kids don’t get a chance to do that. They don’t have a recording studio around the corner from their house. They have to go to Nashville or New York or Los Angeles if they want to be in music. So, I was fortunate that I was born right there in Memphis with a studio three blocks away.

It’s interesting that you mention Quincy Jones. I saw a documentary where you spoke about one particular moment, hearing Ray Charles’ “One Mint Julep” on the radio, which led you to pursue the Hammond organ.

That was the moment. I was on McLemore Avenue, listening to the radio, and I was thinking ‘Oh, what great horns!’ And then I heard the organ and thought, ‘Wow, that’s such a cool sound!’ It wasn’t a sound you heard very much. And I thought if I could just do that, I’d be happy. And I am happy. And it was Quincy’s band on that record. Quincy wrote the arrangements, and Ray was actually a saxophone and organ player in Quincy’s band. Quincy was the man who put all that together.

It was kind of coming full circle, when you connected with him personally later in life. That must have meant a lot.

Yeah. He was a mentor. And he was one of those guys like Willie Mitchell. Willie would take young guys like me and put them up on stage and just try them out. That’s what he did with Mabon ‘Teenie’ Hodges, who was a good friend of mine. Willie did that with me, on the bass. Willie is a really good example of that Memphis spirit I’m talking about. And of the mentors I had there.

People often think of Stax Recrods and Hi Records as competitors, but there was a whole local scene that transcended the labels.

Oh yeah, directly. Well, Willie let me play baritone sax in his band, and baritone sax is the instrument that got me into Stax. David Porter took me into Stax to play baritone sax on “Cause I Love You.”

One thing you mention in your autobiography was a friend from Egypt, Mina E. Mina, and the female singer whose work he introduced you to.

Uma Kalthoum. My Egyptian friend in Malibu was a disciple of hers, and we would sit and just be moved by her voice.

California was really a world destination, wasn’t it? So many of these cultures were converging and influencing pop music.

Exactly.

Are there recordings of yours that show more of a world music influence?

Definitely so. So many different kinds of influences were right there, close together. Bill Withers came to California, Leon Russell, and the Brothers Johnson. Quincy was crazy about them. He had a special spot in Hollywood — a room at 1416 North La Brea, right at the corner of La Brea and Sunset Boulevard. And that was sort of a nexus. It was A&M studios, where his office was. So, if you were an arranger — and that’s what I was, an arranger/producer; I played a lot of sessions — his place became a go-to place for a lot of people.

Are you at work on a new album now?

Yeah. It’s the 60th Anniversary of “Green Onions,” and that was the song — I wouldn’t be talking to you if I hadn’t stumbled onto recording that song. That was 60 years ago, so I’m going to do a tribute to that. It was June, 1962 when we recorded it, and I was supposed to be in church. It was a Sunday, I remember. Memphis changes on Sunday morning. Or, at least it did back then. Everyone was in church by [10 a.m. or 11 a.m.]. If you weren’t there, you were doing something kind of strange. I think we were supposed to play on a session. Steve remembers more about it. It was a session that got called off or finished early, and then we had free studio time.

And “Green Onions” was kind of an afterthought, the B side?

Exactly. And “Behave Yourself” was me trying to imitate Ray Charles. I had a little band at a club on South Parkway, and Errol Thomas was playing bass, and Devon Miller on drums. And I would always start with that, because of Quincy and Ray and that B3 sound; and I was trying to imitate Ray, so I came up with that blues, “Behave Yourself.” Why would they just have an M1 organ sitting there that day? It was my dream. It was amazing! I had actually used it once before, because I played on William Bell’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” and also I had played for Prince Conley in that room when I was a young kid. Charlie Musselwhite reminded me of that. He was a friend of mine from Mississippi.

Was it the track, “Going Home”?

That was it! I remember that day because I played on that song, but the room was so big, I never did get to meet Prince Conley the whole time.

You write about Maurice White, founder of Earth, Winde & Fire, in your book. Did you guys ever connect in later years? Did you play together once you were established artists?

Oh yeah! He loved to play tennis and when I moved out to the San Fernando Valley, he would come out there and play tennis with me, and ridicule me [laughs]. We were good friends in high school. I think I met him in 8th grade at Porter [Junior] High. And I was the only student with a key to the band room at Porter. So, he walked in and said, ‘Hi, I’m Maurice White.’ His destination after school was my house. And we would play tunes by the Jazz Messengers, or whatever, because I had a record player.

Maurice didn’t really have a family. His grandmother was all he had. And I never did even see his mother until he graduated from high school. That was a good, tight friendship between me, and David Porter, and Maurice. That’s how it all started. Maurice on drums and Richard Shann, who played piano, and I had a bass.

Did you dabble on saxophone in that trio?

I probably did, because I always tried to play reeds: oboe, clarinet. I played clarinet in the band, and the school had a baritone sax.

It sounds like Richard Shann was a great jazz player.

Oh, yeah. He was the true musician of the three of us, the most dedicated. He lived way out in South Memphis, and he would walk to my house to jam with us.

Whatever became of him?

He passed years ago.

It makes me wonder if you and Maurice had ever played music together after you left Memphis. But it sounds like you mainly played tennis?

You know, he was like a brother to me. My dad brought his drums home from AMRO Music, his first drum set. But Maurice was missing his family so, as soon as he graduated from high school, he moved to Chicago. And then Ramsey Lewis heard him play somewhere, and Maurice was gone, basically. He was unavailable. Of course, you know I wanted him to be a drummer in my band, and that would never happen. He started Earth, Wind & Fire and they were instant stars, and he got such a good position in Chicago, and I don’t remember him ever coming back to Memphis.

A lot of people don’t realize he was from Memphis.

That’s amazing, because he was. LeMoyne Gardens. I doubt if I would have been able to make it to Stax if I hadn’t known Maurice. My dad used to drive me, Maurice, and Shann to the middle of Arkansas, nowhere, til 10:00 at night, to play a little gig, playing for four/five people, then drive us back at 2 in the morning. That’s what we did. The bass, the drums, the whole thing in the car, it was a sight! In my dad’s ’49 Ford.

Your dad sounds like a prince of a man.

Yeah, he was the sponsor. He was the reason it all happened. He drove my friends around. He was the guy. I was lucky there. Maurice didn’t have any of that, no mother or father. So, he came to my house.

He’s already been inducted into the MMHOF, so you guys will be side by side now.

That’s good to hear!

The 2022 Memphis Music Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony takes place Thursday, September 15, 7 p.m., at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets are on sale now for only $30, and are available at www.ticketmaster.com or the Cannon Center box office.

The young student knew how far the guidance of a good music teacher could take him. “It was assumed that you would play jazz,” he wrote many years later. “Memphis’s young musicians were to unwaveringly follow the footsteps of Frank Strozier or Charles Lloyd or Joe Dukes in dedicating their lives to the pursuit of excellence.” The young man had a jazz combo with his friend Maurice. “Because he cosigned the loan for the drums, loaned us his car, and believed in us, Maurice and I were both deeply indebted to Mr. Walter Martin, the band director. You could hear a reverence in his voice when he spoke Maurice’s name.”

Yet he gained more than material assistance from his high school education. “I took music theory classes after school. Professor Pender was the choral director at Booker T. Washington, and like the generous band directors, Mr. Pender made an invaluable contribution to my musical understanding.” Pondering his lessons on counterpoint, the student thought, “What if the contrapuntal rules applied to a twelve-bar blues pattern? What if the bottom bass note went up while the top note of the triad went down, like in the Bach fugues and cantatas?” And so, sitting at his mother’s piano, he wrote a song.

He had only just graduated when the piece he composed came in handy. Though it was written on piano, he suddenly found himself, to his amazement, in a recording studio, playing a Hammond M-3 organ. He thought he’d try his contrapuntal blues on this somewhat unfamiliar instrument. Why not?

That’s when the magic went down on tape, and ultimately on vinyl. It was an unassuming B-side titled “Green Onions.” To this day, the jazz/blues/classical hybrid that sprung from a teenager’s mind remains a cornerstone of the Memphis sound. The teenager, of course, was Booker T. Jones, co-founder of Booker T. and the MGs. As he reveals in his autobiography, Time is Tight: My Life, Note by Note, his friend, so revered by the band director at Booker T. Washington High School, was Maurice White, future founder of Earth, Wind & Fire. Their lives — and ours — were forever changed by their high school music teachers.

It’s a story worth remembering in these times, when the arts in our schools are endangered species. And yet, while you don’t often hear of band directors cosigning loans or handing out car keys anymore, they remain the unsung heroes of this city’s musical ecosystem. The next Booker T. is already out there, waiting to take center stage, if we can only keep our eyes on the prize.

Mighty Manassas

The big bang that caused the Memphis school music universe to spring into being is easy to pinpoint: Manassas High School. That was where, in the mid-1920s, a football coach and English teacher fresh out of college founded the city’s first school band, and, right out of the gate, set the bar incredibly high. The group, called the Chickasaw Syncopators, was known for their distinctive Memphis “bounce.” By 1930, they’d recorded sides for the Victor label, and soon they took the name of their band director: the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra. They released many hit records until Lunceford’s untimely death in 1947.

Nearly a century later, Paul McKinney, a trumpet player and director of student success/alumni relations at the Stax Music Academy (SMA), takes inspiration from Lunceford. “He founded his high school band and took them on the road, with one of the more competitive jazz bands in the world, right there with Count Basie and Duke Ellington. And I’ve tried to play that stuff, as a trumpet player, and it’s really, really hard! And then one of the best band directors in Memphis’ history, after Jimmie Lunceford, was Emerson Able, also at Manassas.”

Under Able and other band directors, the school unleashed another wave of talent in the ’50s and ’60s, a series of virtuosos whose names still dominate jazz. One of them was Charles Lloyd, who says, “I went to Manassas High School where Matthew Garrett was our bandleader. Talk about being in the right place at the right time! We had a band, the Rhythm Bombers, with Mickey Gregory, Gilmore Daniels, Frank Strozier, Harold Mabern, Booker Little, and myself. Booker and I were best friends, we went to the library and studied Bartok scores together. He was a genius. We all looked up to George Coleman, who was a few years older than us — he made sure we practiced.”

Meanwhile, other talents were emerging across town at Booker T. Washington High School, which spawned such legends as Phineas Newborn Jr. and Herman Green. It’s no surprise that these players from the ’40s and ’50s inspired the next generation, like Booker T. Jones, Maurice White, or, back at Manassas, young Isaac Hayes, yet it wasn’t the stars themselves who taught them, but their music instructors. Although they didn’t hew to the jazz path, they formed the backbone of the Memphis soul sound that still resounds today. As today’s music educators see it, these examples are more than historical curiosities: They offer a blueprint for taking Memphis youth into the future.

Making the Scene

And yet the fact that such giants still walk among us doesn’t do much to make the glory days of the ’30s through the ’60s within reach today. For Paul McKinney, whose father Kurl was a music teacher in the Memphis school system from 1961 to 2002, it might as well be Camelot. And he feels there’s a crucial ingredient missing today: working jazz players. “All the great musicians that came out of Memphis in the ’50s and ’60s were a direct result of the fact that their teachers were so heavily into jazz. The teachers were jazz musicians, too. We teach what we know and love. So think about all those teachers coming out of college in the ’50s. The popular music of the day was jazz! And the teachers were gigging, all of the time.”

Kurl, for his part, was certainly performing even as he taught (and he still can be heard on the Peabody Hotel’s piano, Monday and Tuesday evenings). “Calvin Newborn played guitar with my and Alfred Rudd’s band for a number of years,” he recalls. “We played around Memphis and the surrounding areas.” That in turn, his son points out, brought the students closer to the world of actual gigs, and accelerated their growth. In today’s music departments, Paul says, “there are not nearly as many teachers who are jazz musicians. As a jazz trumpeter and a guy who grew up watching great jazz musicians, that’s what I see. Are there a few band directors who play it professionally? Yes. But there aren’t many.

Trombonist Victor Sawyer works with SMA but also oversees music educators for the Memphis Music Initiative (MMI). Both nonprofits, not to mention the Memphis Jazz Workshop, have helped to supplement and support public music programs in their own ways — SMA by hosting after school classes grounded in local soul music, MMI by helping public school teachers with visiting fellows who can also give lessons. Sawyer tends to agree that one important quality of music departments past was that the teachers were working jazz musicians. “All these people from the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and before have stories of going to Beale Street and checking out music and having the opportunity to sit in. I feel like the high schools in town today aren’t as overtly and intentionally connected to the music scene. So you’re not really seeing the pipelines that you did. When you don’t have adults who will say, ‘Come sit in with me, come see this show,’ you lose that natural connectivity. So you hear in a lot of these classes, ‘You can’t do nothing in Memphis. I’ve got to get out of Memphis when I graduate.’ That didn’t used to be the mindset because the work was here, and it still is here; it’s just not as overt if you don’t know where to look.”

Music Departments by the Numbers

A sense of lost glory days can easily arise when discussing public education generally, as funding priorities have shifted away from the arts. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calls the years after the 2008 recession “a punishing decade for school funding,” and Sawyer contrasts the past several decades with the priorities of a bygone time. “After World War II, there was a huge emphasis on the arts. Every city had a museum and a symphony. Then, people start taking it for granted, and suddenly you have all these symphonies and museums that are struggling. The same for schools: There’s less funding. When STEM takes over, arts funding goes down. The funding that the National Endowment of the Arts provides for schools has gone down dramatically.”

Simultaneously, the demographics of the city were shifting. “Booker T. Washington [BTW], Hamilton, Manassas, Douglass, Melrose, Carver, and Lester were the only Black high schools in the late ’50s/early ’60s. So of course people gathered there,” Sawyer says. “You’d have these very tight-knit cultures. Across time, though, things became more zoned; people became more spread out. Now things are more diffuse.”

Not only did funding dry up, enrollment numbers decreased for the most celebrated music high schools. Dru Davison, Shelby County Schools’ fine arts adviser, points out that once people leave a neighborhood, there’s not much a school principal can do. “What we’ve seen at BTW is a number of intersecting policies — local, state, and federal — that have changed the number of students in the community. And that has a big impact on the way music programs can flourish. And more recently, it’s been an incredibly difficult couple of years because of the pandemic. Our band director at Manassas, James McLeod, passed away this year. So we’re working to get that staff back up again, but the pandemic has had its toll on the programs.”

Davison further explains: “The number of the kids at the school determines the number of teachers that can work at that school. So at large schools like Whitehaven or Central, that means there are two band directors, a choir director — fully staffed. But if you go to a much smaller school, like BTW and Manassas, the number of students they have at the schools makes it difficult to support the same number of music positions. That’s a principal’s decision.”

The Culture of the Band Room

Even if music programs are brought back, the disruption takes its toll. One secret to the success of Manassas was the through-line of teachers from Lunceford to Able to Garrett and beyond. Which highlights a little recognized facet of education, what Sawyer calls the culture of the classroom. “When you watch Ollie Liddell at Central High School or Adrian Maclin at Cordova High School, it’s like, ‘Whoa! Is this magic?’ These kids come in, they’re practicing, they know how to warm up on their own. But it’s not magic. These are master-level teachers who have worked very hard at classroom culture. The schools with the most thriving programs have veteran teachers who have been there a while, so they have built up that culture.”

In fact, according to Davison, that band room culture is one reason music education is so valuable, regardless of whether or not the students go on to be musicians. “I’m just trying to help our teachers to use the power of music to become a beacon of what it means to have social and emotional support in place. As much as our music teachers are instilling the skills it takes to perform at a really high level, they’re also creating places for kids to belong. That’s been something I’ve been really pleased to see through the pandemic, even when we went virtual.” Thus, while Davison values the “synergy” between nonprofits like SMA or MMI and public school teachers, he sees the latter as absolutely necessary. “We want principals to understand how seriously the district takes music. It’s not only to help students graduate on time but to create students who will help energize our community with creativity and vision.”

And make no mistake, the music programs in Memphis high schools that are thriving are world-class. By way of example, Davison introduces me to Kellen Christian, band director at Whitehaven High School, where enrollment has remained reliably large. With a marching band specializing in the flashy “show” style of marching (as opposed to the more staid “corps” style), Whitehaven has won the High Stepping Nationals competition four times. (Central has won it twice in recent years.) Hearing them play at a recruiting rally last week, I could see and hear why: The precision and power of the playing was stunning, even with the band seated. Christian sees that as a direct result of his band room culture. “Once you have a student,” he says, “you have to build them up, not making them feel that they’re being left out. So we’re not just building band members; we’re building good citizens. They learn discipline and structure in the band room. That’s one of the biggest parts of being in the band: the military orientation that the band has.”

Lured into Myriad Musics

But Christian, a trumpeter, is still a musician first and foremost, and he sees the marching band as a way to lure students into deeper music. “Marching band is the draw for a lot of students,” he says. “When you see advertisements for bands from a school, you don’t see their concert band, you don’t see their jazz bands. The marching bands are the visual icons. It’s what’s always in the public eye.” But ultimately, he emphasizes, “I love jazz, and marching band is the bait. You’ve got to use what these students like to get them in and teach them to love their instrument. Then you start giving them the nourishment.”

As Sawyer points out, that deeper nourishment may not even look like jazz. “Even with rappers, you’ll find out they knew a little bit about music. 8Ball & MJG were totally in band. NLE Choppa. Drumma Boy’s dad is [retired University of Memphis professor of clarinet] James Gholson!” Even as Shelby County Schools is on the cutting edge of offering classes in “media arts” and music production, a grounding in classic musicianship can also feed into modern domains. True, there are plenty of traditional instrumentalists parlaying their high school education into music careers, like David Parks, who now plays bass for Grammy-winner Ledisi and eagerly acknowledges the training he received at Overton High School. But rap and trap artists can be just as quick to honor their roots. “Young Dolph, rest in peace, donated to Hamilton High School every year because that’s where he went,” notes Sawyer. “Anybody can do that. Find out more about your local school, and donate!”

Reminiscing about his lifetime of teaching music in Memphis public schools, Kurl McKinney laughs with his son about one student in particular. “Courtney Harris was a drummer for me at Lincoln Junior High School. He’s done very well now. Once, he said, ‘Mr. McKinney, I’ve got some tapes in my pocket. Why don’t you play ’em?’ I said, ‘What, you trying to get me fired? All that cussin’ on that tape, I can’t play that! No way! I’m gonna keep my job. You go on home and play it to your mama.’

“But I had him come down to see my class, and when he came walking in, their eyes got as big as teacups. I said, ‘Class, this is Gangsta Blac. Mr. Gangsta Blac, say something to my class.’ So he looked them over and said, ‘If it hadn’t been for Mr. McKinney, I would never have been in music.’” Even over the phone, you can hear the former band director smile.

Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Booker T. Jones and band with Carla Thomas

“My first guitar was a Sears Silvertone,” quipped Booker T. Jones during his appearance at Crosstown Theater Saturday. Looking up at the walls around him, he added, “I must have bought it right here.”

Crosstown Concourse, of course, was then the regional warehouse and retail center for Sears. He went on to recall how he quit buying records at Sears after he discovered the Satellite Record Shop, the storefront at the entrance to Stax Records in its heyday. At Sears, he noted, you couldn’t hear the record until you bought it. “But Steve Cropper was happy to play records for you.”

Such are the perks of hearing one of the progenitors of classic soul play his hometown, where, once upon a time, lightning was captured in a bottle, or at least on vinyl. And Jones seemed to revel in the memories.

But the magic of such anecdotes paled before the majesty of the music, unerringly played by Jones and his band (which included his son Ted on guitar, Melvin Brannon, Jr. [aka M-Cat Spoony] on bass, and Darian Gray on drums). Time stood still as the sounds of Jones on the Hammond organ, complete with rotating Leslie speaker, filled the auditorium with the harmonies known from so many classic records.

Though Jones’ latest album, Note by Note, surveys tunes from across his lifetime as a player and a producer, Saturday’s set was decidedly Memphis-heavy, with a heaping dose of originals by Booker T. & the M.G.’s. There was “Green Onions” in all its minimalist glory, and “Time Is Tight,” complete with its powerful coda. “Hip-Hug Her” also was honored, albeit with a twist: flowing lyrics rapped over the tune by Gray.  Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Booker T. Jones and son Ted Jones

“And now, here’s a piece by George Gershwin,” Jones noted, before launching into the M.G.s’ arrangement of “Summertime,” as perfect a showcase of his organ mastery as any of their cuts.

But the legacy of that Silvertone guitar was also alive and well, as Jones picked up a Telecaster and sauntered to the front of the stage from time to time, delivering very personal interpretations of “Hey Joe,” a la Jimi Hendrix, “Purple Rain” by Prince, and others. At times, he sang sublime harmonies with his son.  Alex Greene

Alex Greene

Booker T. Jones on guitar

But the most sublime harmonies of the night came when Jones called “an old friend” to the stage, none other than the Queen of Memphis Soul, Carla Thomas. Jones, noting the importance of the Thomas family, and especially Carla’s father Rufus, described seeing the movie Baby Driver and unexpectedly hearing her sing in the soundtrack. Then they launched into “B-A-B-Y,” one of Carla’s greatest Stax sides. She was in fine voice, her delivery full of her trademark sweetness and wit. It was a luminous moment, with Carla, Jones and the band breaking out into beaming smiles throughout.

It was a dramatic moment, especially because Jones typically approached each song with a solemnity that seemed to exhort the audience to listen with care. And listen they did, the entire room rapt with adoration for the grooves and the moves that helped put Memphis on the map.

Opening the set were students from the Stax Music Academy, who did right by such classics as “Soul Man,” “Soul Girl,” “When a Man Loves a Woman,” and even Peter Gabriel’s Stax-influenced “Sledgehammer.” For those who slept on it, let it be known that Memphis Soul is alive and well and kicking.

In covering the Memphis music beat, I talk to a lot of inspired artists — composers, singers, and performers who have rattled the world with their choice of notes, their tone. And they’ve worked in a variety of genres as sprawling as the city itself. But through all the conversations, all the life stories that come pouring out of them, there’s a common thread: church music.

Herman Green, recalling the days of his youth in the 1930s, before he’d ever imagined mastering the saxophone: “I played guitar with a blind pianist man named Lindell Woodson, who played piano for my stepfather’s church. I don’t even know how he could tell what key it was, but he’d get all over that piano like Art Tatum. And it was the Church of God, [claps and sings], you know? It was that kind of thing.”

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Fellowship Baptist Church

Booker T. Jones, on his earliest years as a musician: “I want you to mention Merle Glover. She was the organist, and she played the pipe organ. That was the first organ I ever played, at Mt. Olive Cathedral, over by Porter School on Vance Avenue. I was the pianist for the men’s Bible class. I was there at 9 o’clock every Sunday morning for years.”

William Bell, reminiscing about “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” his first hit for Stax Records: “At that particular time, I had been singing secular music in clubs, but the training and the background was strictly gospel. Most soul singers and country singers, we all came out of church … You sang with the choir for a while, and those choir rehearsals taught you how to sing in tune and treat a lyric and express an idea. So all of that helped as we created a career.”

DJ Squeeky, producer of 8Ball & MJG and Young Dolph, recalls growing up playing drums at First Baptist Church on Beale Street, where his mother has always gone. His uncle was “cold” — a master of any instrument in the church, able to jump in and accompany any singer, on any song.

MonoNeon

MonoNeon, trailblazing funk and avant garde bassist: “Eventually I started playing in church. That’s where I really got most of my skill from. Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church on Knight Arnold.”

Vaneese Thomas, noting how she and siblings Carla and Marvell grew up a little differently from most: “Our church was not the gospel experience people expect from Memphis. We grew up in a very straight-laced Baptist church. So we sang hymns and anthems.”

And that’s just a small sampling. Everywhere you turn, the influence of African-American churches on the Memphis sound — even in the era of hip-hop — is inescapable. The church crops up in nearly every musician’s biography, yet remains under-recognized for what it is: a crucible for musical talent and skill without parallel.

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Minus Red Productions/Candied Yam Music

Kirk Whalum

In order to dig a little deeper into this milieu, I could think of no better guide than Kirk Whalum, composer, producer, and sideman extraordinaire, whose command of the saxophone has carried the tones and phrasing honed in his father’s church across the world.

“It’s that thing that we take for granted many times, but other people go, ‘Well, that’s just exactly what I need,'” Whalum reflects. “Whether it’s Quincy Jones — as many sessions as I’ve done with him — or many other artists, they hear Memphis in my sound. Not just Memphis, but Memphis church. And it’s specifically the black church. I mean, Aretha Franklin — her dad was pastoring a black church here. And, you know, Maurice White and David Porter were singing in a black church group in their formative years. So those are the things I’m talking about when I say it’s all about that soul that you get from that place. And that makes its way into art.”

If Whalum takes a philosophical perspective on the idea, perhaps it’s a family thing, given that his late father, Kenneth Whalum Sr., once was pastor of the Olivet Baptist Church on Southern Avenue, and his brother, Kenneth Jr., now presides over that church’s latest incarnation, the New Olivet Baptist Church. It’s only natural that Kirk looks beyond the more superficial influence of, say, the gospel repertoire.

“I think it’s more of an approach. In white culture — what represents Western white culture? I think ballet. In ballet, the more intense you get, the higher you get: literally, physically higher. And the pinnacle of ballet is en pointe. You’re on your toes, you know, and you’re reaching for the sky. And just the opposite applies to African music. When you hear people talking about getting down, it’s like the pinnacle of the African musical experience: You’re almost on the floor. You’re bending down all the way.

“I think that’s a good metaphor for the approach that you get from black music. It’s not about someone ‘playing soulful,’ it’s about believing in something and being a part of something and someone. In this case, Jesus. That brings about a completely different approach. It’s not so much the technique or those other things that we all aspire to. The main thing is that feeling, that conviction.”

Yet there’s another force at work here as well, something larger than oneself that players can reach for and one that often goes hand in hand with the church: family. This too arises over and over again in Memphis musicians’ stories, with such a diversity of what “family” actually means that it need not be reduced to a simple Norman Rockwell image.

Barry Campbell with John Black and Austin Bradley

Musical families have marked the evolution of Memphis music since before that history was written. Herman Green never knew his biological father, Herman Washington Sr., a player in W.C. Handy’s band who was murdered when Green was only 2 years old. But his stepfather, Rev. Tigner S. Green, played a major role in his love of music. Other Memphis families were even more legendary: the Newborns, the Jacksons, and the Thomases, from father Rufus to his three children, to name but a few.

The Whalums, of course, are a formidable musical force in this town, yet they are far from the only dynasty springing from a fortuitous union of both religious and filial continuity. Take the Barnes family: Deborah Gleese, daughter of Rev. James L. Gleese, was, for a time, a Raelette, one of the background singers for Ray Charles, before she married gospel singer Duke Barnes and family life demanded that she leave touring behind.

Converting to the Seventh Day Adventist Church, the couple sang and played around Memphis regularly, ultimately incorporating their children into the show. Today, the Sensational Barnes Brothers, brothers Courtney and Chris, are a gospel act in their own right on the newly minted Bible & Tire Recording Company, while their older brother Calvin is the Minister of Music at the Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church.

Seeing him lead the band this past Sunday was an excercise in polished euphoria. From the mellow background passages, bubbling under Dr. Geno Gibson’s sermon, to the band and choir syncing flawlessly with a spritely drum machine and video projections, the service was a master class in stage craft. In the context of references to young congregation members who had recently been murdered, and in Gibson’s unflinching critique of the New Jim Crow, the music’s shimmer was a welcome blast of ecstatic community.

Jonny Pineda

Jonny Pineda

Jason Clark

Mostly, the service created a spirit of inclusiveness, and, it turns out, the church band is itself a testament to such openness. Calvin Barnes remained a Seventh Day Adventist for years when he began playing for Olivet Fellowship, before finally joining the church where he works nearly a decade ago. This is not uncommon. Jason Clark, executive director of the Memphis-based Tennessee Mass Choir, puts it this way: “Sometimes it’s difficult to find the level of talent you need right within a congregation. Sometimes you have to be a part of a congregation that’s willing to support the music industry financially, and that doesn’t always come from your home church.”

In the case of the Olivet Fellowship (which splintered from the New Olivet Baptist Church some years ago), that openness to outside talent extended to allowing one young drummer to rehearse his secular band in the church during off-hours. Calvin Barnes recalls meeting the drummer’s bass player, a kid named DJ, whose father was a well-known bassist already. “The first time I met him, he was playing with this little group, kids really, and some of them were members of my church. DJ was probably around 12 and came in with his bass bigger than him, and when he played it was like ‘Oh. My. God.’ He wasn’t as good as he is now, but he was playing like a grown man. At that time he was super shy. But when the church ended up losing our bass player, we said, ‘Why not DJ?'”

Though DJ didn’t know the formidable gospel repertoire, he soon mastered it. Calvin nurtured both his idiosyncracies and his ensemble chops. “I really took him under my wing,” says Barnes. “And on the music tip, I would challenge him. Because he’s always been that avant garde-in-the-making type. So when the pastor gets up to preach, musicians typically go off to the side because they’re done for the moment. They just chill. Not him. He would sit there in his chair, turn his volume down, and start practicing bass. He’d do that through the entire sermon, every week. Over and over and over. And I would tell him, ‘You’re gonna be major.'”

Calvin Barnes, Minister of Music at Olivet Fellowship Baptist Church, on keyboards

As he coached the young bassist, little did Barnes realize that DJ’s idiosyncracies were what would lead him to greater renown. Some years later, DJ began posting YouTube videos of his more off-the-wall music, under the name MonoNeon. One such video caught the ear of Prince, who flew him to Paisley Park in Minneapolis to jam and record several times before the mega-star’s untimely death. Today, MonoNeon continues to ride that momentum, both with his own albums and in collaborative bands like Ghost-Note.

Church bands, it seems, are especially open to child prodigies. Jason Clark remembers well one young talent in particular: “When I played at Abundant Grace, close to 28 years ago, there was a young guy named Stanley Randolf, who was 9 years old. He was one of the most phenomenal drummers that I had ever heard. Now he’s Stevie Wonder’s drummer, to this day! We have quite a bit of those stories here.”

Clark himself is no stranger to being a prodigy nurtured by both a musical family and the church. Both playing in a church band and directing the Tennessee Mass Choir, which pulls talent from across the state to Memphis, he seems to have been destined for a life in music. “The choir was actually started by my mother, Fannie Cole-Clark, back in 1990. Next year we’ll be celebrating 30 years. Our mother passed away six years ago, so it was handed over to me when she passed. A lot of people remember her from back in the day, when she started the Fannie Clark Singers, produced by the late, great Willie Mitchell. It was a gospel group. I actually started out playing tambourine for the Fannie Clark Singers when I was 6 years old.”

Clark went off to a life in religious music and credits his success, in part, to time he spent at one of the city’s most pre-eminent musical ministries, Mississippi Boulevard Christian Church. “Dr. Leo Davis is one of the best Ministers of Music that I’ve worked under,” he says. “I know he single-handedly trained a lot of musicians here in the city. And to this day, they have probably one of the top five bands in the city. I think that’s due to his leadership.”

Now Clark’s an accomplished keyboardist, while his brother Jackie is a go-to bass player for the likes of Kirk Whalum and others. But for Clark, the luck of being born among musical folk is not a prerequisite for thriving in the church music scene. “No, not really,” he says. “There of course are a few like that, but there are some who are just gifted. There are some who went to school. That’s the beauty of church musicians. You get such a variety. That’s why our genre is more diverse than any other style of music. It encompasses jazz, to pop, to that gritty bluesy feel, to classical. I really credit that to the fact that not everyone grew up in church, just playing gospel music. So you get this whole eclectic feel within the gospel arena. There are just so many different beginnings to it.”

And, as it turns out, there are happy endings as well. While church bands can foster talent in the making, they can also offer a haven to great players who once toured the world. Such was the scene I stumbled upon at the historic Mt. Pisgah Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Church in Orange Mound, which only last month celebrated its 139th anniversary. Attending their service on that Sunday was like turning the calendar back a half century. On either side of the 90-year-old building’s proscenium, high above the altar, were two vintage Leslie speakers, hard-wired to a classic Hammond organ. At the keyboard sat Winston Stewart, longtime member of the Bar-Kays throughout their ’70s and ’80s heyday. Playing bass behind him was Barry Campbell, who was in demand as a New York session player for nearly 20 years, playing with the likes of Eric Clapton, David Bowie, and Quincy Jones. Together with drummer and singer Austin Bradley, guitarist John Black, pianist Davida Winfrey, and the earnest choir led by City Councilwoman Jamita Swearengen, they created magic.

As one friend noted, finding such talent in unassuming corners of the community is as Memphis as it gets. And it helped me appreciate the phenomenon of the church band as a haven as well as a hothouse for youth. As Campbell tells me, “When I was in New York, the music industry began to change. Everyone went for that MIDI programming thing, like with hip-hop and rap. And the rent in New York City kept going up. After a while I was like, ‘Why am I here?'”

So he returned to the community where he grew up. “It’s a church in the ‘hood,” he says. “It’s old-school. It’s a good church. Young people want that contemporary stuff, those mega churches with flat screens and big sound systems. But musically, at Mt. Pisgah we’re still kinda doing it the way they did it back in the ’60s and ’70s. We’re not really throwing in much of the jazz fusion that’s going on now. We’re more soul and blues-oriented. We don’t get into too much Kirk Franklin-type stuff because we don’t have a youth choir. Everybody in the choir is old enough to be my big brother or daddy or mama.”

Neither Campbell nor Stewart grew up playing in the church but came to it later in life. For Campbell, this was partly a practical matter. “Live music isn’t as popular as it once was. So a lot of musicians have gone to the church over the last 30 years. Once I came back, all my guys had a church gig. Every church had at least a bass drum and keyboard. Some churches even had synthesizers. Some had bands. I even knew white churches that had orchestras. It just expanded to where it’s a thing now.”

On this late autumn Sunday, I was glad it was a thing, as Winston Stewart coaxed waves of emotion from the Hammond organ in a minor key, playing even the drawbars’ shades of timbre deftly, while the bass and drums defined a slinky pocket. Though Stewart’s a relative newcomer to the gospel idiom, it was clear that his lifetime of music and soul was pouring out of those speakers, as one extended organ showcase piece after another evoked waves of blues-drenched sorrow and joy.

It was then that the Reverend Willie Ward stepped up and quoted Romans 10:17. “Faith cometh by hearing!” he declared. Still recovering from the reverberating wooden chambers of the organ, bass, drums, and guitar, topped with those soaring voices, I was inclined to believe it.

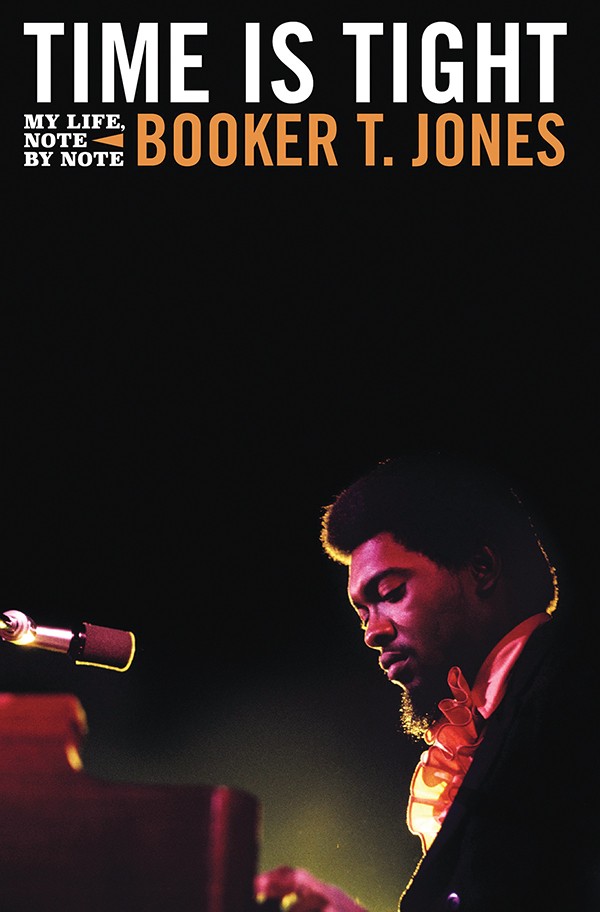

Most Memphians associate Booker T. Jones with the M.G.’s, the house band for the glory years of Stax Records and instrumental hitmakers in their own right. But Jones’ several decades’ worth of hits as a producer and distinguished sideman after moving to California should not be lost in the shuffled beats of McLemore Avenue.

This quickly becomes apparent when reading his vivid and thoughtful autobiography, Time Is Tight: My Life Note by Note (Little, Brown, 2019), which opens not on the tracking room floor of a studio, but with the words “Acapulco Gold,” the smoke of a joint wafting around him during his first brush with an earthquake in Malibu. From there, Jones presents vignettes from all chapters of his life, skipping like a stone over the river of his years. And, of course, many ripples extend outward from Memphis.

Piper Ferguson

Piper Ferguson

Booker T. Jones

Still living in California, Jones spoke with me about how he came to write the book, his approach to music, and how he still treasures lessons he learned in the Bluff City long ago.

Memphis Flyer: Was your new book quite a long time in the making?

Booker T. Jones: Yeah, it was much longer than I thought it would be. I didn’t start out to write a book. Ten or 12 years ago, I was just writing some essays about my life. It was almost like practicing songwriting. I was just practicing writing. And my wife said, “Why don’t you make that into a book?”

I had a number of accomplished authors offer to write or help me write it. But I read some autobiographies of some very close friends, and the problem was, all the events were accurate, and the facts were accurate, but the voice was just not their voice. So that’s why I decided I’d just like to, right or wrong, do it in my own voice.

Your voice certainly comes through in the very personal passages, such as when a teacher caught you cheating on a test and took you straight to your father’s classroom in the same school.

Yes, and in the book, there’s a photo of him in his white shirt and tie, standing by his blackboard. And that’s right where the woman marched me, right up there in the front of the room, right next to him. That’s where I had to stand in front of everybody.

Reading the book, one thing that strikes me is the importance of families to the Memphis scene. The Steinbergs, the Newborns, the Jacksons, and your own.

I’m glad you picked that up. It’s amazing, how there’re a lot of indications of that. It’s in the language. The use of words. And a lot of it is in the nice sense of community, of well-meaning activities for young people in Memphis that I took advantage of.

I’m curious about your approach to minimalism, your restraint, through so much of the Stax material. You never really tried to play like, say, a Jimmy Smith.

It was a convergence of attitudes, fortunately, for me, when I got to Stax. It was always underneath the surface, but it came out into the open with Al Jackson Jr., and Duck [Dunn] and Steve [Cropper] in particular, and also Jim Stewart. We actually talked about it. We didn’t use the term minimalism, but it was almost like, “Keep it simple, don’t play too much.” It’s almost like there’s a spiritual revelation or accomplishment in simplicity.

We’re really getting into it here, Alex, with this whole idea behind minimalism and music. I mentioned in the book that when I was playing the song “Time is Tight,” I hold that note, that one G, for so long in the melody, but that also gives me a chance to kind of emote and be emotional while that note is playing, you know, underneath it. And it’s such a simple melody.

You work the Leslie [tremolo speaker] beautifully on that simple melody as well.

Thank you. I’m really glad to hear you say that. I wanted this to be a book for musicians, to relate to and get into some of the concepts, and do exactly what you’re doing with it.

Yes, you even have some musical charts in the back.

The music that is printed in the book represents ideas of mine that go with the chapters, that I’m trying to emulate some of the feelings of those chapters. It’s not really music that’s been recorded. It’s just three or four bars of sentiment about that particular chapter, in music.

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Courtesy of Stax Museum

Booker T. Jones

Speaking of the power of simplicity, I was fascinated to read that you were inspired by Bach when you composed “Green Onions.”

It’s just those three chords, the one, the minor three and the four, and the inversion on the right hand, where the little pinky finger starts on the tonic and goes down to the fifth and then the third. And it’s the repetition of it. I feel like the voicing I’m using is Bach’s piano voicing. And that’s what I was studying at the time. I was trying to figure out Bach’s reasoning for moving the notes the way he did when he wrote all his contrapuntal fugues and so forth. And repeating all that over and over in a kind of jazzy, bluesy, groove, there’s just something about the imposing that on blues. I don’t know how to say it. There’s something about that. It’s still one of my favorite records. It still kind of hypnotizes me.

You might be interested to know that there’s a crack band of Memphis players, the MD’s, who play only Booker T. & the MGs music. And they’ve just launched a project based on imagining “what if the MG’s interpreted the Beatles’ Revolver just as they did Abbey Road?” In fact, the band learned the entire MG’s album, McLemore Avenue, before they did it. It’s really something. They call the new album Revolve-Her.

I’d love to hear that. Revolve-Her! That’s reminiscent of Hip Hug-Her! Well, they are really into it.. Cool. That’s so great. Send me whatever information you can. If they worked on McLemore Avenue, that would give them a jumping off point for how to do that, how to have a better understanding of doing Beatles music in the spirit of Booker T. and the MGs.

Reading the book, I was impressed at how deeply you studied music theory even at Booker T. Washington High School, and then later at the University of Indiana at Bloomington. Was there a conflict between your love of minimalism and the formal studies of complex music theory and arranging you were doing at BTW and Bloomington?

It was impossible for it to be a conflict for me, because so early on I had this curiosity about the different instruments and their textures. So I was compelled to know what key the French horn is in. What an F-clef was. I had the music in my head, and that was what I wanted to write down. So I never did get the chance to choose to be a by-ear musician. I knew a lot of people who were, and I could have been a by-ear musician.

Although actually, I was a by-ear musician. And I think I fooled a lot of people, because I could hear music and I could play it just ‘cos I heard it. A lot of by-ear musicians do that; they can play symphonies or whatever, without actually knowing what the notes are. But the minute you get that desire to reproduce for a group like the Memphis Symphony…

Anyway, I still do by-ear sessions. I just did one a couple weeks ago. I don’t always write it down. I think I function both ways, now that you mention it. I never really thought about this before. A lot of players, you can just hum it to them, and you say, “Put a harmony to this,” and they know what you mean. And in some ways it’s faster.

You know, we did head arrangements at Stax. But those guys also read music. So sometimes I wrote stuff down for them, but most of the time, we worked with artists who just hummed the lines to us, or just did our own head arrangements.

Otis would dictate horn parts…

Oh yeah, he would jump around singing and shouting and humming.

Did he suggest organ parts that way?

No, usually horns. He had song ideas, and definite ideas about horns. He left the keys pretty much open to me and Isaac.

I was shocked to read that that’s Isaac Hayes playing organ on “Boot-Leg.”

I was shocked too! I drove 400 miles from Bloomington to Memphis, and Cropper says, “Hey Book, I want you to hear something.” He played “Boot-Leg” and I was so confused. I thought, well maybe that’s a Mar-Keys record, when I heard the Hammond organ. But I don’t tune the Hammond that way; I have different drawbar settings. Yeah.

Well, you were gracious about it.

Thank you. It’s great, it’s absolutely a great track. Great bassline. I love it.

Were there any other MGs tracks that didn’t include Booker T?

That was the only one, while it was Booker T and the MGs. It was the MG’s without me, I think Carson Whitsett played with Al and Duck and Steve after I left Memphis. But “Boot-Leg” was the only one. It was a great one though.

Booker T. Jones

People don’t talk about your piano playing much, but it seems that’s as much your instrument as the organ.

Yeah, I am first and foremost a pianist. I do Hanon scales maybe twice a week or more. That’s my go-to when I want to whip myself into shape. The first time that music evoked an emotion in me was hearing my mother play Debussy, Liszt, and Chopin on the piano. Very emotional stuff.

You write in the book that scoring the movie Uptight! was fulfilling a long held dream of yours, to compose soundtracks. But I gather you didn’t do many soundtracks after that.

No, that’s true. I had dreamt of going to Hollywood and scoring movies at some point. I think that’s one of the reasons I went to Indiana. Of course, when I got to Hollywood there were no African-American musicians scoring music. Henry Mancini was trying to bring people like Quincy Jones in and Quincy was really the only one that kind of broke through that. Of course he came right to see me when he heard I was doing the score and sent aides over to my sister’s house, to help me.

So there was a lack of opportunity for black directors and composers as well. I was really disappointed in Hollywood in that area. Uptight! was a Jules Dassin film. Jules was very talented. But because of his political leanings, he was not a Hollywood favorite. I think he was pretty lucky to get that deal with Paramount. But he actually got kicked out of Hollywood because he was married to Melina Mercouri, and she went on the Johnny Carson show and told the nation that Greece was about to be overrun by a junta. So that happened, and the next morning we were up and out of Hollywood, just like that. Just gone, out of Hollywood. So we went to Paris.

But yeah, scoring films was an ambition of mine. I guess I used to go to the theater on Mississippi Boulevard and that was a fantasy of mine.

It seems things have changed now enough to where you could have more opportunities now.

The industry has kind of moved on. It’s completely changed. But it’s a hard job to score a film. It’s a lot of work. I know quality musicians that have left the field because it was so crazy. André Previn was the first one. He was making millions of dollars composing music and he quit because it was just too much. The deadlines. You work with a director, and music has just such a big role in pictures, and it’s just so arbitrary, I’ll say that. You have to be so disciplined as a composer for film, because it’s all about the story. It’s all about what’s happening on screen.

You sometimes work with students at the Stax Music Academy on your return visits.

Yeah, so much talent there. I used Evvie McKinney on my recording of ‘”‘Cause I Love You.” She sounds so good on that song. She’s a Stax graduate, and I’m sure there’s gonna be collaborations with others from Stax in the future.

Time Is Tight: The Life and Times of Booker T. Jones

I just started a record company, that’s why I’m saying this. It’s called Edith Street Records. ‘”‘Cause I Love You” is the first release on Edith Street Records and it’s a companion to Note by Note album, which is a companion to the Time is Tight book.

What’s the rest of the new album like?

It’s a musical reproduction of my life. ‘”‘Cause I Love You” was the first song I ever played on at Stax. “Time is Tight” and some of those songs I recorded in Memphis are on there. And it kind of correlates with the chapters of the book. Each chapter has a musical song as its title.

You were relatively young when you moved out west. What does Memphis mean to you today?

Sometimes, when I’m preaching about how great it is to have come from Memphis and how lucky I was to have been born there, someone might say, “Well, I come from Cincinnati, and it’s great to be from there too!” But I do feel that Memphis is special, and I’m thankful that I grew up there and got my musical start there. And Time Is Tight is sort of a tribute to that, I think.

An Evening with Booker T. Jones, with Daily Memphian reporter Jared Boyd, takes place at the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, 926 McLemore Ave., Friday, November 1st, at 7 p.m.; doors open at 6 p.m. A screening of an Aretha Franklin documentary takes place at 4:30. Free.

On any given day, dozens of Memphis musicians are crisscrossing the country, bringing the diverse sounds of our city to audiences large and small. It’s a fun life, but things don’t always go as planned. It’s a tradition for musicians to swap stories of disaster, humiliation, and stiffed payments. Here are some prime cuts from Memphis musicians who were willing to go on the record about their worst gig experiences.

Dead Soldiers

Krista Wroten Combest — Dead Soldiers

We were on our way from Asbury Park to Brooklyn, and then to Staten Island. The guy at the toll booth told us the wheel on our trailer was smoking. This wasn’t surprising to us, because on our last tour, the wheel had fallen off as we were attempting to leave Sister Bay, Wisconsin.

That’s why we weren’t surprised when it happened again in New York. We pulled over and called a bunch of auto places, but no one was open, so we decided to take it easy and just get to the show. We limped into New York and somehow made it through the Staten Island tunnel, which is more than a little terrifying when you’re hauling a broken trailer behind a conversion van.

We finally made it to the venue and had a great time and got to party with a bunch of our Memphis transplant friends. Loading out after the show, Clay [Qualls] accidentally broke the key off in the lock on our trailer. It ended up being easier to just tear the trailer door off rather than deal with the locks and load all our stuff into the U-Haul we rented for the rest of the tour. All the while we were being harassed by a junkie who looked like an extra from The Nightmare Before Christmas. We had to make the tough choice to abandon our trailer there in the Big Apple. Another victim of the road. R.I.P. trailer, I hope you’ve finally found peace in some scenic New York junkyard — or as a Brooklyn hipster’s apartment.

Joey Killingsworth — Joecephus and the George Jonestown Massacre

I got so many bad stories…

We drive to the middle of Georgia to play a car show. And to get there, you had to get walkie-talkied in. One car at a time on this little gravel road in the middle of nowhere. Once you got down to it, there was a field with all of these cars and stage in front of a dirt track. We start talking to people, and these rednecks are scary even for white folks. Dave said, “You took me to a Klan rally where they don’t bother to wear hoods.” These motherfuckers were crazy. These guys were showing us their gun wounds, their knife wounds. I was like, this is a little too much for us.

There was a guy in a blue gorilla suit playing upright bass, doing ‘White Wedding”, and some ‘80s songs. He was cool. But then we got on stage, and the wind started blowing towards the stage. Whenever the cars would drive behind us, the dirt would blow up on us. It was covering my pedals, my guitar, everything.

As soon as we got done, we were like, we gotta get paid and get the hell outta here. But they were like, hang on, we have an emergency. Somebody broke their foot. We’re waiting on a helicopter. We were like, why don’t you just get the ambulance? No, he was some drunk redneck on a quad runner, and his foot actually broke off, like, it came off. So they had to airlift him out. And that was Dave Wade’s first show with us. He said, ‘That was the day I said, ‘I’m never going to do this again.’ That was six years ago.

My personal worst was the Hogrock festival in Illinois. It’s in the middle of a field that they used to use for the Gathering of the Juggalos. There are three big stages. You gotta follow trails in the middle of nowhere to get to them.

At first it was awesome, but it turned out that was the night the cicadas came out. Like, they were literally emerging from the ground. We were in an open area in the middle of the woods. Me and Brian [Costner] were not wearing shirts, and Daryl [Stephens] from Another Society was playing drums. The cicadas were swarming all over us. They stayed on us the whole time. They were swinging on the bill of my cap, hanging off of my guitar. It was like somebody throwing softballs at you. I would kick a bunch of ’em out of the way to get to a pedal. Daryl said he was just playing and cringing, watching these cicadas climb on our backs. We did an hour and a half set. It was like that the whole time.

Marco Pavé

Marco Pavé