A 40-or-so-minute drive will take you to the site where William Faulkner died some 60 years ago in Byhalia, Mississippi. It’s a gas station now, but in its place once stood the Leonard Wright Sanatorium, a reputable place but one stigmatized with its association for treating alcoholism. Perhaps, that is why when Faulkner died in 1962, the Memphis Press-Scimitar, The Commercial Appeal, and The New York Times reported that the author died in Oxford, his death shrouded in shame and unasked questions even today.

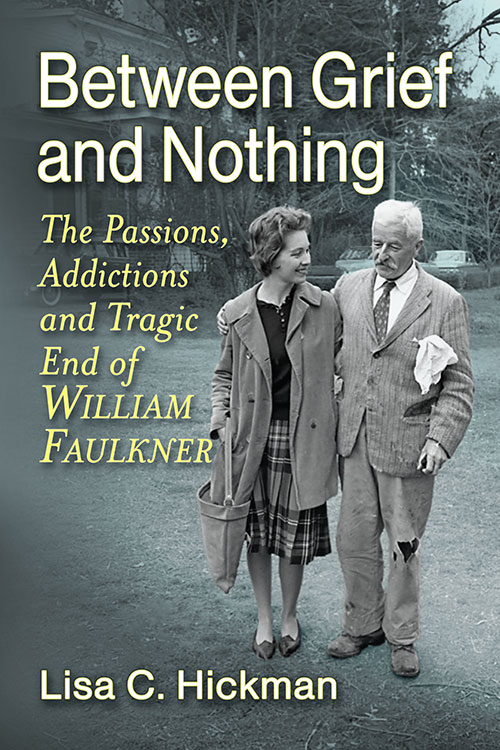

For her part, though, with her Between Grief and Nothing: The Passions, Addictions and Tragic End of William Faulkner (McFarland), author Lisa C. Hickman examines, in great detail, those final moments of Faulkner’s life and the context surrounding it — his emotional instability, mental health, various addictions, and a culture ill-prepared to address these issues.

Hickman has been fascinated with Faulkner since taking a single-author course on him as a sophomore in college. “Faulkner’s literature is always relevant because it’s a window into human nature,” she says. She later earned her Ph.D. at Ole Miss with a concentration in Faulkner and Southern literature. “Then, I met and became good friends with novelist Joan Williams, a Memphian who’d been in a relationship with Faulkner. That opened an entirely different window. His literature and personal life converged.”

Meeting Williams also led her to writing The Romance of Two Writers about the two writers’ affair, and through it, Hickman learned of Faulkner’s “rich interior world,” which she was able to delve into deeper in her most recent release. “These extramarital affairs he sought were another form of addiction, and aspects of them were more imagined than realized, yet they kept him going,” Hickman says. “His wife, Estelle, is fascinating. A brilliant, artistic woman who had her own struggles. She actually was a patient at Wright’s before her husband.”

“I’d actually walked around the site a couple of times, once with Joan Williams, so I was familiar with it,” she adds of Wright’s Sanatorium. “There were dilapidated, small scattered cabins. … The grounds were eerie, otherworldly. Two metal lawn chairs remained positioned side by side under a favorite oak tree. You couldn’t help but imagine the patients wandering around in various states of dishevelment. Honestly, it was a bit like a Stephen King novel. I was fortunate to interview some of the last close associates of the sanatorium, and the family who purchased the property were careful guardians, photographing what was left of the original structures and preserving the records, documents they discovered under a stairwell.”

Between Grief and Nothing includes these interviews and more, including previously undisclosed medical details. “Many of my sources are new and original — and hopefully reaching a readership outside of academia,” she says.

Hickman also says that readers don’t need to be familiar with Faulkner’s life or works to read her book. “I wrote this book with a general readership in mind focusing on a propulsive narrative. … There’s this collusion — between his genius and struggles — and while his creative powers aren’t widely shared, his struggles are widely relatable.”

“I often was stuck by the mindset toward alcohol and drug addiction during Faulkner’s time. Treatment was a band-aid until the next episode. While therapy has come a long way since then, we’re still living in a culture ripe with addictions.”

To celebrate the release of her Between Grief and Nothing, Novel will host a Meet the Author event with Hickman on Saturday, February 8th, at 2 p.m. You can order a signed copy here.