Robert R. Church and “Boss” Crump were once viewed as political allies. On the surface, they looked like oil and water, but, for years, they operated like a match made in heaven.

Or so it seemed.

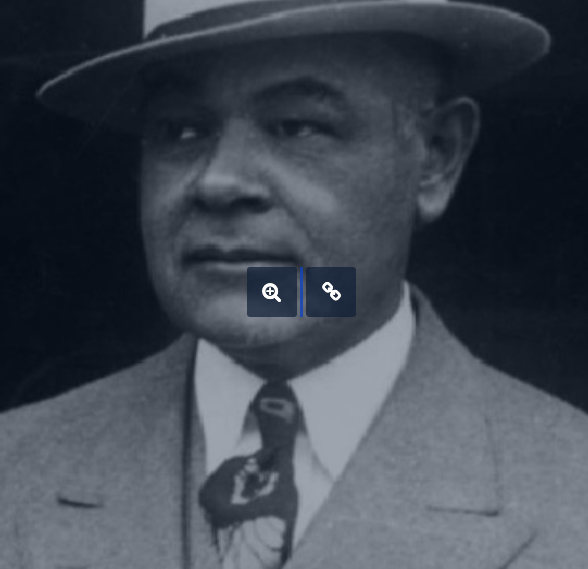

Robert R. Church

Church, a Republican, was the South’s first black millionaire. Mayor Crump, a white Dixiecrat, was a political provocateur who willed power over Memphis well through the 1940s.

Author Preston Lauterbach’s essay, “Memphis Burning,” describes how their “bipartisan, biracial coalition” ultimately “controlled Memphis politics and elected most of its officials.”

We see a similar longing for this perceived political utopia in the current electoral landscape. We see polished and seasoned politicians (and a few younger aspirants) angling allegiances with unlikely allies — black democratic congresspersons aligning with Republican Governor Bill Lee; black county commissioners and city council persons yielding to the likes of University of Memphis President David Rudd, FedEx CEO Fred Smith, major real estate moguls, and the like.

Wait. Something seems rather one-sided here.

Boss Crump

It seems that the reach across the aisle is only coming from one side.

In this framework, black political elitism is always hamstrung by an invisible hand of a white economic monopoly. Check the campaign pledges of the most notable elected officials and there we find commonality in donor-ship. This means that what most of us view as black exceptionalism is, actually, black tokenism — a few people of color who have proven themselves to be nonthreatening to the establishment and political status quo.

This tokenism has cultivated a generation of people aspiring for office who long more for assimilation than liberation. Too many black people aspire to (and obtain) positions of influence at the expenses of empowering the masses. They don’t want a more equitable society. They want to be in closer proximity to power. They want triumphalism — a better seat on the bus of injustice and inequity. And they will exploit social justice talking points to obtain it.

A bipartisan and biracial coalition might be possible, but there is no true partnership if only one side makes all the compromises.

If, for instance, white power brokers were sincere about equitable relationships, they’d be on the front lines advocating for equitable access and inclusion in the political process. However, when it comes time to increase voter turnout, “mum’s the word.”

What we are left with is a group of aspiring Robert R. Churches being contained by a group of 21st century Boss Crumps. This matrix is the source of black folks’ political apathy. We can point to the decades of black symbolic leadership that didn’t yield much fruit in our perpetually impoverished neighborhoods. And it is hard to point to progressive and productive leadership when out of 150 of the most populated cities in the country, Memphis was 136 in how well it is run, according to the website wallethub.com.

If we continue this path, we’ll end up like that deceptive dynasty between Church and Crump.

Lauterbach goes on to detail how “short-lived” that “period of biracial cooperation” was. He writes, “In the late 1930s, Boss Crump turned on his counterpart. In the span of a few years, the Democratic machine banished Bob Church, seized his property, broke the family fortune, and dismantled his Republican organization, crushing the most vital arm of black enfranchisement in the city.”

Doesn’t that sound familiar? Past is prologue.

Black political elitism is a myth in Memphis if there is no massive political movement of everyday people (that centers black citizens) to support it. And what the myth of black political elitism has done is bind up our political imagination prohibiting black people from seeing what is possible.

What is possible is the ushering in of a more just, progressive, and equitable class of leaders. A group that gleans the support of the elders and inspires the next generation to become more optimistic about their involvement. The municipal elections this October could very well hold the key to the black political independence of the next 25 years. It’s about time we recognize what Dr. Martin Luther King called, “The fierce urgency of now.”

Dr. Earle Fisher is the Senior Pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church and founder of #UPTheVote901.