The theme of the 2024 Oxford Film Festival is “Stories That Shape Us.” The annual festival runs from Thursday, Feb. 27 to Sunday, March 2, with screenings taking place at the Malco Oxford Commons Cinema in Oxford, MS.

“Mississippi has always been a place where stories flourish,” says Oxford Film Festival Board President Mike Mitchell. “From music to literature to film, our state is a cornerstone of storytelling. That’s why, this year, we’re thrilled to amplify the creative voices that are putting Mississippi’s stories on the global stage.”

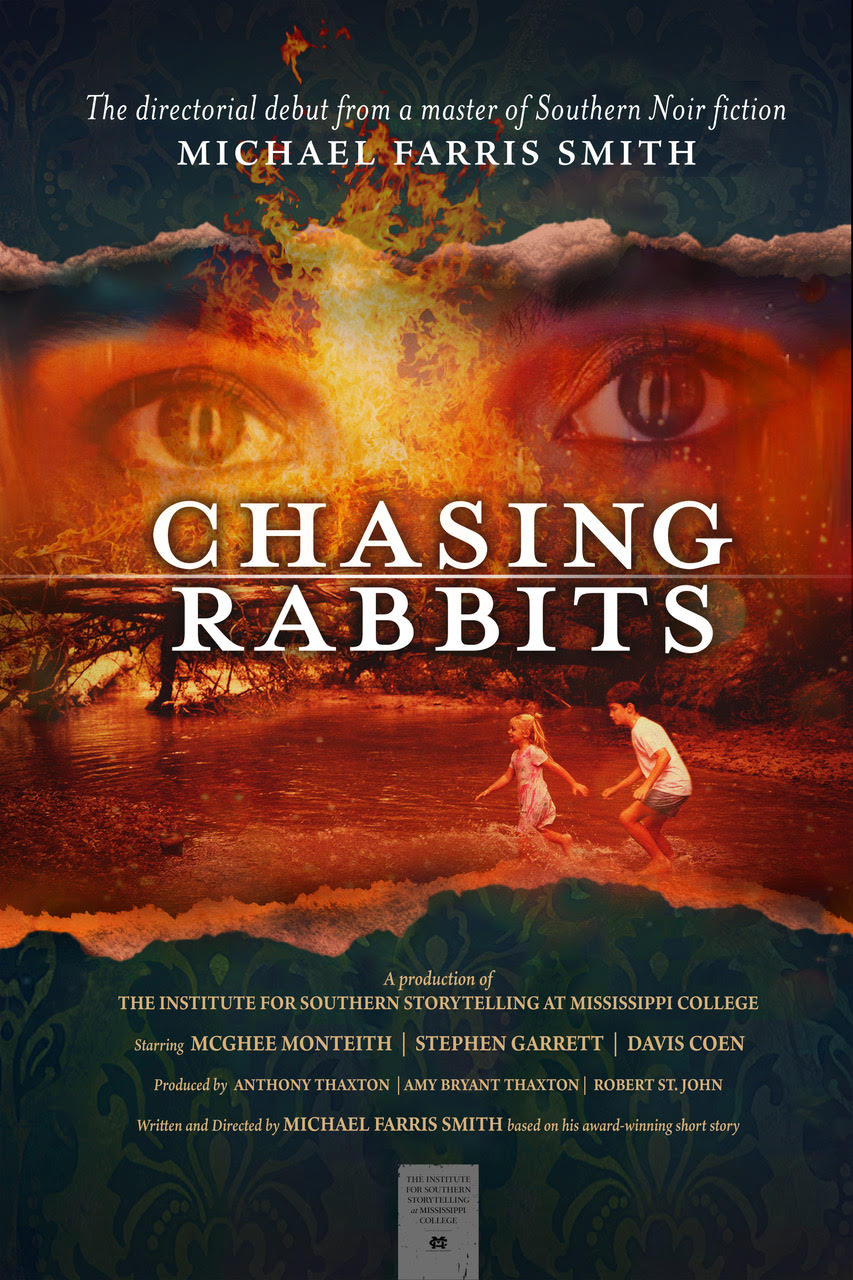

The opening night film is Chasing Rabbits, which is the directorial debut of novelist Michael Farris Smith. The McComb, Mississippi native has published seven novels, including Nick, a prequel to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby; and 2023’s Salvage This World, a sci fi novel set in the climate change-ravaged Gulf Coast of the future. Chasing Rabbits is a neo-noir film about a truck stop waitress who seeks revenge after her home is vandalized, and, in true noir fashion, things get out of control. 2017 Memphis Film Prize winner McGhee Monteith stars, along with Davis Coen and Stephen Garrett.

Opening the opening night program is “A House for My Mother.” Directors Pilar Tempane and Dr. Benjamin Nero. The short documentary traces the 88-year-old Dr. Nero’s life, from growing up in segregated Greenwood to becoming the first Black dentist from the University of Kentucky to his lifelong friendship with Morgan Freeman.

On Friday, the doc A Life In Blues: James “Super Chikan” Johnson gives the audience a big dose of the ol’ down home. Johnson is a Clarksdale, Mississippi native who is still slinging the blues at age 73. Vancouver-based filmmaker Mark Rankin and producer Brian Wilson bring the story to house rockin’ life.

On Saturday, March 1 is Stella Stevens: The Last Starlet. Andrew Stevens produced and directed this documentary about his mother, the Mississippi-born and Memphis-raised actress who stared in more than 50 films and television series, including Girls! Girls! Girls! opposite Elvis Presley. Stevens nearly 50 year career spanned the waning days of the studio system and the New Hollywood of the 1970s, appearing alongside everyone from John Cassavettes to Jerry Lewis.

After more than 60 films screen, the awards ceremony will be held on Saturday night. The winning films will receive encore screenings on Sunday.

For details about the entire program, individual tickets, and passes, visit the Ox-Film website.