Near the end of Godzilla, a CNN-like cable broadcaster describes the eponymous creature as “King of The Monsters — Savior of the City?” That question mark both highlights mankind’s ambivalence toward Godzilla’s status as its defender and champion and indirectly touches on Godzilla’s eternally evolving status in popular culture. Sixty years after his debut, what has changed? What kind of inhuman hero do we deserve now?

Answering this question is tricky. Filmmakers who downplay or ignore the implicit campiness of a gigantic, fire-breathing lizard that scowls like Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven do so at their own peril. But some form of distancing and detachment seems unavoidable, because Godzilla is one of the few pop-culture icons whose dozens of sequels and reboots strive to be less dark than the source material.

Like George A. Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead, IshirŌ Honda’s 1954 Gojira is both a high-concept genre exercise and a kind of national primal-scream therapy session. Released less than a decade after the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki and less than a year after the infamous Castle Bravo nuclear test at Bikini Atoll, Gojira is a Japanese film about the horrors of nuclear war and the dangers of unregulated scientific research. While it is true that Godzilla’s first-ever onscreen appearance isn’t very scary — he peers over a hilltop in broad daylight like a nosy neighbor — Gojira‘s powerful undercurrents eventually surface. When Godzilla returns later in the film to attack Tokyo, which is fortified with military firepower and surrounded by an enormous, multi-storied electric fence, he reduces everything in his path to rubble and sets it ablaze with a shocking, indiscriminate fury that’s effective in part because it’s so impersonal. As flies to wanton boys are we to the Godzilla; he kills us for sport.

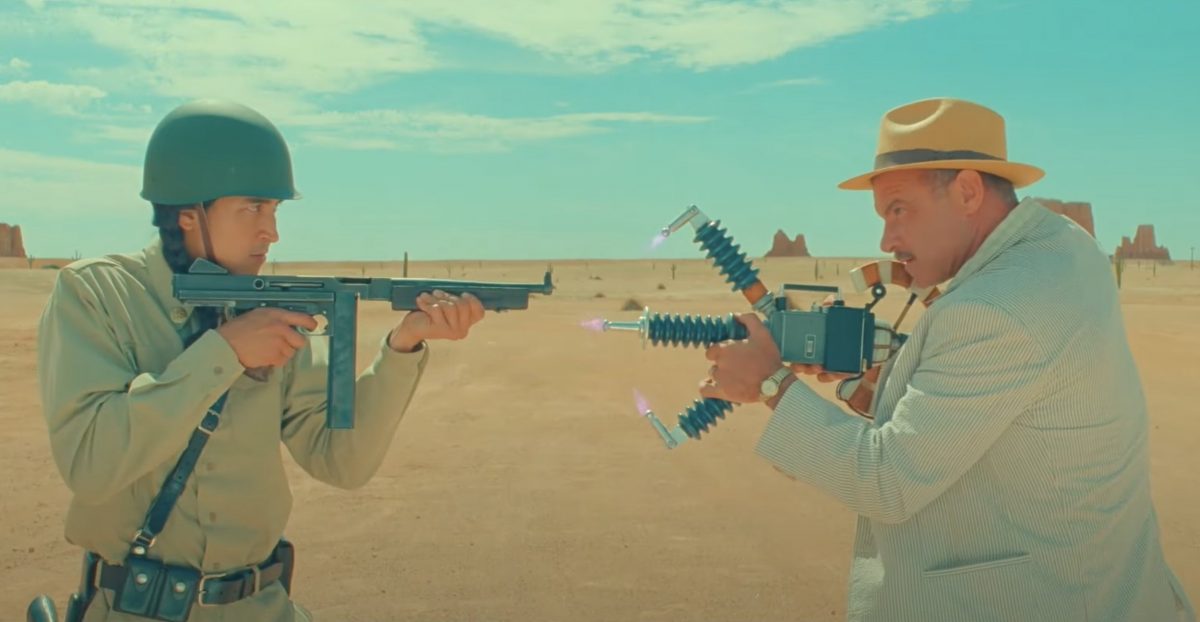

Bryan Cranston

Honda’s film unforgettably asserts that “humans are weak animals” whose grim fate is unavoidable. This is never more true than during the chilling scene where a widow crouches amid the flaming Tokyo rubble with her young children and comforts them by saying, “We’ll be with Daddy soon.” Gojira climaxes with an interspecies murder-suicide followed by a stern warning about environmental devastation from an aging, Lorax-like scientist. It’s clever enough to leave room for a sequel, but it’s downbeat enough to make people wonder whether they really want another sobering ecological nightmare.

Releasing a contemporary American blockbuster that condemns the impieties of progress as vigorously as Honda’s film is all but unthinkable. Yet the subtext is part of the Godzilla myth; ignoring it altogether causes just as many problems. If the filmmakers want to stage a simplified conflict between good monsters and bad ones, then Godzilla’s frightening independence and agency lose all meaning. This all-powerful creature shrinks and becomes a scaly, prehistoric Rin Tin Tin that answers the bell for mankind whenever Mothra or King Ghidorah start poking around.

Elizabeth Olsen

With the 2014 Godzilla, director Gareth Edwards and his team of technicians seem aware of the traps and contradictions of the Godzilla mythology, and they split the difference between scary and silly better than you might expect. Their monster is a big, pear-shaped, angry old cuss whose status as an apex predator in a world of enormous, ornery super-beasts unintentionally works in mankind’s favor. But since Godzilla is not human, he feels no remorse for the buildings he topples and the hordes of screaming, terrified people he steps on. The destruction he leaves behind is the price we pay for security — a message relayed through an overhead shot of Godzilla swimming from Hawaii to the mainland while flanked by a pair of Naval battleships.

Edwards keeps his ill-tempered star hidden from view for as long as he can — a visual strategy as old as the classic horror and sci-fi movies he draws from. This secrecy is apparent during Godzilla‘s opening credits, which wed historical photographs of atomic bomb explosions to blocks of text that are quickly redacted as though they conveyed sensitive classified information. (However, the only full credit I got before it was blacked out was “Produced by the fire-breathing Thomas Tull,” which probably means that this is one of the movie’s only jokes.)

Off-screen sounds and blurry photos are parceled out sparingly, and the first appearance of something inhuman is actually a sly fake out: the huge, glowing curlicue emitting radioactive pulses in an abandoned Japanese city is actually a “Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Object” or MUTO, an enormous pointy-headed insectile thing that snacks on warheads and glides around like a leathery stealth bomber.

My favorite example of Edwards’ tendency to withhold what people most want to see occurs just before Godzilla’s big reveal, when the Army fires off a round of flares to see what’s causing all the commotion. The flares soar up into the sky, but they only reveal part of Godzilla’s hindquarters; the full sight of him is still too much to absorb at once.

Those twin senses of moderation and awe fuel the best stretches of the movie. Forget about its all-star cast of puny humans (Juliette Binoche, Ken Watanabe, Sally Hawkins, Bryan Cranston, Elizabeth Olsen, and others), who exist largely to fill in plot holes. Godzilla is about imagery, and its shadowy visual poetry excels whenever Edwards and company try to convey the world-flipping emotional impact of an average person coming face to face with something out of a prehistoric creation myth. There’s a great shot from the point of view of an indefatigable military man (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) who parachutes into San Francisco and passes by the expanse of Godzilla’s spiny backside before touching down. First, you hear his heavy breathing. Then, almost involuntarily, you start to share his breathlessness.

That moment of fearful excitement sustains you all the way through the final battle, which takes place under the kind of malevolent grey skies that portend the end of history. The monsters have some tricks up their sleeves, and the fight and its aftermath manage to evoke some real pathos. But when it’s all over, it will be hard to suppress a cheer, or a roar, of victory.