Three hours separate Bluff City and Music City on an I-40 straight shot Memphis drivers know all too well.

“Oh, Jackson is bigger than I remember! Look kids, the Tennessee River! Ha, Bucksnort! There’s the Batman Building!”

Any Memphian who has routinely made that drive will have at one point wished for (a Buc-ee’s, of course, but also) a rail line to connect the two cities. This is especially true for any Memphian who has ever boarded the City of New Orleans train for a hands-off-the-wheel trip to another city up or down the rails.

But those choo-choo wishes here fade into the same place as win-the-lottery daydreams. Passenger rail is for those East Coast types or some European travel show on PBS. This is Tennessee. We won’t even expand Medicaid to save lives, let alone build a statewide train set so the fancies can swan around like they’re Rick Steves. So, I-40 drivers’ dreams go poof, they sigh, turn off the cruise control, and wait to pass a Big G Express truck in the left lane.

But a few things have happened recently to give those rail dreams a flicker of hope.

In 2021, Congress passed President Joe Biden’s massive Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. It promised $1.2 trillion in transportation and infrastructure projects with $550 billion for new projects. That pot of money opened the Federal Railroad Administration’s (FRA) Corridor Identification and Development program. Flush with $1.8 billion, it will help cities and states pick new routes for intercity passenger rail service.

In 2022, the Tennessee General Assembly publicly but quietly directed a state-housed group of experts called the Tennessee Advisory Commission for Intergovernmental Relations (TACIR, pronounced TASS-err) to study the feasibility of passenger rail here.

The bipartisan bill was sponsored by the unlikely duo of Sen. Ken Yager, a Republican from the far-east corner of Tennessee (Bristol), and Rep. Antonio Parkinson, a Democrat from the far-west corner (Memphis). But they had one thing in common — rail could help their cities. For Yager, Bristol could connect to Virginia’s ever-growing rail system. Memphis could connect to Nashville and beyond, and all of it could bring in people and their money.

“I have all the faith and confidence that [TACIR is] going to bring us back something completely comprehensive, whether it shows that rail is feasible or not,” Parkinson said when he introduced the bill. “It might not even be feasible, but whatever alternatives are available for us, we just need something to connect all of our people and all the tourists that come into our state.”

But as Parkinson introduced the bill to just even study the idea, GOP members quickly questioned the cost of rail. Many thought the idea was a good one (if not at least a pretty one), and no one voted against the study. But some knew already the Feds would not pay for the lines, nor the equipment, nor the resources it would take to maintain it. Hawk mode, it seemed, was already engaged.

In March 2023, Chattanooga Mayor Tim Kelly announced on X that “it’s time to bring the Choo Choo back to Chattanooga! This week, I submitted an application for federal funds in partnership with [the mayors of Atlanta, Nashville, and Memphis] to begin planning for a new Amtrak route through our cities.”

It’s unclear just where in line that application is now. But if the project is picked, the cities will get $500,000 to earnestly study routes and crunch numbers.

While rail in Tennessee has seen a flurry of activity over the last couple of years, Parkinson said it could take up to 15 years for a new passenger train to leave a station here. TACIR said if the process gets started and leaders remain committed to it, a train line could be operational in a hasty seven years.

Rail action could likely see the floors of the Tennessee state House and Senate in its next session this winter. Parkinson added that any rail ideas would need buy-in, also, from the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) and Gov. Bill Lee’s office.

For now, lawmakers are likely mulling the TACIR study and, maybe, gauging where the political winds blow on it. Also for now, it still takes three hours of hands-on-the-wheel, going-the-speed-limit driving for an I-40 nonstop trip between Memphis and Nashville.

A Rail Assessment

Rail travel shriveled across the U.S. over the last few decades. While Tennessee was never famous for its great passenger systems, the state certainly had more lines than it does today.

For example, ever wonder why Nashville’s beautiful Union Station luxury hotel is called a “station,” sits on train tracks, but has no trains? Well, it used to. It was once a major stop on Amtrak’s Floridian line, a 1,400-mile route that ran from Chicago, through Nashville, to Miami. But Amtrak stopped the service in 1979.

So, what does Tennessee have now as far as real, people-moving rail service, not meant as nostalgia machines? Very little.

Amtrak stations at Memphis and Newbern to the north are the only two such stations in the state. It’s another sort of feather in West Tennessee’s cap. It seems glitzy, but ridership figures dull the story. Ridership was still below pre-pandemic levels last year when about 40,000 boarded the train here. That’s roughly 3 percent of the Memphis MSA population. That ridership figure is down from a recent high of about 72,000 in 2017, or about 6 percent of the population. The station was on a shortlist for closure with looming budget cuts in 2017, but it was saved with the stroke of a Congressional pen.

Amtrak’s only train running through Tennessee, the City of New Orleans, runs between Chicago and New Orleans. The route through Tennessee follows the Mississippi River along the western border of the state, making only two stops, one in Newbern (close to Dyersburg) and another in Memphis at Central Station on South Main Street. Memphis is the state’s busiest station. While ridership here may have ducked during and after the pandemic, numbers climbed through the aughts, growing 15 percent between 2010 and 2018.

Nashville’s WeGo Star (formerly known as the Music City Star) began operations in 2006 and remains the state’s lone commuter rail line. The train runs east from Downtown Nashville to nearby Lebanon with several stops along the way on a 32-mile line. It was heralded as a helping hand to remove some congestion from the city’s famously jammed interstates. Ridership figures there haven’t bounced back to pre-pandemic levels, either, down by about 67 percent in fiscal year 2022. A WPLN story in July said that number rose to 40 percent of pre-pandemic levels this year, and now about 400 people ride the WeGo Star each day.

Trolleys move people in Memphis, but mostly tourists. Even though they run regularly enough (and usually on time), when was the last time you heard someone talk about their commute to work and say, “You won’t believe what happened on the trolley this morning”? However, sharp-eyed Memphians may have glimpsed sleek, modern streetcars on the Madison Line last year. The Memphis Area Transit Authority (MATA) is testing the new cars that could, one day, regularly carry commuters. The rail trolley system here is the only one in the state.

That’s really it. Other Tennessee trains do carry passengers, but do so for pleasure’s sake, not efficiency. That is, unless you count Lookout Mountain workers taking the Incline Railway.

What’s Proposed

Parkinson said when he proposed a transportation study from TACIR, it wasn’t only about rail. It was about moving people across the state and beyond, and about economic opportunities.

“I wanted to keep it broad enough for us to look at everything — not just rail — but any alternatives,” he said. “I wanted to know what those alternatives were, whatever the future of transport is. And if not rail, then what’s the future of transportation so we can be on the front end of it?”

The legislation he sponsored wanted a top-to-bottom review of the idea. That review had to look at physical train tracks in Tennessee, show what an intercity rail network would look like, and find alternatives to rail that might get the same job done. Lawmakers also wanted to see what kinds of projects like these have been done over the last decade. They wanted to hear from three other states about their rail projects. They wanted to know about possible stakeholders, costs, ridership estimates, operations, equipment, and more.

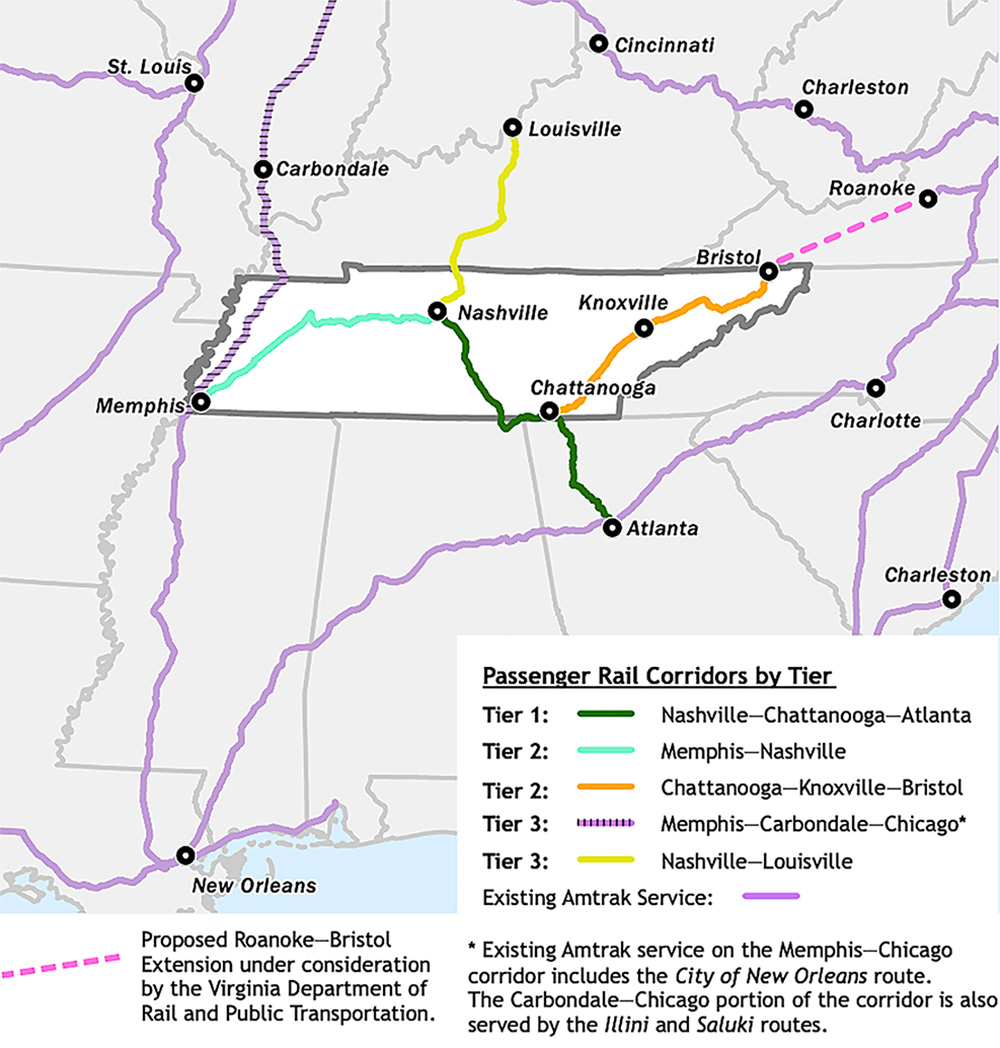

Two recommendations from the study made headlines when it was released in July. One, an intercity passenger rail system could “improve mobility and the state’s economy,” meaning it could work. Two, the group recommended five routes built in five phases.

The first would connect Nashville, Chattanooga, and Atlanta. To this, many Memphians likely sighed a unanimous “well, of course, Nashville ….” But the decision was based on moving the most people, connecting larger swathes of the country via rail, and existing infrastructure, like rail lines at airports in Chattanooga and Atlanta.

The next proposed route would connect Memphis and Nashville. The route was mentioned in 2020’s massive Southern Rail Plan from the Feds but was given a lower priority, though details on why were not given. That plan, however, saw the route as best suited as a link from the East to Midwest cities served by the City of New Orleans.

Well before TACIR recommended the Memphis-Nashville line, mayors of Memphis, Nashville, Atlanta, and Chattanooga had done one better and applied to the FRA’s Corridor ID Program. That application seeks to get rail done quickly with minimal investment.

Letters of support for the application flowed from every corner of every state involved right into the mailboxes of Pete Buttigieg, secretary of transportation, and Amit Bose, administrator of the FRA. Many of those letters refer to the proposed route as the Sunbelt-Atlantic Connector Corridor, even though that name does not yet even appear in any Google search.

“Each of our four cities are leading transportation and tourism hubs in their own right, and such a service would connect many millions of residents from beyond our municipal and state borders to reliable and frequent rail travel opportunities,” wrote Dennis Newman, executive vice president of strategy and planning for Amtrak.

Many of the letters read the same, including mentions of how the route could expand the economy and mobility, drive higher workforce participation and equity, advance “our international climate commitments,” and push tourism and leisure travel.

But letters from Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland and U.S. Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Memphis) mention one Memphis-specific need of the proposed route: BlueOval City. Work is underway now on the massive, Haywood County campus that will house Ford’s production line for its electric F-Series pickup trucks and batteries.

“The Memphis region will most benefit from the opportunity to help connect the 5,800 new workers needed to power the coming BlueOval City,” Strickland and Cohen wrote in their letters. “This mega-campus is envisioned to be a sustainable automotive manufacturing ecosystem. The $5.6 billion battery and vehicle manufacturing campus just outside of Memphis will be the largest in the Ford Motor Co. world.”

TDOT studied BlueOval City’s transportation needs, but only a passing mention of it made TACIR’s final report. TDOT aimed to figure out ways to move what it said could be between 5,800 to 7,000 employees from Memphis, Jackson, and nearby areas to the site, “and to try to avoid a surge in congestion along the I‐40 corridor.”

They came up with three ideas. Two of them are mixtures of buses and vanpools with start-up price tags ranging from $8.6 million to $14.6 million. Another option included a passenger rail system with a price tag between $490 million and $600 million. All of these transit options “would be used only by BlueOval workers,” according to TACIR documents.

While the 234-mile Memphis-Nashville route came in second, it does have a few things going for it, adding to its feasibility. For one, freight tracks already exist between the cities. Also, the TACIR study found lower freight volume between them, causing fewer supply-chain disruptions. The route is mostly flat, making it easier to build. While the population it would serve is smaller than the route to Atlanta, it would still connect a collective 3.4 million people in both cities and the roughly 171,000 folks who live in the 29 cities between them. Finally, other transportation infrastructure already exists in both cities.

Another Memphis route recommended by the TACIR study would enhance service from here to Chicago. Amtrak now runs this route once a day. But the study suggested connecting two other train routes — the Illini and Saluki routes — to increase daily frequency and mobility between the states.

The Money Barrier

Money will easily be the biggest barrier to making any Tennessee passenger rail dreams come true. They’re not cheap to build, they’re not cheap to run, and the state will likely have to pay for most, if not all, of it.

“The experience of other states suggests that costs can range from the hundreds of millions of dollars for more straightforward passenger rail projects to billions of dollars for more intensive projects,” reads the TACIR report. ”For example, Virginia estimates spending $4.1 billion on capital projects over 10 years.”

For costs to run a rail network, TACIR looked to North Carolina, another state making major investments in passenger rail. State-supported Amtrak routes there between 2015 and 2019 ranged from about $14 million to $17 million each year.

But as the study pointed out, Tennessee has, for years, committed millions upon millions of dollars, and staff, and other resources, to roads.

“As a result, [Tennessee] has a first-class road network,” the study said. “The experience of other states demonstrates that a similar approach can be used to overcome the barriers to establishing passenger rail.”

When asked about costs as a barrier, Parkinson was quick to say that, “operationally, they lose money.”

“But when you think about the indirect impact to the cities, to those towns, and those rural areas that are going to benefit from it, it would prove profitable from the rippling effect,” he said.

Others agree. The Southern Rail Plan said the Nashville-to-Atlanta route could produce a total economic output of $18.2 billion and support over 17,000 construction jobs. For travelers, the route could save $1.8 million every year.

Tennessee state numbers say 141 million tourists spent $29 billion here last year. Most of those originated from nearby states, all of which could be connected to Tennessee by rail. How could that impact tourism spending here? The closest analogue is a 2020 study from the Southern Rail Commission. It found that if rail brought even 1 percent more tourists to Alabama, it would generate an additional $11.8 million each year.

But For Now …

Where Tennessee will land on passenger rail is anyone’s guess. It will take a lot of time and cost a lot of money. That’s even if the idea gets off the ground, and getting there is promising to be a fist fight in the state capitol.

Now, however, most Memphians will do what we’ve always done: fill up the tank, buckle up, hit the gas, and, maybe, dream of a rail system one day. But we’ll definitely dream of a Buc-ee’s, preferably near Bucksnort.