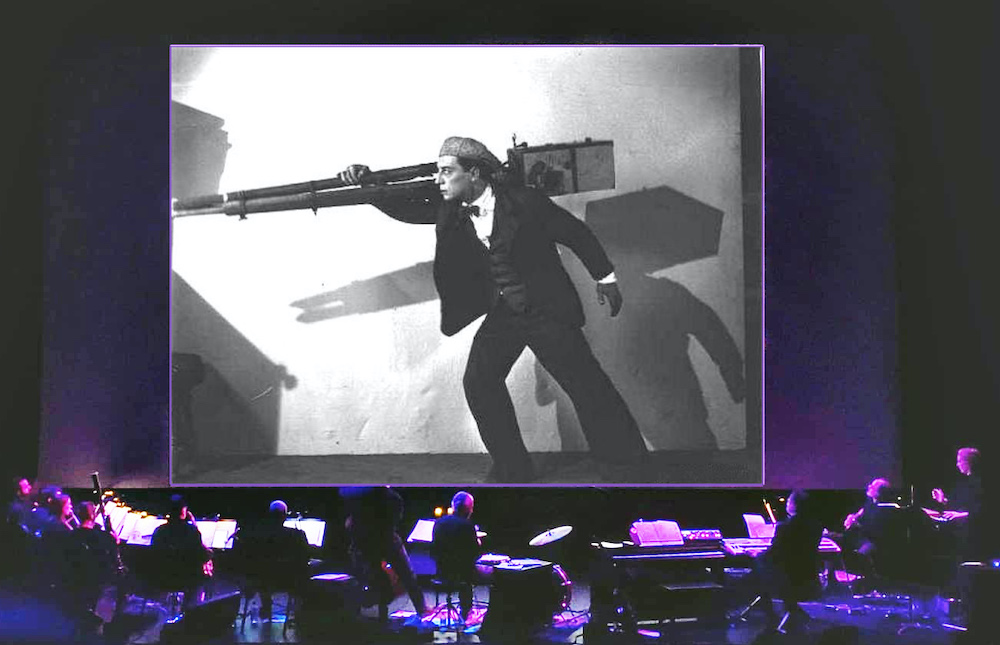

In January 2020, Alex Greene, joined by his jazz band The Rolling Head Orchestra and members of the Blueshift Ensemble, did something extraordinary: They performed original live scores to the silent films A Trip to the Moon and Aelita: Queen of Mars. Back in the first decades of the 20th century, people did it all the time, mostly organists in movie palaces, but occasionally with full ensembles. In the days before sound recording, some more elaborate film productions even came with their own sheet music for the score.

These days, it’s pretty rare, except for groups like the Alloy Orchestra, who have made a career out of performing live scores for films like Metropolis and Phantom of the Opera at film festivals. Just before the pandemic started, Crosstown Arts had commissioned a series of live scores in their new Crosstown Theater, where Greene was artist in residence at the time. “It was kind of the culmination of my residency at Crosstown Arts, and it was great, because they made everything very easy.”

“Very easy” is relative when you’re talking about writing original music for a 12-piece ensemble, including a theremin, that’s designed to sync up perfectly with a moving image. “It’s very different from recording a soundtrack,” says Greene. “You have the whole process of editing to make sure it all syncs up, but in this case, you’re just ‘Once more unto the breach!’ You’re launched into it and by the seat of your pants, hoping you can keep up with the movie, because there’s no pausing … I really wanted it to sync up with the emotional cues of the movie in a very precise way, as if you were watching a film with a pre-recorded soundtrack. That ambition made for a lot more work for all of us.”

Greene and the orchestra’s performance drew raves from the Crosstown audience, and the musician-turned-composer really wanted to jump into the breach again when COVID shut down the theater. He saw a new opportunity at Germantown Performing Arts Center’s new outdoor venue, The Grove, which features a massive video screen behind the stage. “I pitched to them back in January, and we went back and forth a lot about the best time to do it. At the time it seemed like summer was the best bet in terms of COVID, partly because the virus supposedly recedes in the heat somewhat, but also just we assumed once a vaccine became available everyone would be vaccinated by now. In any case, it is an outdoor venue, so even as early as January, we felt pretty safe in moving forward with a big concert like this.”

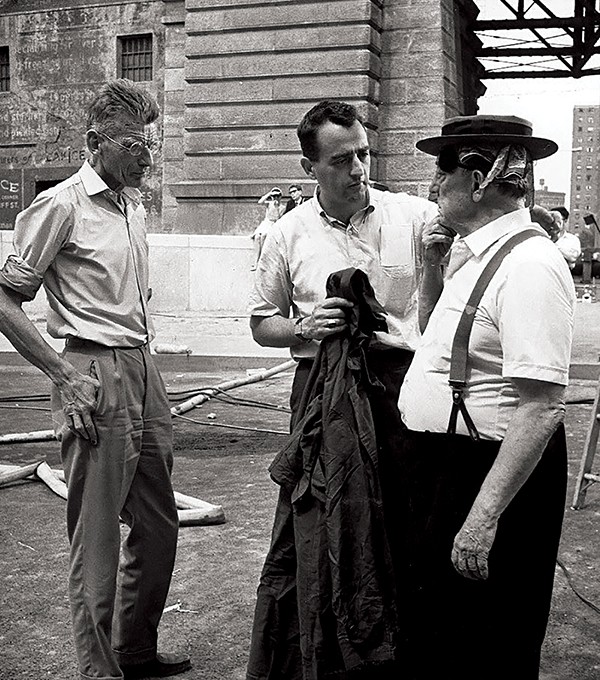

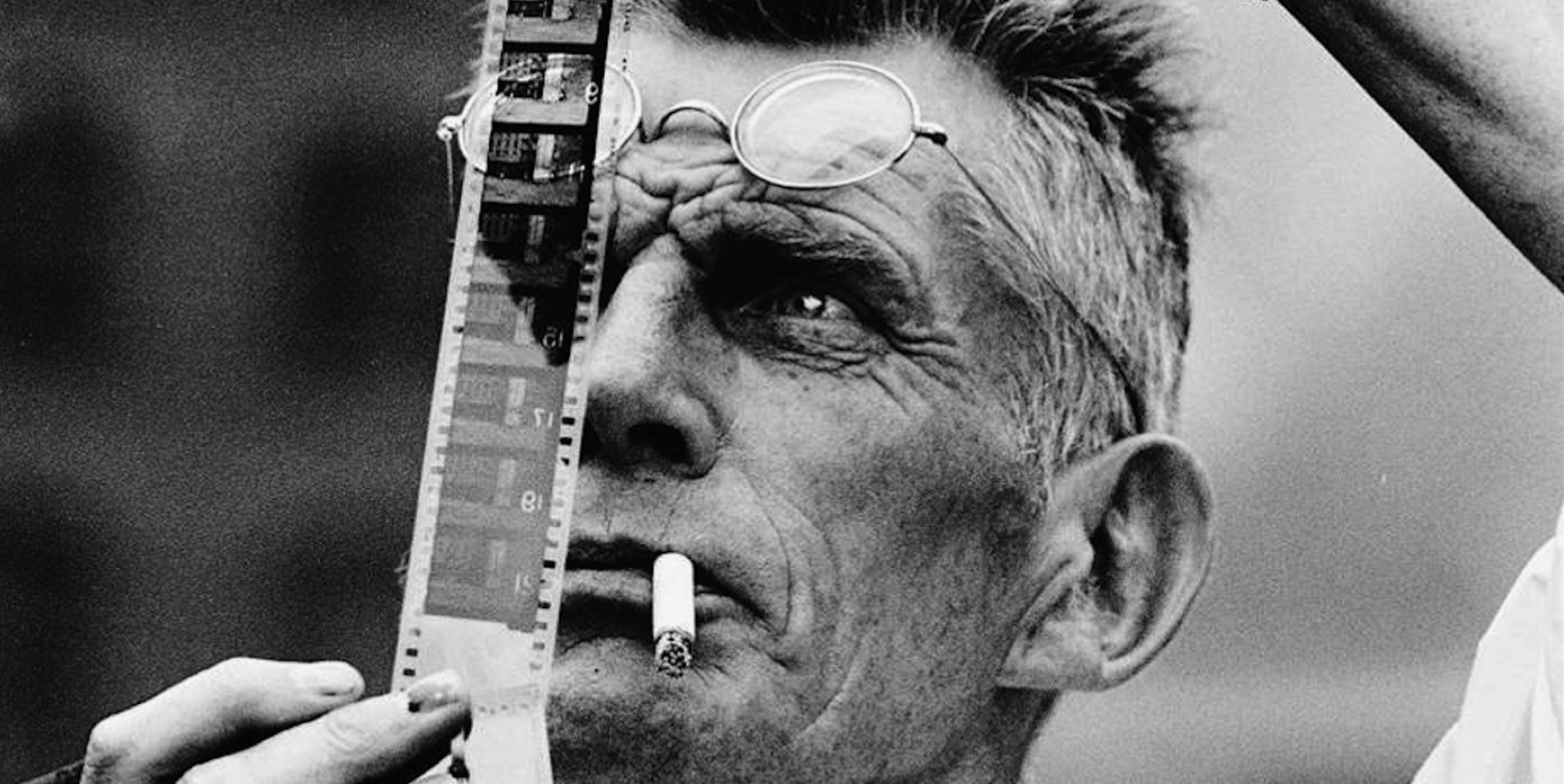

Greene says when it came time to choose a film, he wanted to “find something dark.” But GPAC director Paul Chandler disagreed. “People are emerging from a very dark year and a half, so let’s do something lighthearted,” Greene says. “I’ve always loved Buster Keaton, so I immediately saw what Buster Keaton films were being distributed by GPAC’s distributor, and the only one was The Cameraman, which I had never seen,” says Greene. “I looked it over and I loved it. I was like ‘Wow, why don’t more people know about this one?’ People know about The General, or Our Hospitality, or Steamboat Bill Jr., but this one is lesser-known, and in a way, that’s better for this kind of project. You’re seeing the film and the music in a very fresh way.”

The Cameraman is considered to be the last film of Keaton’s golden age, where he made incredible strides in big screen comedy and action in the mid-1920s. Keaton, who was used to total creative control, had just gotten a lucrative contract with MGM when he directed and starred in the comedy about a newsreel cameraman trying to impress a female co-worker — and failing spectacularly. It would be the last film Keaton fully controlled. Afterwards, MGM executives clamped down on the auteur’s perceived excesses; later, Keaton would say signing with MGM was the biggest mistake he ever made.

Green wrote the new score for the same band who played in January 2020: Carl Caspersen on bass, Mark Franklin on trumpet, Tom Lonardo on drums, Jim Spake on reed instruments, John Whittemore on pedal steel, and Jenny Davis and Delara Hashemi of the Blueshift Ensemble on flute, Jonathan Kirkscey on cello, Jessica Munson on violin, and Susanna Whitney on bassoon. “Once again, I have this wonderful theremin player from Florence, Alabama, Kate Tayler Hunt, who used to be the concertmaster at the Shoals Symphony. An injury prevented her from continuing as a violinist, so she pivoted and put all her conservatory training into the theremin. She has a very precise ear, and unlike a lot of people who play theremin for texture or sound effects, she can play melodies very accurately, and that just takes it to a whole other level.”

But before the players can bring the magic to The Grove, Greene has to write it down. “I’m scoring as we speak!” he says. “It’s really incredible, it’s a new thing to me. I started doing it in earnest with last year’s live score. Sure, I would write chord changes and lead sheets for my jazz group, but to actually score every note that everyone plays in a 12-piece group, and then to hear them execute it almost perfectly in the first rehearsal … it’s breathtaking!”

The audience will get to see Alex Greene and the Rolling Head Orchestra with the Blueshift Ensemble and Kate Tayler Hunt’s live score of Buster Keaton’s The Cameraman at The Grove at GPAC on Saturday, July 10 at 7:30 p.m. Greene says he hopes there are many other opportunities in the future to breathe new life into silent classics.