The Memphis Symphony Orchestra (MSO) took to the stage twice last week to play Brahms’ German Requiem. When you’re driving over a fiscal cliff, there are probably worse choices for a soundtrack. After years of economic uncertainty, the MSO has finally hit rock bottom, having spent all the money in its reserves. The crisis was made public at the end of January in a press release announcing that the organization was “taking steps” to complete its season and develop a “sustainable business model for the future.”

The MSO’s new President and CEO Roland Valliere doesn’t know what that new model will look like yet. He says his first priority is to meet current obligations to both orchestra musicians and the community and to end this current season “with grace.”

“The house is really on fire,” says former MSO clarinetist and current Board Chair Gayle Rose.

Comments made by MSO flute and piccolo player Chris James are in accord with Rose’s sense of urgency. James, who currently serves as the chair of the orchestra musicians’ committee, describes the situation as “a really big mess.”

“Assumptions about this year’s budget were soft, and we saw a cash-flow shortage on the horizon,” Rose says. “We can’t even start being creative and thinking about a new model until we address this.”

So when exactly did the bottom fall out, and what happened to the $6 million endowment the symphony established as a safety net in the 1990s? And how could an endowment created to provide the MSO with some degree of economic stability have been depleted to the point of sudden crisis?

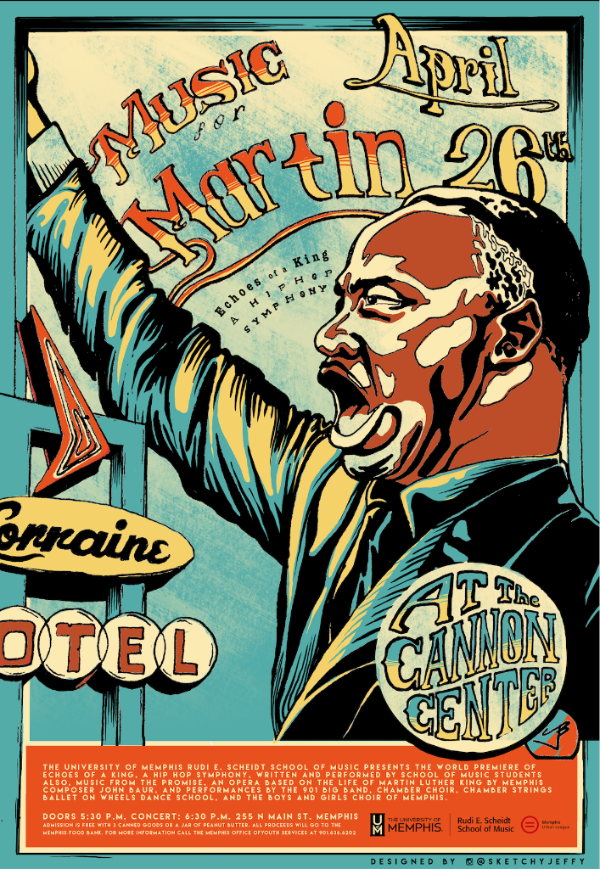

Rose says there’s no mystery. She knew the endowment was gone in July 2012 when she joined the MSO to raise emergency funds: “There was no surprise in terms of something suddenly disappearing and nobody knowing about it.” In a brief but candid interview, Rose describes years of deficit spending and traces the roots of today’s crisis back to a prolonged period of rootlessness between the 1999 demolition of Ellis Auditorium and the 2003 opening of the Cannon Center.

“Concerts were held in a church on Poplar,” she says, beginning a litany of little ups and big downs — describing a death of 1,000 cuts. “We lost subscribers. We lost growth in the annual fund. But hope springs eternal. The Cannon Center came online, and we were so lucky. Then in 2008 the economy crashes and we lose 40 percent of our endowment. Then in 2010 we get the energy of [new conductor] Mei-Ann Chen.”

James elaborates: “Overly optimistic board members, with nothing but good intentions, decided to prioritize artistic content over balancing the budget. I guess they thought if we produced good enough content, then people would give more money and buy more tickets.” The plan showed some early promise, but the orchestra was digging itself out of a big hole.

Rose doesn’t believe the impact of 2008 can be overestimated. “That’s 40 percent of what was already a declining balance,” she says. “The board saw what happened and tried to compensate by raising more money in the annual fund. But there’s only so much you can do to compensate for the loss of your safety net.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

The bad news is only magnified by elevated levels of innovation, audience engagement, and artistic achievement that have put the innovative “Memphis model” in a spotlight as orchestras across the country wrestle with similar problems.

In 2009, the MSO gained prominence when, in the absence of a music director, the artistic and administrative leadership joined forces in unprecedented ways. Believing that the fate of modern orchestras has less to do with classical music than the bond of reciprocity that exists between the musicians and the community they serve, the MSO launched several musician-driven initiatives. The “Leading From Every Chair” program connected orchestra musicians with members of the business community. The popular Opus One concert series attracted non-traditional audiences by pairing MSO players with regional rock, soul, rap, jazz, and world music performers, including Lucero, Amy LaVere, Al Kapone, and Jody Stephens of Big Star. In 2012-13, the MSO also partnered with Community LIFT to support community revitalization in the Soulsville area and play a series of free neighborhood concerts.

James is at a loss to list all of the musician-inspired startups that have been rolled out in the past three years. “We have a violist who works with the Autism Society,” he says. “A French horn player started a program with the Boys & Girls Club. Another violinist is working with a local actor for a women’s prison project.

James allows that not every musician was cut out for community engagement, and he also remembers 2009 — the year of attention-grabbing innovation — as the year Memphis musicians took a 10 percent cut in pay.

Opt-in projects like Opus One and “Leading From Every Chair” were created, in part, to make up for lost income. James describes the grants that helped bring these programs into existence and give the musicians employment opportunities, as “seed money only.”

“When Mei-Ann Chen arrived, we poured our guts into marketing her,” James says. “That’s the year revenues started to line up with expenses.” It’s an accurate description. The MSO ended fiscal year 2010 in the black, taking in $4,722,614 and spending only $4,610,653.

“All the leading indicators looked like we were going to come back,” Rose says, recalling the excitement surrounding Chen’s arrival. “The question was, did we have enough runway?”

The short answer to Rose’s question is: No. The slightly longer answer is: No, but maybe the orchestra can restructure enough to buy time and build a longer runway.

The MSO’s money and runway problems aren’t new. “The Memphis Symphony has not yet achieved long-term financial stability,” former MSO CEO Ryan Fleur said in a 2011 interview with polyphonic.org, the online forum for orchestra musicians.

“We’ve captured the imagination and attention of a much wider circle of Memphians who will ultimately help us change our own business model,” said Fleur. “Now we’re in lag time; in the business world it takes five years before you find the full revenue return on an investment.”

A lot of things have changed in the three years since Fleur proposed his five-year plan. Today, he’s an executive vice president with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Former MSO COO Lisa Dixon is executive director of the Portland Symphony. Innovative concert-master Susanna Perry Gilmore has joined the Omaha Symphony.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Fleur was contacted and asked to contribute to this story, but he chose not to comment on his time in Memphis. “I must defer to Roland’s and Gayle’s judgment on the best step forward right now for the Memphis Symphony,” Fleur wrote in an email. “I trust them to lead the way.”

“Let’s look at this on a macro level,” Valliere says, summing up the problem as he sees it. “In the business model of symphony orchestras there are basically three income streams. There’s earned income, which is what you take in from tickets and contract fees. There’s contributed income from a variety of donors: individuals, organizations, associations, the government, the National Endowment for the Arts, and so forth. The third stream would be income from investments, primarily from an endowment. … Over quite a period of time there was a structural shortfall, and for many years that needed to be covered. One of the ways was spending from the corpus of the endowment.

“When you look at business model, if you don’t have an endowment, you don’t have that 4 percent or 5 percent to draw from to help cover the budget. And that puts more pressure on the other two areas. So aligning things is a difficult task. Without a sea change gift or gifts adding up to a substantial infusion of capital, honestly, there is no painless way to do it.”

The dollar amount Valliere has attached to the word “substantial” is substantial; he says $25 million would reestablish the endowment.

John Sprott of Local 71-American Federation of Musicians hasn’t seen any proposals, but expects that MSO musicians will once again be asked to tighten their belts. “They need to find a way to balance the budget; usually that entails doing it on the backs of the musicians,” he says, acknowledging that there have already been administrative staff cuts. Although nobody knows what kind of pay cuts are ultimately on the horizon, the rumored number is a hefty 33 percent.

“The musicians are the symphony and a gift to this community,” Valliere says. “We need to appreciate any sacrifices going forward. They don’t make very much to begin with. But the financial reality is what it is.”

Financial realities are only part of the puzzle Valliere and Rose have to solve. As Rose has mentioned in other crisis-related interviews, classical music lovers can now sit down to their computers and pull up a performance by top drawer European companies like the Berlin Symphony Orchestra. Beyond its website and a basic social media presence, the MSO barely exists on the Internet. Other than a scant handful of Opus One fan videos uploaded to YouTube, there is almost no evidence of the ensemble’s live performances.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

In a recent keynote address to the League of American Orchestras, Elizabeth Scott, the chief media and digital officer for Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, allowed that, “There’s some truth to this notion that the way up will be tied to digital innovation.”

“The Internet is a sticky wicket because it goes out into the entire world,” Sprott says, explaining why provisions that allow orchestras to pay a reduced union rate to press a limited number of locally-distributed concert recordings don’t apply to the more streamlined digital download.

A new integrated media agreement (IMA) has been in place nationally since 2009, but it hasn’t been adopted in Memphis. It gives unionized orchestras better access to 21st-century tools for marketing and moving their products. The IMA allows limited video streaming on an orchestra’s own website. News stations can also run a promotional clip for up to 21 days on their websites, and provisions have been developed to cover popular content sharing sites like YouTube and Facebook.

Rose stresses that the MSO can’t continue to get by on contributed revenue alone. “This is where Roland and his entrepreneurial spirit kicks in,” she says, suggesting that there may be something other than more austerity in the orchestra’s future. But what?

Valliere has tried his hand at digital innovation in the past, taken big risks, and gotten mixed reviews. His first attempt to harness wireless technologies was called the Concert Companion, a visual orchestral counterpart to a museum’s audio tour. The Concert Companion — “Coco” for short — provided users with technical information about the music while it is played. Valliere developed the concept while serving as the concert director for the Kansas City Symphony.

In a blog post for polyphonic.org, MSO violinist Michael Barar publicly asked what it means to be connected to a symphony in crisis.

“Telling potential funders that you are nearly out of money is a double-edged sword,” he wrote. “Ideally, angel donors show up and the community rallies around an institution that it cannot imagine losing. However, an organization in as deep a crisis as the Memphis Symphony has probably been in trouble for some time, and has already tried to approach potential angels, and those angels may become weary of hearing the same cries of woe over and over again. After all, why should they continue to throw good money after bad?”

Rose validates Barar’s concerns. “As you can imagine, there are a limited number of funding sources in Memphis, and we all know who they are,” she says. “They’ve been on the receiving end of the Memphis Symphony story for a lot of years now. And yes, I think there is some fatigue there.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

There were only a handful of empty seats scattered throughout the house before the MSO’s moving February 23rd performance of Brahms’ German Requiem at GPAC. There had been more vacancies at the Cannon Center the night before, but most of the seats had sold and were occupied by mature, somber-faced patrons who clearly knew things were bad, and probably wondered how the crisis might affect performances. Even before the orchestra’s acclaimed conductor, Chen, took to the stage for her opening monologue, there was a tacit understanding that we were about to watch a wounded, possibly dying organization, carrying on as though nothing was wrong. This, while listening to a canonical masterwork specifically created to transform human grief into everlasting glory.

Chen was all smiles as she ascended the podium. Before lifting her baton she quoted Brahms’ inspirational response to the completion of his monumental masterwork: “Now I have surmounted obstacles I thought I could never overcome, and I feel like an eagle, soaring ever higher and higher.”

MSO by the Numbers

Average total number of employees 2009-11: 173

Average musician salary: $27,200

Highest musician salary: $29,000

Amount donated by chorus member Herbert Zeman after the crisis was announced: $100,000

Amount raised by the Symphony Chorus since the crisis was announced: $13,000

Amount raised by the Symphony League since the crisis was announced: $17,000

Amount MSO hopes to raise via Kickstarter: $25,000

Amount pledged on Kickstarter so far: $10,904

Projected shortfall for the 2013-14 Season: $400,000

Number of seats in the Cannon Center: 2,100

Number of Seats in the Duncan-Williams Performance Hall at GPAC: 824

General admission ticket to Handel’s “Messiah”: $25

Average yearly CEO income 2009-11: $127,770

Conductor/Music Director Mei-Ann Chen’s reportable compensation for 2011: $113,692

Revenue less expenses, 2008: -$1,731,985

Revenue less expenses, 2011: -$651,148

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks