Often a meme will circulate listing the hits of bygone times. A roll call of great releases in, say, 1977 will leave one feeling it was a golden age of recorded music, our contemporary sounds paling in comparison. Looking over this year’s best-of list, however, I’m inclined to think that 2024 will be celebrated in much the same way. And if you should beg to differ, I would only refer you to those wise wake up call offered by GloRilla herself, “Do y’all know what the f*ck goin’ on?? (goin’ on … goin’ on … goin’ on …)”

Aquarian Blood – Counting Backwards Again (Black & Wyatt)

This caps off a trilogy of sorts, over which the sometime punk screamers dialed it back into the acoustic realm. Meticulously crafted yet loose, these songs are dark, primitive missives haunted by trauma and desire, as if German sonic artists Can reinterpreted the Incredible String Band.

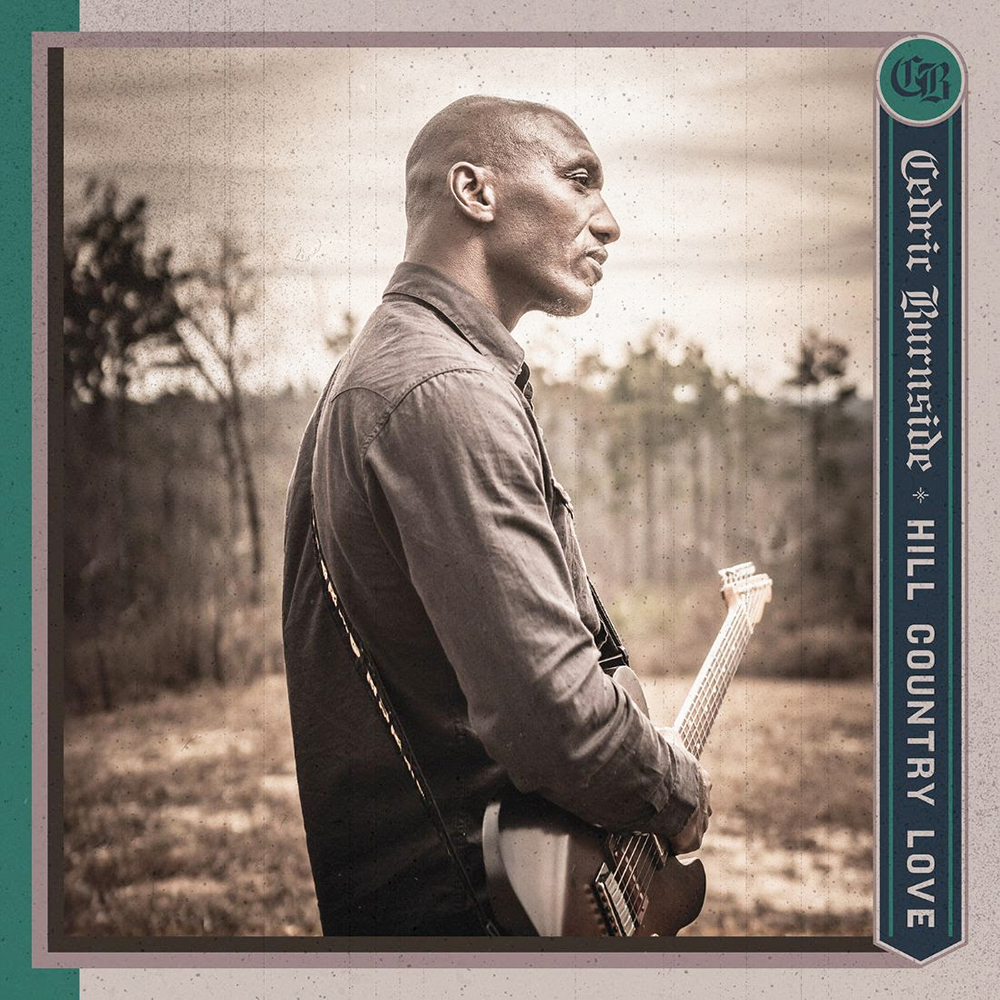

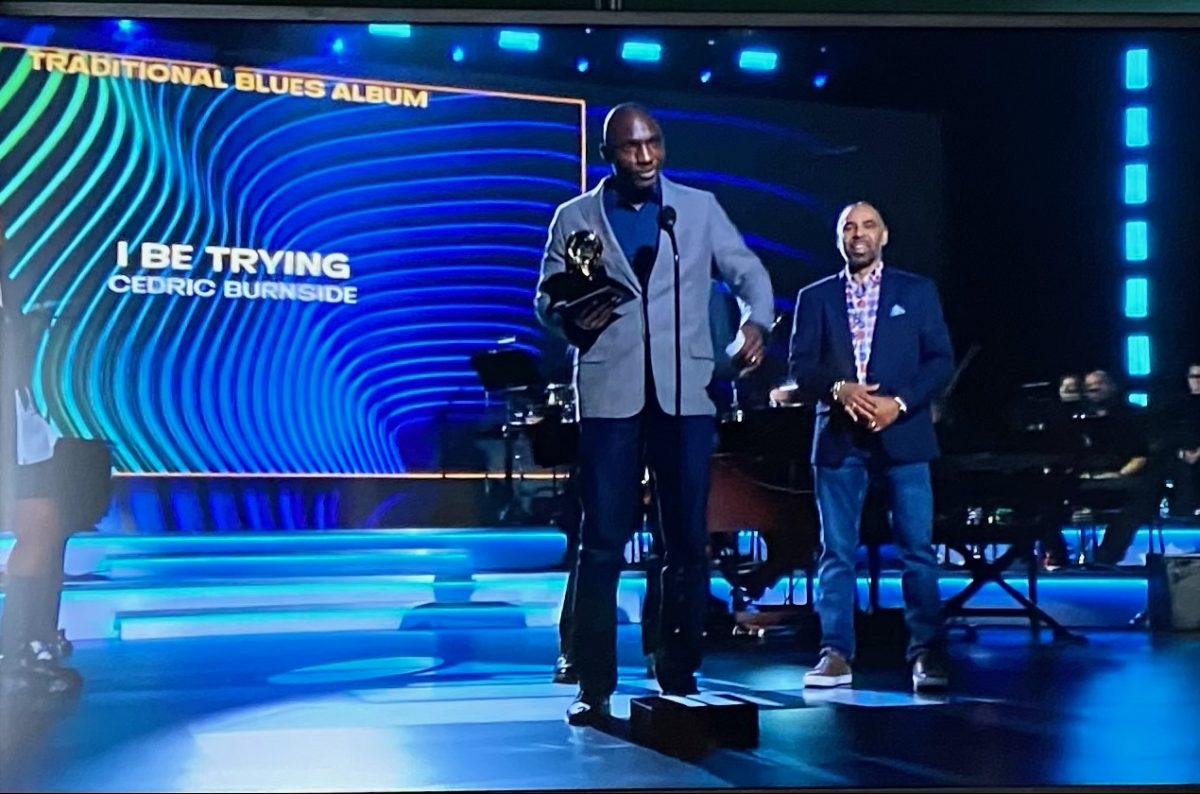

Cedric Burnside – Hill Country Love (Provogue)

Burnside’s latest album turns the volume up, yes, but not the distortion. Bringing more of a full-band sound, this particular Burnside eschews the hard rock guitar tones that were his grandfather R.L.’s trademark. There are echoes of 2021’s I Be Trying’s quieter soul-imbued originals (“Smile”), but funkier, staccato riffs predominate — at least until he breaks out the acoustic for traditional numbers.

GloRilla – Ehhthang Ehhthang and Glorious (CMG/Interscope)

Rolling Stone ranked October’s Glorious among the year’s best, but we in the city where “everything is everything” tapped into the Ehhthang Ehhthang mixtape way back in April. While the 2024 releases are two peas in a pod, Ehhthang was arguably more significant as Glo’s triumphant debut in the full-length format. And tracks like “No Bih” slay (in Latin, no less) in such a stark, Memphis way: “F*ck it, carpe diem/I make ‘em motivated (okay)/Grammy-nominated (okay), f*ck whoever hatin’.”

IMAKEMADBEATS – WANDS (UNAPOLOGETIC)

While there are mad beats throughout this instrumental journey, there are also orchestral passages both ethereal and bombastic, at times sounding eerily like the ’70s synth-meister Tomita. It’s an interstellar trip in audio form, in which you’re never sure if you’re hearing a sample or an intricate new composition by MAD himself. “I’m Losing My Mind I’m OK” even features lyrics, hauntingly sung by Tiffany Harmon.

Juicy J and Xavier Wulf – Memphis Zoo

While Juicy J co-founded the dark horror-hop of Three 6 Mafia, this collab with fellow Memphian Wulf is, paradoxically, dark, ominous, and … fun. But there’s a gravitas here, too, as on the most popular track, album opener “The Truth,” an exhortation to cut the BS, stop fronting, and face facts. And a deeper truth about our times comes out in personal fave “Alley Oop”: “We’re living in the era of the alley oop,” and it’s not a good thing.

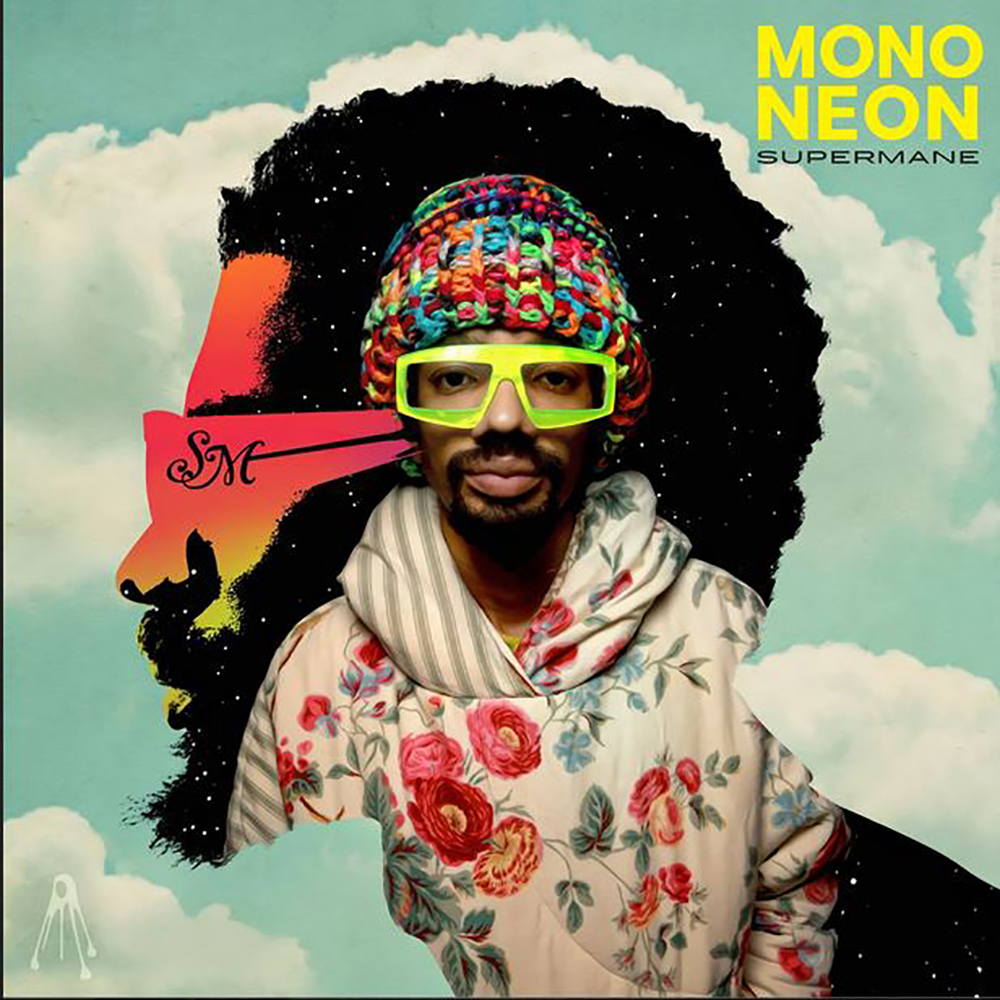

MonoNeon – Quilted Stereo (Court Square)

“I walked in the room and got butterflies.” So MonoNeon described his studio work with Mavis Staples on “Full Circle,” a highlight of Dywane “MonoNeon” Thomas Jr.’s latest work. With its doo-wop-ish vocal bass riff evoking a gospel bounce right out of the last century, it embodies funk and soul’s past, present, and future. Then there’s the sing-along jam with George Clinton, the perfectly Clinton-esque [and downright bluesy] “Quilted!” – an ode to flying your sartorial freak flag high, even if that means walking down the street decked out in bespoke, multicolored quilts. Then there’s the chugging New Wave pop of “Church of Your Heart,” the jungle beat rap of “Segreghetto,” and the sparkling sizzler of the summer, “Jelly Roll,” full of glossy synth warbles and bass stabs, its video overflowing with extras seemingly right out of the Crystal Palace roller-skating scene. MonoNeon’s greatest work yet.

NLE Choppa – SLUT SZN (Warner)

One of four releases by Choppa this year, all carry on his raunchy “Slut Me Out” variations, most audaciously with this album’s shuffling, acoustic guitar-driven “Slut Me Out 2 (Country Me Out),” featuring J.P., who sings, “If I was a cowgirl/I’d wanna ride me too!” Both versions skew gender in new ways for hip-hop, but it’s the stylistic mash up of the galloping, dancehall-flavored “Catalina” with Latin star Yaisel LM that truly takes Memphis hip-hop into global waters, reflecting Choppa’s Jamaican roots.

The Lisa Nobumoto Jazz Masters Orchestra – A Tribute to Jazz Singer Nancy Wilson

Having performed with the great Teddy Edwards for decades, this Memphian knows how to give Wilson’s catalog her own individual stamp. “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” becomes a ballad, worlds away from Frankie Valli’s stomper. “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” verges into boogaloo territory, yet with a relaxed delivery. Carl Wolfe’s big, brassy arrangements give the album a rare jazz classicism.

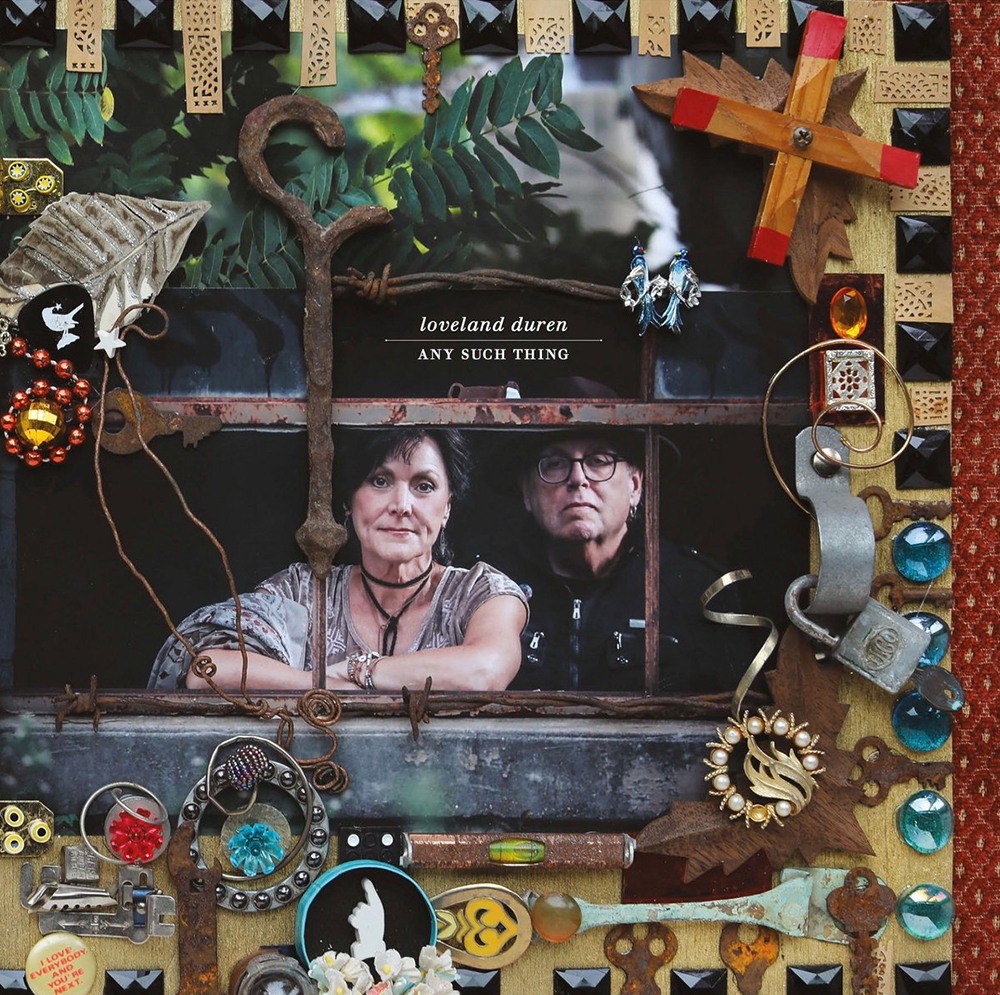

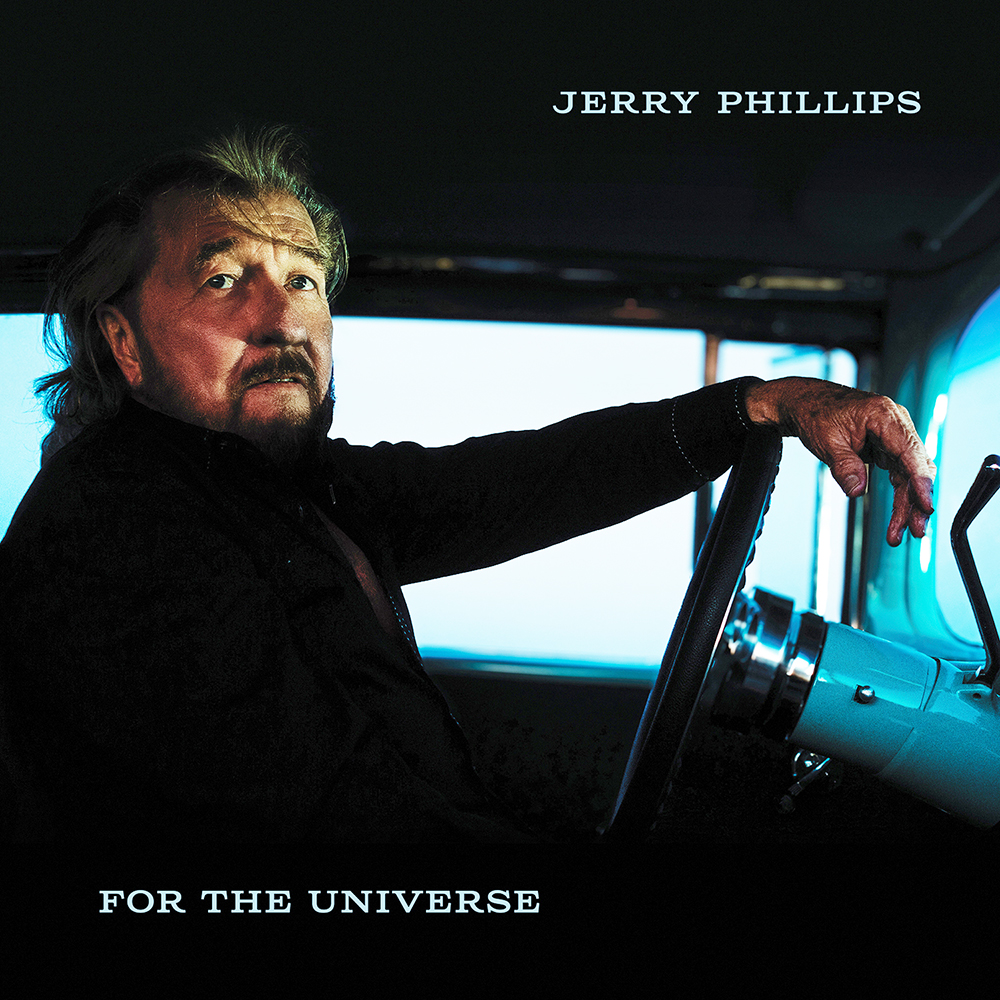

Jerry Phillips – For the Universe (Omnivore)

Though this is Phillips’ debut album, his decades of experience recording with great songwriters like John Prine at the studio his father built lend it the feel of a career-topper from the last century. The wry observations and hard-won wisdom of songs like “Specify” (exhorting his lover to say what she wants) or “She Let Me Slip Right Through Her Fingers” are carried by Phillips’ voice, echoing Charlie Rich or Johnny Rivers, and a band of ace Memphis session players.

Talibah Safiya – Black Magic

As artist-in-residence at the Rudi E. Scheidt School of Music last year, Safiya tapped into the High Water Recording Company’s back catalog, working with producer/engineer Ari Morris to weave generous helpings of Mississippi blues and soul into her samples. Erstwhile Memphian-turned-international-producer Brandon Deener lends his sonic touch as well, not to mention guitarist MadameFraankie, who brings a simmering soul vibe to underpin Safiya’s powerful-yet-playful voice.

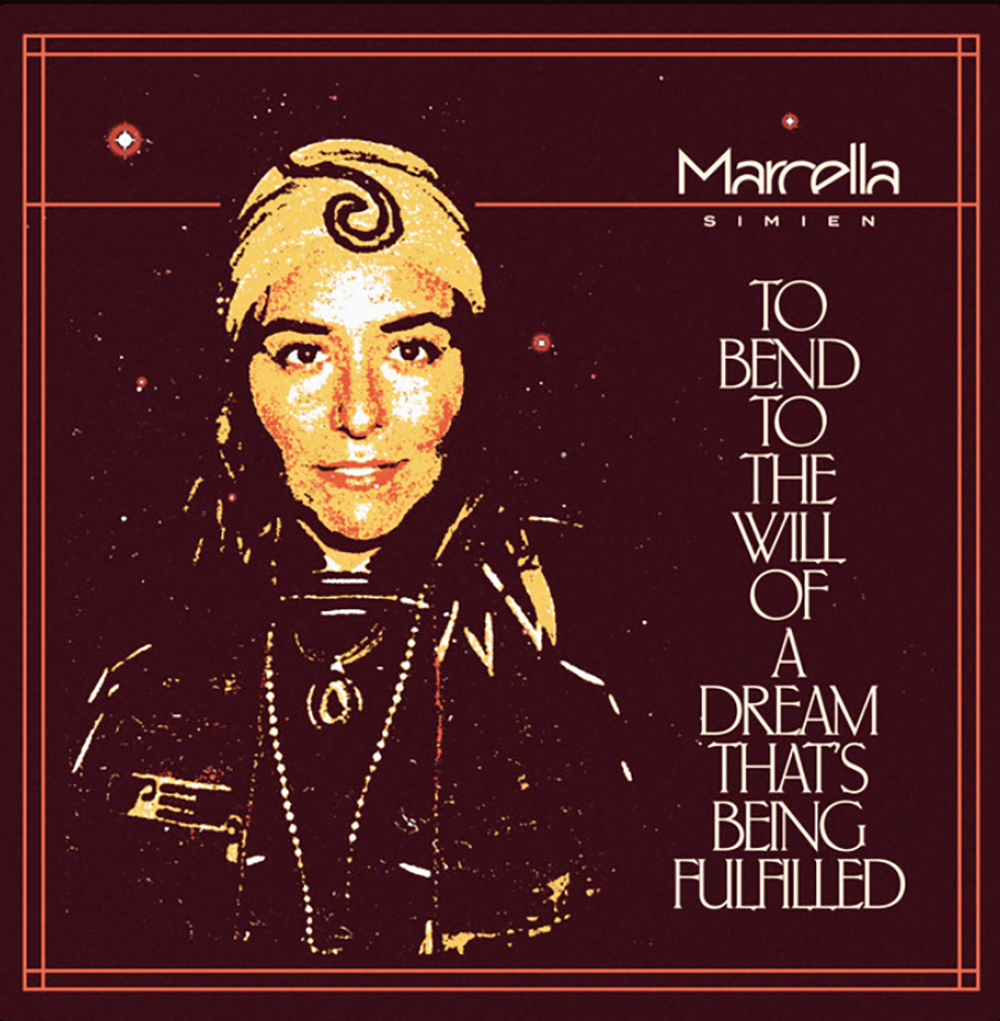

Marcella Simien – To Bend to the Will of a Dream That’s Being Fulfilled

For this most personal of journeys into her family’s past and her own well-being, Simien’s playing nearly all the instruments, crafting a setting in a kind of synthetic world-building, evoking the sweep of generations with the sweep of electronic filters. Rootsier sounds also make an appearance, as the artist conjures a timeless space to commune with her ancestors.

Snowglobe – The Fall

Like much of Snowglobe’s earlier output, this is rich with layers of ear candy. Though grounded by chords on an acoustic guitar or piano, the arrangements fill out with all manner of harmonies, synthesizers, or electric guitar riffs and hooks. Think Badfinger meets “Soul Finger,” with

hints of Harry Nilsson’s darker moods and post-‘90s quirks all their own.

Cyrena Wages – Vanity Project

Produced and mixed by Matt Ross-Spang, this album has some of the rootsy, vintage elements of his previous work with Margo Price, yet with the contemporary pop instincts once championed by one of Wages’ heroes, Amy Winehouse. Most of all, the sounds jump out of the speakers with the grit of a real band, which includes guitarist and songwriting collaborator Joe Restivo.

All albums self-released except where noted.