For a third straight year, many Tennessee students strived to climb back from academic and mental health challenges after COVID-19 forced them into remote learning.

But it was the unexpected events that dominated education news in Tennessee in 2023 and exposed new fault lines: A deadly shooting at a Nashville private school sparked protests and a backlash at the state Capitol. A superintendent search in the state’s largest school district unraveled just as it was about to wrap up. And the state ordered an 11th-hour overhaul of school accountability measures that will fall hardest on schools that serve students from low-income families.

Beyond that, some of the biggest headlines were about the ripple effects of Tennessee laws that put new pressure on public schools, including the rapid spread of private-school vouchers, the anxiety around high-stakes testing for third graders, and restrictions on what teachers can say in their classrooms about race and bias.

Chalkbeat Tennessee’s Marta W. Aldrich, our senior correspondent in Nashville, and Laura Testino, our Memphis-Shelby County Schools reporter, covered all those issues like honeysuckle covers the South. They connected with experts and advocates, sought out documents and data, and, most of all, showcased the voices of students, parents, and educators to bring you closer to the big stories driving education in the Volunteer State.

Here are some of the 2023 stories that resonated most with you — and with us.

Nashville students protest the state’s lax gun laws

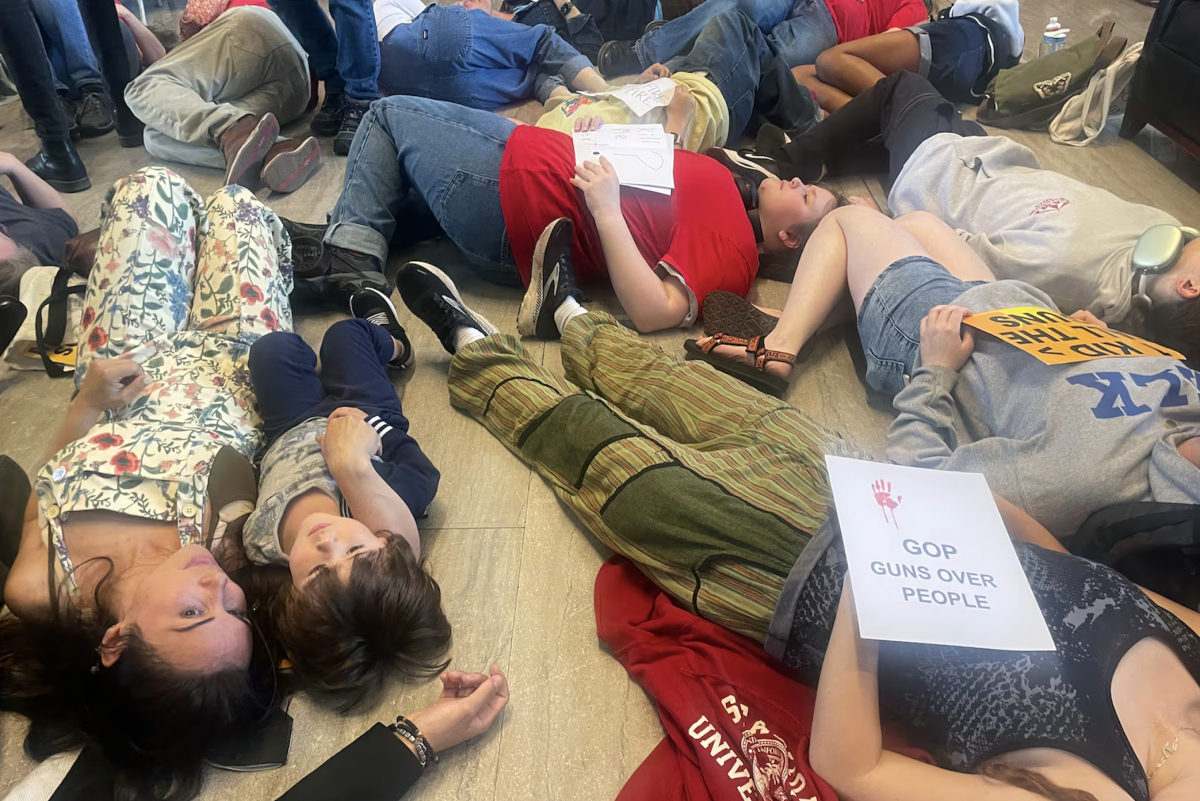

On March 27, an intruder armed with legally obtained, high-powered guns entered The Covenant School in Nashville and killed three adults and three 9-year-olds. The school was private, but the impact quickly spread to the public sphere when thousands of students and educators responded with days of protests against the state’s lax gun laws.

A story by Marta about the students protesting at the state Capitol in Nashville was the most-read story of 2023.

Among other things, it called attention to the disconnect between public support for tighter gun safety laws and a legislature that has moved in the other direction, eliminating many requirements for permits, safety training and waiting periods, and allowing purchases of some of the most deadly weapons.

Marta’s coverage that day showcased the voices — and faces — of the students who are coming of age in an era of escalating gun violence and turning their anger and anxiety into activism.

“We all want to live through high school,” said a 17-year-old student Marta spoke with, “and that’s why we’re here today.”

In her continuing coverage, Marta focused on how Tennessee lawmakers continued to push for broader access to guns, even as Nashville teachers were struggling to cope mentally and emotionally with the aftermath of the Covenant shooting.

A special legislative session on gun safety yielded no new restrictions, angering parents, students, and gun control activists.

“Today is a difficult day,” said David Teague, a father of two children at Covenant. “A tremendous opportunity to make our children safer and create brighter tomorrow’s has been missed. And I am saddened for all Tennesseans.”

Lawmaker expulsions: When a teachable moment becomes taboo

The gun safety protests roiled the state Capitol, culminating in the expulsion of two lawmakers who led the protests on the House floor. They also created confusion in Tennessee classrooms about how to discuss what happened.

In all, three Democratic lawmakers faced expulsion resolutions over their role in the protests, but only two of them — Justin Jones of Nashville and Justin Pearson of Memphis, both young Black men — were actually voted out by the GOP-dominated chamber. The House spared the third lawmaker, Gloria Johnson of Knoxville, who is a white woman.

The incident drew national attention, and scorn, as an example of racism and white privilege in the halls of power. But because of a state law that restricts teaching about race, many teachers struggled with how to answer students’ questions or engage them in conversations about it. While tracking the expulsion story, Marta and Laura also explored what happens when state policies collide with learning and engagement in the classroom, and what students lose when they do.

“I think these conversations would go much deeper if our teachers didn’t have the fear of these new laws hanging over them,” one high school senior in Nashville told them.

The same themes resurfaced in Laura’s coverage of a book event at Whitehaven H.S. in Memphis, featuring authors of “His Name Is George Floyd.”

Laura discovered a social media exchange that revealed how the authors faced restrictions on presenting their book to students because of concerns about the state laws governing library books and “age appropriate” materials. Tennessee’s laws restricting classroom discussions of race also loomed in the background.

Laura resolved to tell the story of how the restrictions came to be, and how they were communicated to the organizers of the book event and the authors. But the state law is a touchy subject for educators trying to steer clear of trouble, and Laura found it challenging to get the full story from the school district.

According to the authors of the book, journalists Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa, students at Whitehaven didn’t get the full story about George Floyd either. Samuels wrote an essay about the experience in The New Yorker.

Memphis superintendent search moves in fits and starts

It was just over a year ago that Memphis-Shelby County Schools announced an accelerated process for selecting a permanent successor to Joris Ray, who resigned in August 2022 amid charges that he abused his power and violated district policies.

But the superintendent post is still vacant, and the search continues.

What was supposed to be a grand unveiling of finalists in April devolved into an argument about process when some board members decided they didn’t like the slate of candidates selected by the search firm.

A big sticking point was the selection of the interim superintendent, Toni Williams, as a finalist. She had once pledged not to apply for the permanent post. And Chalkbeat Tennessee reported that the search firm, Hazard, Young, Attea & Associates, didn’t enforce board policies on minimum qualifications for the job in screening candidates.

Chalkbeat Tennessee has closely tracked the ensuing drama, including the resignation of the board’s vice chair, the banning of several activists from district property, and big questions about whether the public display of board dysfunction would repel top national candidates.

A rebooted search is now reaching its final stages, with a target of having the next superintendent on the job by summer. Whoever emerges as the leader will have a heavy workload: navigating tough budget decisions, coordinating a massive facilities overhaul, and driving academic recovery in a district where nearly 80% of students aren’t proficient in reading.

Accountability measures add to pressure on districts — and children

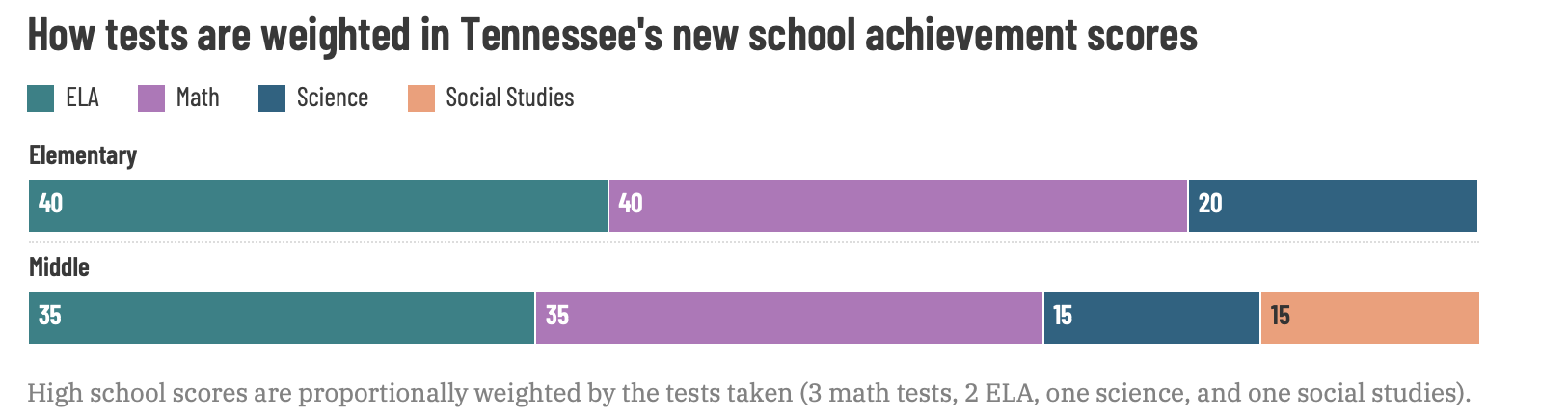

In a sign of continuing recovery from the pandemic, students’ proficiency rates in math and language arts improved in most districts across the state, according to results from the Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program, or TCAP test. The gains in Memphis-Shelby County schools were more muted than in past years.

Along with Thomas Wilburn, Chalkbeat’s senior data editor, Marta provided a comprehensive report on the results and a data tool to help readers look up how students in each district performed.

Beyond the scores, Chalkbeat’s coverage zeroed in on last year’s class of third-graders, and the outsized burden they carried. These students were kindergartners when the pandemic struck in March 2020, sent home to learn remotely just as their formal education was beginning.

Statewide, this was also the first cohort of third-graders who faced the threat of being held back if they couldn’t demonstrate proficiency on the TCAP language arts test. Statewide, about 60% of third-graders did not meet the standard for proficiency. In MSCS alone, more than 6,000 students missed the mark.

Laura focused on one of them: 8-year-old Kamryn, an anxious third-grader who chose to walk out of her school rather than face the results of a state test that could cause her to remain in the third grade.

“She told me that she was tired of school,” her mother told Laura.

Kamryn’s tale reflected the human toll of testing and accountability measures in a school district where children were, long before the disruption of COVID-19, already facing many challenges.

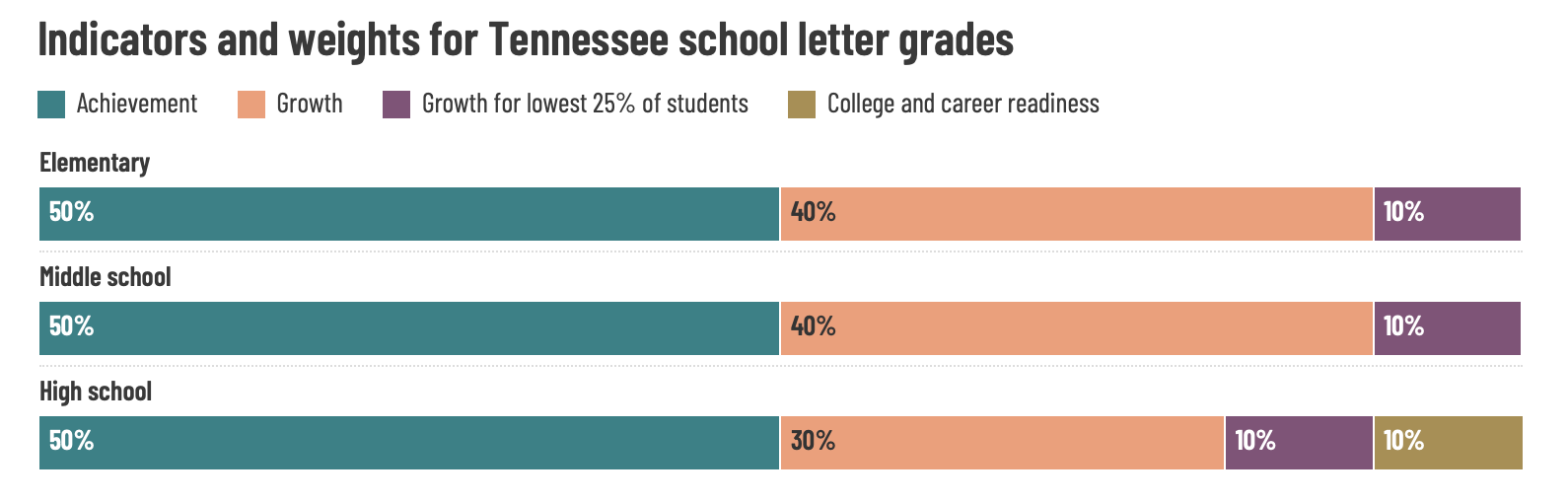

School district leaders and administrators now face another set of accountability pressures: the start of a new letter-grading system for all public schools, mandated by a 2016 state law.

They had been waiting for these A-F grades for years, thinking they understood what the criteria would be. But the state education department decided to change the criteria late this year to stress proficiency over growth, mostly ignoring the feedback it received from town halls and public comments. That means more schools in struggling areas are likely to receive D’s or F’s.

The grades are due out Thursday.

Laura and Marta’s coverage adds to the discourse of how Tennessee continues to apply new scrutiny to public schools with no guarantees of helping them to improve.

Tennessee legislature looks at rejecting billions of dollars in federal education funds

To many observers, it seemed like just political posturing when Tennessee House Speaker Cameron Sexton suggested that the state reject billions of dollars in federal education funds so it could free itself from federal regulations.

But Marta knew that such a potentially sweeping idea needed to be treated seriously, because Tennessee receives about $1.8 billion in federal aid — and because no state had ever rejected federal funding before.

She went to work on a Q&A for readers to show what giving up federal funds would mean for families and the state’s most vulnerable students. In particular, Marta noted, without the conditions that come with federal funding, there’s no guarantee that Tennessee law would work as well as federal laws designed to protect students with disabilities.

Sure enough, Sexton was serious enough about his suggestion to order a full-blown legislative study, with hearings featuring testimony from school district leaders and conservative think tanks — but not parents.

The panel considering the idea is still doing its research, but its co-chair says it’s unlikely the state will follow through.

Tennessee governor proposes to make private-school vouchers available to all

One by one, obstacles to Gov. Bill Lee’s private-school voucher program have fallen away.

A program once billed as a pilot project for two counties has expanded to a third under a law passed this year. And Lee now wants to make it universal, available to all students statewide.

Marta’s coverage of the proposal delivered needed context about Lee’s continuing effort to persuade more parents to sign on to the program, which has attracted only about 2,000 students so far, well below capacity.

The story also looks ahead to the obstacles Lee will face in getting his bill through the legislature. Already, leaders of many rural and suburban school districts have announced their opposition to the bill based on the same concern that urban districts have: that it will divert more money away from public schools.

It’s a story that we’ll be following closely when the legislature convenes next month and the full language of the bill becomes available. Stay tuned.

Bureau Chief Tonyaa Weathersbee oversees Chalkbeat Tennessee’s education coverage. Reach her at tweathersbee@chalkbeat.org.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.